Chapter 26 Dehydration/Fluids and Electrolytes

ETIOLOGY

What Causes Dehydration and Electrolyte Imbalance?

Dehydration most commonly develops when diarrhea and/or vomiting cause excessive water and electrolyte loss. It may also develop from inadequate fluid intake or from other causes of excessive water and electrolyte loss (see Chapters 28, 33, 41, and 60). Severe dehydration can cause hypovolemic shock if fluid loss compromises the circulatory system. Disturbances of water and electrolyte balance may develop without dehydration, such as severe hyponatremia caused by excessive water intake (“water poisoning”) and severe hypernatremia caused by excess sodium intake. Disturbances of acid/base balance may also accompany fluid and electrolyte disorders and are common in diabetic ketoacidosis.

What Are the Basics of Fluid and Electrolyte Management?

The total daily fluid requirement is the sum of maintenance + deficit + ongoing losses.

Maintenance fluids are required daily to replace physiologic fluid and electrolytes losses (Table 26-1). Holliday and Segar demonstrated that daily water and electrolyte needs depend on metabolic rate, which is highest in infants and young children. The healthy child’s maintenance fluids are provided orally. Maintenance needs are increased by several mechanisms, including fever. A fluid deficit may result if adequate maintenance is not provided.

Table 26-1 Physiologic Fluid Losses

| Fluid Loss | Component (% Maintenance) | |

|---|---|---|

| Sensible fluid loss (55%) | Urine (50%) | Stool (5%) |

| Insensible fluid loss (45%) | Skin (30%) | Lungs (15%) |

EVALUATION

How Do I Determine Maintenance Fluid Needs?

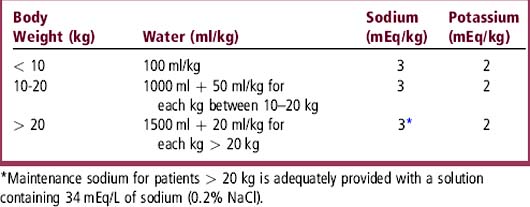

Calculation of maintenance based on body weight most often suffices beyond the newborn period (> 28 days of age) (Table 26-2). In this formulation adapted from Holliday and Segar’s work, age and weight reflect metabolic rate.

Does the Physical Examination Detect Dehydration?

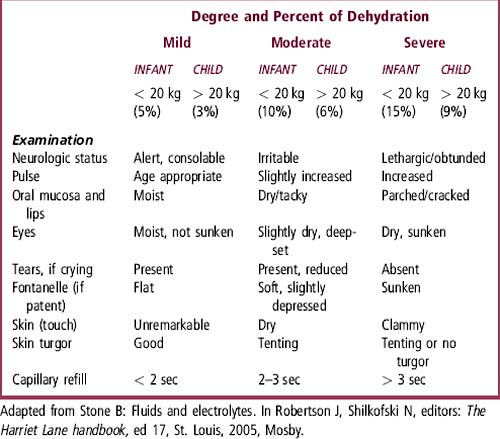

Acute water loss in a dehydrating illness results in an acute weight loss, but the amount of water lost is not exactly the same as the weight loss. For purposes of calculation, the three categories of dehydration are assigned percent values to estimate water loss. For infants less than 20 kg, dehydration is classified as mild (5%), moderate (10%), or severe (15%). An estimate of the severity of dehydration is based on physical findings (Table 26-3). In mild dehydration, physical evidence is usually lacking (or at most minimal). As dehydration worsens, physical findings become more obvious. Capillary refill is the most reliable and reproducible marker of hydration status.

TREATMENT

What Are the Steps to Treat Severe Dehydration?

Identify shock and administer emergency isotonic fluid. This supports the circulation and corrects hypovolemic shock. Frequent reassessment of response to therapy is needed.

Identify shock and administer emergency isotonic fluid. This supports the circulation and corrects hypovolemic shock. Frequent reassessment of response to therapy is needed.

Determine the nature of dehydration (isonatremic, hyponatremic, hypernatremic) based on electrolytes.

Determine the nature of dehydration (isonatremic, hyponatremic, hypernatremic) based on electrolytes.

Calculate water and sodium deficits.

Calculate water and sodium deficits.

Correct water and electrolyte deficit and provide for maintenance.

Correct water and electrolyte deficit and provide for maintenance.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree