I. Predominantly large vessel vasculitis

Takayasu arteritis

II. Predominantly medium-sized vessel vasculitis

Kawasaki disease

Childhood polyarteritis nodosa

Cutaneous polyarteritis

III. Predominantly small vessel vasculitis

A. Granulomatous

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA), formerly known as Wegener’s granulomatosis

Churg–Strauss syndrome

B. Nongranulomatous

Microscopic polyangiitis

Henoch–Schönlein purpura

Isolated cutaneous leukocytoclastic vasculitis

Hypocomplementemic urticarial vasculitis

IV. Other vasculitides

Behçet’s disease

Vasculitis secondary to infection (including hepatitis B-associated polyarteritis nodosa), malignancies, and drugs (including hypersensitivity vasculitis)

Vasculitis associated with systemic connective tissue diseases

Isolated vasculitis of the central nervous system

Cogan syndrome

Unclassified

Clinical presentation of the most common childhood vasculitides usually develops abruptly, and diagnostic characteristics become apparent in a few days. In some less common vasculitides, various signs and symptoms may develop over weeks or months. Establishing the diagnosis of vasculitis requires a high index of suspicion and is often difficult and delayed. Clinical features such as fever, weight loss, fatigue of unknown origin, various skin lesions (palpable purpura, vasculitic urticaria, livedo reticularis, nodules, ulcers), neurological manifestations (headache, focal neurological signs), pain or inflammation of joints and muscles, serositis, hypertension, pulmonary infiltrates or hemorrhage together with laboratory features of increased inflammatory markers [erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein (CRP), leukocytosis], anemia, eosinophilia, hematuria, elevated factor VIII–related antigen (von Willebrand factor), presence of antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA), circulating immune complexes, and cryoglobulins suggest a possible diagnosis. A definitive diagnosis often requires additional vessel imaging, such as magnetic resonance angiography or conventional angiography, and frequently biopsy of one or more sites.

Besides difficulties in establishing a diagnosis, assessment of vasculitic disease activity is often challenging and the outcome of some vasculitides may be serious or fatal [2–4]. Various forms of vasculitis account for 1–6 % of pediatric rheumatic diseases, but the true incidence and prevalence are unknown. The two most common childhood vasculitides, accounting for 60–80 % of all types of vasculitis, are Henoch–Schönlein purpura (HSP) and Kawasaki disease (KD). All other forms of vasculitis are uncommon – Takayasu arteritis (TA), polyarteritis nodosa (PAN) – or rare – granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA), central nervous system (CNS) vasculitis. There are, however, large geographical differences in relative disease frequency, with KD and TA being more prevalent in Japan and PAN more common in Turkey [2, 4, 5]. Several aspects of corticosteroid therapy in the most common childhood vasculitides are presented in this chapter.

Henoch–Schönlein Purpura

HSP is the most common childhood vasculitis. It is a systemic vasculitis with multiorgan involvement and presents with palpable purpura, arthritis or arthralgia, abdominal pain, with the possible addition of gastrointestinal hemorrhage and renal disease. The presence of purpura is a compulsory criterion for the diagnosis, other signs or symptoms are present more variably. Other organs can also be involved including central nervous system vasculitis with seizures, coma, hemorrhage, Guillain–Barré syndrome, central and peripheral neuropathy, as well as involvement of the respiratory system with recurrent epistaxis, pulmonary hemorrhages, interstitial pneumonitis, parotitis, carditis, and stenosing urethritis. In boys the most frequent additional manifestation is scrotal pain and swelling [6–8].

The reported incidence of HSP varies between 10 and 30 cases per 100,000 children with an equal incidence in male and female patients. Most cases present in children younger than 10 years of age with mean age of presentation at 6 years. It occurs predominantly in the cold months of the year, often preceded by an upper respiratory tract infection. This suggests a potential infectious trigger and multiple case reports describe an association with various respiratory pathogens, most commonly with streptococcus, staphylococcus, and parainfluenza [2, 6–8].

The characteristic pathological feature of HSP vasculitis is a deposition of IgA antibodies – containing immune complexes in the vessel walls of the affected organs and kidney mesangium. Abnormal glycosylation of immunoglobulin A1 molecules predispose patients with HSP to form large immune complexes with impaired clearance. They are deposited in small vessel walls of the affected organs and in the kidney mesangium and trigger immune response with inflammatory reaction.

Clinical Manifestations

Cutaneous Involvement

Skin involvement is essential for the diagnosis to be made. The most common manifestations are palpable purpura and petechiae, but other forms of skin involvement like erythematous, macular, urticarial, and bullous rashes have been observed. Skin involvement is usually distributed symmetrically most prominently over the extensor surfaces of the lower limbs, buttocks, and forearms – on pressure-bearing surfaces (Figs. 1 and 2). Changes on the trunk and face are occasionally described in younger children with edema over the dorsa of the hands and feet as well as around the eyes and forehead. In 25–30 % of children with HSP, recurrence of purpura is observed.

Fig. 1

Hemorrhagic necrotic skin lesions in a patient with Henoch–Schönlein purpura

Fig. 2

Penile involvement in a patient with Henoch–Schönlein purpura

Arthritis

Three quarters of children with HSP have arthritis or arthralgia. The most commonly affected joints are the large joints of the lower extremities. There is marked periarticular swelling and tenderness, usually without erythema, warmth, and effusion. The joint disease is transient and resolves within a few days to 1 week without chronic damage.

Gastrointestinal Manifestations

Edemas and submucosal and intramural hemorrhage due to vasculitis of the bowel wall cause diffuse abdominal pain in approximately two thirds of children with HSP. The proximal small bowel is most commonly affected. Symptoms usually appear within 1 week after onset of the rash, but in up to one third of cases they may precede other manifestations. The most common severe gastrointestinal complication is intussusception, which occurs in 3–4 % of patients. It presents with severe, often colicky abdominal pain and vomiting. Other severe, although less common gastrointestinal complications, include gangrene of the bowel, bowel perforation, massive hemorrhage, acute pancreatitis, enteritis, and hepatobiliary involvement.

Renal Disease

Renal involvement with glomerulonephritis is reported in approximately one third of children with HSP. It usually presents with isolated microscopic hematuria; there might be a variable degree of proteinuria with normal renal function. In less than 10 % of cases it may be a serious, potentially life-threatening complication with acute nephritic syndrome with hypertension and renal failure. It seldom precedes the onset of rash and usually develops within 4 weeks after disease onset. The extent of the disease can be determined in the initial 3 months, and in a few children nephritis can occur much later in the course, sometimes after numerous cutaneous recurrences.

Treatment

The use of glucocorticosteroids (GCs) in HSP has been a source of controversy and debate [9–13]. In the majority of cases, management of HSP includes supportive care with maintenance of good hydration, nutrition, electrolyte balance, and control of pain and hypertension. Although GCs have a dramatic influence on decreasing the severity of joint and cutaneous involvement of the disease they are usually not indicated for management of these manifestations. The evidence of using early GC treatment to shorten duration of abdominal pain and to decrease the risk of intussusception and surgical intervention is based only on case reports and small studies and is not strong enough to recommend it to all patients with HSP and abdominal involvement, since the majority of patients improve spontaneously [14]. GCs are generally used for patients with HSP and severe abdominal pain and hemorrhage, with prompt symptomatic improvement. Ronkainen et al. reported reduced abdominal and joint pain with prednisone of 1 mg/kg/day for 2 weeks, with weaning over the subsequent 2 weeks [15]. However, studies have not demonstrated a clear advantage of prednisolone over supportive therapy.

Short-term GC therapy is effective in the management of pain in severe orchitis. In pulmonary hemorrhage, which is a rare but potentially fatal complication of HSP, aggressive immunosuppressive treatment with a combination of intravenous methylprednisolone pulses and other immunosuppressive agents is used.

A recent Cochrane Review and other long-term studies showed there is no evidence from randomized controlled studies that the use of GCs can prevent kidney disease in children with HSP or change the long-term prognosis of renal involvement [16]. Urine and blood pressure abnormalities 8 years after HSP are associated with nephritis at its onset. However, prednisone can be effective in treating renal symptoms: 61 % of renal symptoms resolve in patients treated with prednisone, compared with 34 % of patients treated with placebo [17]. Mild renal involvement with microscopic hematuria or mild proteinuria does not require immunosuppressive treatment, but these patients need close follow-up. GCs are still the main therapy for rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis or nephrotic syndrome, which is usually accompanied by crescents on kidney biopsy. Although the quality of evidence is low, pulse intravenous methylprednisolone followed by a 3–6-month course of oral steroids with the addition of cyclophosphamide or cyclosporine A is used. Additional treatment in small studies included intravenous immunoglobulins, plasmapheresis, and anti-clotting therapy [5, 9–13, 15, 18, 19].

Prognosis

In two thirds of children, disease is self-limiting with excellent spontaneous resolution of symptoms and signs. HSP recurs spontaneously or with repeated respiratory tract infections in one third of children usually in the first 6 weeks. Recurrent episodes are usually shorter and milder than the preceding one.

In the short term, morbidity and mortality are associated with gastrointestinal tract lesions or central nervous system vasculitis. The long-term morbidity of HSP is related to the degree of HSP nephritis. Overall, less than 5 % of children with HSP progress to end-stage renal failure. Poor prognostic factors are development of a major indication of renal disease within the first 6 months of disease onset, occurrence of numerous exacerbations, renal failure at onset, hypertension, or increased number of glomeruli with crescents on renal biopsy [2, 4, 6–9].

Kawasaki Disease

KD is the second most common vasculitis in childhood. It is an acute self-limiting vasculitis of unknown origin with clinical signs of prolonged fever, polymorphous rash, nonexudative conjunctivitis, mucosal changes, cervical lymphadenopathy, and erythema or desquamation of the extremities. Untreated KD can have severe complications and significant morbidity or even mortality. It can progress in 25 % of cases to cause coronary artery abnormalities, such as dilatation and ectasia; 2–3 % of untreated patients die as a result of coronary vasculitis. KD is a leading cause of acquired cardiovascular disease in children and is potentially an important cause of long-term cardiac disease in adult life. Since adequate and timely therapy can largely prevent these complications, early and accurate diagnosis is of great importance.

The disease has a higher incidence in Asian populations with a male predominance; there is marked seasonality with heightened incidence in winter and early spring in temperate climates. The majority (85 %) of children with KD are younger than 5 years.

The exact mechanisms of the disease are still unresolved nearly 50 years after it was described by Kawasaki in 1967. KD may result from an exposure of a genetically predisposed individual to a possible infectious environmental trigger. Up to 33 % of patients with KD have at least one concurrent infection at the time of diagnosis, but no correlation between a specific agent and the severity of the disease course has been identified [20, 21].

Clinical Manifestations

The diagnosis of KD is based on clinical criteria (Table 2) established by the Japanese Ministry of Health and adopted by the American Heart Association. If less than four of the principal features are present but two-dimensional echocardiography detects coronary artery abnormalities, patients are diagnosed with incomplete KD. Frequently, features of KD develop sequentially rather than simultaneously, which might result in misdiagnosis and treatment delay. In addition to the principal clinical findings, several other symptoms can be present, such as extreme irritability, arthritis, rhinorrhea, weakness, hydrops of the gallbladder, and mild anterior uveitis.

Fever (>39 °C) for at least 5 days | |

AND at least four of the following five diagnostic features | |

Polymorphous exanthema | |

Bilateral bulbar conjunctival injection without exudate | |

Changes in lips and oral cavity | Erythema, fissured cracked lips, strawberry tongue, or diffuse injection of oral and pharyngeal mucosae |

Cervical lymphadenopathy | (>1.5 cm diameter), usually unilateral |

Changes in extremities | Acute: erythema of palms and soles; edema of hands and feet |

Subacute: periungual peeling of fingers and toes (in the second and third week) | |

WITH exclusion of other diseases with similar clinical features |

The clinical diagnosis can further be hindered in a subset of patients, mostly younger than 12 months of age or older than 5 years, with less than four of the principal features but with laboratory results or echocardiographic evidence that suggest the diagnosis of KD. These patients present with incomplete KD.

The variability in patient presentation should encourage clinicians to consider KD in any case of prolonged and unexplained fever.

Additional supplementary laboratory criteria can aid in establishing the correct diagnosis: decreased levels of albumin (<3 g/dl); increased C-reactive protein; increased erythrocyte sedimentation rate >40 mm/h; elevated alanine aminotransferase; leukocytosis >15,000/mm; normochromic, normocytic anemia for age; and sterile pyuria >10 white blood cells/mm3.

The differential diagnosis of KD includes (1) various infections such as Epstein–Barr virus, adenovirus, echovirus, measles, toxic shock syndrome, scarlet fever, Rocky Mountain spotted fever, leptospirosis; (2) autoimmune diseases such as systemic-onset juvenile idiopathic arthritis or polyarteritis nodosa; and (3) juvenile mercury poisoning and adverse drug reactions including Stevens–Johnson disease.

The clinical course of the disease consists of four phases. In the acute phase, which lasts 1–2 weeks if untreated, children have a high spiking fever and principal symptomatic features. At this time, they may present with cardiac manifestation including valvulitis, pericarditis, and myocarditis. In the following subacute phase, children are at greatest risk of sudden death due to myocardial infarction. The subacute phase lasts approximately 2 weeks and is characterized by resolution of the fever. The third phase is the convalescent phase after cessation of symptoms and continues until acute-phase inflammatory markers return to normal serum levels. In the fourth, chronic phase, patients with coronary artery involvement require follow-up management (Figs. 3 and 4).

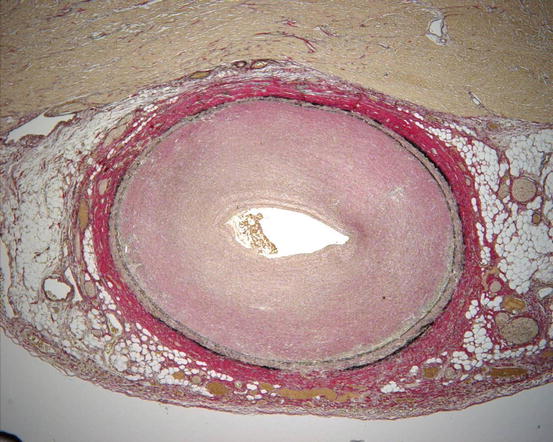

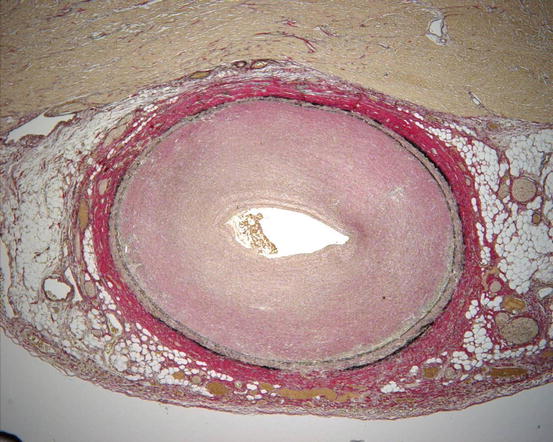

Fig. 3

Coronary artery vasculitis in a child with treatment-resistant Kawasaki disease and ischemic cardiomyopathy

Fig. 4

Histological changes in coronary artery vasculitis in treatment-resistent Kawasaki disease

Treatment

The aim of acute-phase management in KD is to reduce inflammation, particularly inflammation in the coronary arteries and myocardium. Early treatment, before day 10 of the disease, with a single dose of intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) over 12 h at a dosage of 2 g/kg has been shown to greatly reduce the risk of coronary artery lesions. In addition to IVIG, high “anti-inflammatory” doses of acetylsalicylic acid (ASA) of 80–100 mg/kg/day in divided doses in the United States and of 30–50 mg/kg/day in divided doses in the United Kingdom and Japan are used in the acute phase. The dose of ASA is lowered to an “antiplatelet” dose (3–5 mg/kg/day) following defervescence. ASA is continued until inflammatory markers have returned to normal and there is no evidence of coronary artery lesions. However, a Cochrane Review concluded there is insufficient evidence in support of using ASA in the acute phase for coronary artery prevention [23].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree