19 Coping and Stress Tolerance Mental Health and Illness

Mental Health Influences

Mental Health Influences

Neurobiological Context

Early mental health influences include the child’s genetic composition and the intrauterine environment’s effects on the developing fetus. Maternal nutrition, especially B12 and folic acid intake, and stress hormone levels are among the most documented influences on the structure and function of the evolving central nervous system (Beydoun and Saftlas, 2008). Severe prenatal nutritional deficiency is associated with the development of schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorders and congenital central nervous system abnormalities (Tottenham et al, 2010). Genetic disorders with behavioral components, like Prader-Willi, are more common in children born through in vitro technologies, raising the concern that suboptimal embryonic nutrition can alter brain development and differentiation (Stufferin-Roberts et al, 2008).

Mental Health in Primary Care

Mental Health in Primary Care

• Established therapeutic relationships with children and families

• Capacity to engage in mental health promotion and anticipatory guidance

• Familiarity with normal child development and healthy parenting

• Experience coordinating care with other health care specialists

• Familiarity with chronic care principles and practice improvement (Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health and Task Force on Mental Health, 2009; NAPNAP, 2007).

Prevention

Primary Prevention

• Responsive, thoughtful caregivers

• Parental recognition of individual achievements, efforts, and improvements

• High-quality preschool, elementary, and secondary schools

• Sense of control over one’s life

• Sense of one’s purpose, and clear self-identity

• Opportunities to interact with positive peers and adults

• Freedom from racism, sexism, discrimination, and poverty (Foy et al, 2010)

Healthy parenting strategies result in parents who are positive in tone and regard for the child, responsive to the child’s autonomy and individuality, neutral in response to unwanted behavior, and attentive to the child’s needs (Box 19-1 and see Chapters 4 and 16). Parents who have not experienced this type of nurturing often need education and coaching in positive parenting behaviors from a pediatric provider (McDonough, 2005).

BOX 19-1 Positive Parenting Strategies

Attend to the Child Individually

Allow the child to make reasonable choices.

Respond to child’s bids for attention with eye contact, smiles, and physical contact.

Comment on child’s appropriate and desirable behavior frequently and positively throughout the day.

Provide guaranteed special time daily: no interruptions, no directions, no interrogations.

Listen Actively

Paraphrase or describe what the child is saying.

Share the child’s affect by matching the child’s body posture and tone of voice.

Avoid giving commands, judging, or editorializing.

Convey Positive Regard

Communicate positive feelings (e.g., love) directly.

Give directions positively, firmly, and specifically.

Provide notice before requiring the child to change activities.

Label the behavior, not the child.

Praise competency and compliance; say thank you.

Avoid shaming or belittling the child.

Secondary Prevention

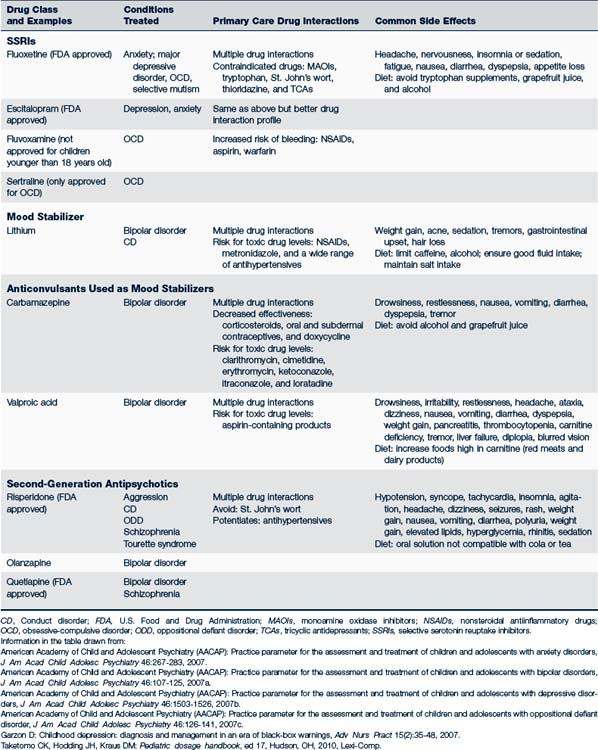

Use of medication to treat mental health problems in children is increasing, but there are concerns about pharmacological interventions of which primary providers must be aware. There are few randomized control trials involving children that demonstrate pharmacotherapeutic safety and efficacy. Existing research shows that medications that are effective in the management of adult mental health conditions are less effective or may be completely ineffective in children with similar diagnoses, likely due to differences in the organization and function of the developing brain of children at different ages. Many drugs used to treat mental health conditions have serious adverse side effects and require ongoing physiological monitoring (Table 19-1). Primary care providers assess for interactions between medications used in treating mental health conditions and commonly prescribed medications also used in primary care, such as antibiotics and contraceptives, which may result in impaired drug effectiveness or toxic side effects.

Tertiary Prevention

Tertiary prevention and intervention address major losses and trauma (e.g., victimization through sexual or physical abuse, parental marital problems, divorce, substance abuse, and parental psychopathological conditions). Even in the absence of behavioral manifestations of distress, a referral to a mental health specialist for further assessment and intervention is suggested because of the short- and long-term problems that result from traumatic experiences. In these cases, parents may not understand the need for referral. It is most helpful for the pediatric provider to frame the behavior problem as a “normal response to an unusual or stressful situation” with the goal of referral being to maximize the child’s development and growth. A release of information allows direct contact with the consultant to ensure follow-through. Ongoing follow-up is essential with children, families, and other professional providers.

Temperament Influences on Mental Health

Temperament Influences on Mental Health

Temperament is a foundation for coping. Temperament involves an individual’s characteristic style of emotional and behavioral response across situations and has generally come to be accepted as inborn. Although biological in origin, temperament characteristics evolve and develop over time and are influenced by and patterned in significant ways by the social environment. This view of temperament is clinically important because both short- and long-term psychosocial adjustments are shaped by the goodness-of-fit between the individual’s temperament and the social environment. (Goodness-of-fit refers to the congruence of a child’s temperament with the expectations, demands, and opportunities of the social environment, including those of parents, family, and daycare or school setting.) (See Table 4-2 for information about temperament types.)

Temperament Management

The goal for the primary care provider is to help parents achieve goodness-of-fit for their children. Specific strategies for intervening with temperament issues have been developed for parents (Table 19-2). Those who care for children (e.g., parents, teachers, other caregivers) should:

• Recognize the child’s innate behavioral qualities as expressions of temperament. This recognition can be facilitated by interview about child responses (e.g., changes in activities, new situations, changes in routines, new people) or by completing a standard temperament questionnaire.

• Understand how temperament is related to behavior and is not amenable to change. Allow parents to express their feelings about their child or their child’s behavior and assisting them to reframe their assessment more positively. Members of the extended family who often advise parents may need to be included to help alleviate parental feelings of failure.

• Develop temperament-based management strategies, especially ways to deal with the more challenging areas of temperament. Such strategies can be applied to new situations as the child develops and becomes more autonomous, including those that occur in toddlerhood and preschool, such as mealtime and bedtime, or during school-related activities, such as doing homework.

TABLE 19-2 Strategies to Help Parenting of Children With Different Temperaments

| Temperament Characteristic | Strategy |

|---|---|

| Activity | Recognize the child’s activity level and plan high-energy activities (such as long walks, family outings) with naps and child’s energy levels in mind. Plan for activities to keep high-energy children busy in situations when quiet is required (such as during religious services). |

| Rhythmicity | Take the child’s normal sleep, wake, and feeding schedule in mind when planning activities and outings. Avoid activities during “normal” naptimes. Use normal elimination patterns as a guide during toilet training. |

| Approach or withdrawal | Help teach young children skills to deal with discomfort felt while meeting new people or having new experiences. Provide opportunities for children with approach/withdrawal problems to experience new situations and to meet new people in a supporting and loving environment. Recognize that new situations may be stressful. |

| Adaptability | Teach young children how to deal with disappointment. Provide reassurance when things don’t go as planned. |

| Threshold of response | Recognize that not all children require the same amount of stimulation for calming. Adapt redirection strategies to the child’s personal response threshold. Modify approaches to the situation, i.e., serious situations require a more firm approach (e.g., when the child is in danger) and use care to not overrespond to more mild situations (e.g., when juice spills or things break). |

| Intensity of reaction | Help children to recognize their responses to positive and negative emotions. When an overresponse occurs, teach children how to modify their behavioral response to their feelings. Do not avoid situations in which frustrations may occur; part of developing emotional maturity is experiential. |

| Quality of mood | Use positive reinforcement for good mood responses to situations. Ignore negative mood responses. |

| Distractibility and attention span/persistence | Take a child’s development and distractibility into consideration when doing tasks that require concentration (i.e., homework, quiet time). Teach the child strategies to help stay on track. Help parents set realistic expectations of the child’s attention span. |

Assessment and Management of Mental Health Disorders

Assessment and Management of Mental Health Disorders

Assessment

Approaches to Children of Different Ages

Adolescents

• “Tell me about some of the things you do very well. What types of things do you have a hard time doing?”

• “You look very sad to me. Would you share with me what is making you sad?”

• “Many children have things they worry about. What worries you most?”

• “How are things going in your family?”

• “How are your relationships with other people? Do you feel like other people understand you and see you for who you really are?”

• “Everyone feels angry at times. What makes you angry? What do you do when you are angry?”

• “If you could change one thing in your life, what would it be?”

• “Tell me what you think the problem is from your point of view.”

History

The Symptom Analysis: Behavioral Manifestations

Parents are keen observers of their children, so it is wise to listen carefully to their observations and concerns. Behaviors that concern a parent may include those that are developmentally normal for the child, or they may represent extremes of the range of normal behavior. By obtaining a clear idea of the parent’s concerns, the provider can assess the parent’s level of knowledge about child development and behavior, clarify which behaviors are developmentally normal (but distressing to the parent), and confirm which behaviors fall outside the range of normal. Eliciting information from teachers and other caregivers reinforces parental reports and provides a contextual understanding of child behavior.

Family Domain: Common Family-Related Stressors

Common stressors that should be identified through the history are discussed in this section. Questions and specific examples of stressors are found in Table 19-3.

• Recent Changes. When inquiring about recent changes in the child’s life, it is helpful to specifically ask about changes in the family, work, school, and other settings because parents may not perceive some changes as sources of stress for their child. For example, parents may welcome a job promotion that includes the need for travel and a significant pay increase. However, this same change may stress the child, who is old enough to worry about how life will change with a traveling parent. Most recognize that the addition of a new family member is life changing for children already in the home, but other family changes like having a grandparent move in or an older sibling move out can be equally stressful. It is important to consider the developmental context of events and whether most children of a similar age would find the incident threatening or upsetting.

• Contextual Changes in the Family. Contextual changes are more enduring changes in life circumstances, either for better or worse, which provoke changes in the child’s perception of self, family, or feelings of relationship security. These changes may result in self-blame or stem from the actions of other family members, especially parents, creating a sense of betrayal.

• Parent Stress and Mental Illness. All parents face stress and feelings of being overwhelmed. It is important to assist parents to identify situations in which they know risk of stress is greatest. For example, certain developmental stages are commonly more taxing than others and many young children have increasing behavioral problems in the late afternoon hours as fatigue increases and energy levels lag. Primary care providers provide anticipatory guidance to develop interventions to help parents predict and minimize these “at-risk” times. Parents with mental illness are at risk for increased role strain and parenting difficulties because of how their condition affects their perceptions and coping skills.

• Impaired Parenting. Impaired parenting occurs when there is a mismatch between parenting behaviors and a child’s developmental or situational needs. This may result in inappropriate stimulation, inconsistent care, inappropriate supervision, developmentally inappropriate behavioral expectations, harsh words, child abuse or neglect, or child rejection. It is important to explore parenting influences. Parents face a tremendous challenge to adapt their parenting skills to the individual development and behavior of each child in their family. This may be evidenced by parental verbalization of dissatisfaction with their role, exacerbation, or inappropriate communication with the child. Child behaviors that may indicate impaired parenting include acting-out, developmental regression, and other aberrant behaviors.

• Parents’ Personal History of Being Parented. A significant body of research confirms the effect of the parents’ personal history of being parented on the quality of parenting provided to children. Parents’ recollections of how they were parented are powerful influences on parental perceptions of child behavior, beliefs about children and childrearing, and ultimately the parenting behaviors used in the home (Lieberman and Van Horn, 2009). It is important to have the parents share memories, good and bad, of their childhood and what they liked and disliked about the parenting they experienced (see Table 19-3).

• Family Health History. A thorough history of mental and developmental disorders in family members should be conducted, including school failure, delinquency, substance abuse, learning disorders, reading problems, mood disorders, personality disorders, schizophrenia, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), autism, genetic syndromes, and birth defects.

TABLE 19-3 History Taking: Areas for Assessment of Mental Health

| Topic | Sample Question | Potential Stressors |

|---|---|---|

| Behavioral manifestations: symptom analysis | “Please describe your child’s behavior. What seems to make it better or worse? How have you tried to help your child? How does the behavior make you feel? How do think your child feels?” | |

| Recent changes | “What events or changes have occurred in your family in the past year?” | |

| Contextual changes within the family | “Who lives in your home? Have there been any recent changes at home or changes in family relationships?” | |

| Recurring experiences | “Tell me about the things you find difficult or stressful as a parent, especially in caring for this child.” | |

| Parents’ personal history of being parented | “Tell me about your most favorite and least favorite memories of growing up. How is your parenting similar to and different from the parenting you received as a child? What are your expectations for your child?” | |

Disease Domain

• Prenatal and Birth History. Was the pregnancy planned and wanted; maternal illnesses and discomforts during the pregnancy; problems with the pregnancy; when prenatal care began; maternal alcohol, drug, and tobacco use; occupational or environmental exposures; results of prenatal testing; maternal weight gain during pregnancy; response of significant others to the pregnancy; presence of social support during the pregnancy; and maternal depression during pregnancy. Also, spontaneous or induced labor, length of labor, complications or medical conditions arising during labor, type of delivery, and delivery complications.

• Postnatal History. Gestational age, birthweight and length, problems after delivery (including hypoglycemia and hyperbilirubinemia), problems in the first 2 weeks of life, difficulty feeding, excessive irritability or lethargy, maternal postpartum depression, and results of newborn screening.

• Past Medical History. Childhood illnesses and traumatic injuries, especially neurological injuries and soft neurological signs of developmental significance (e.g., delayed speech).

Diagnostic Studies

Laboratory Studies

Pertinent laboratory tests (hemoglobin, ASO titer, blood lead level, serum electrolytes, drug tests for alcohol or illicit substances, or urinalysis) can rule out physical health problems with behavioral manifestations. The family history and findings on the physical examination may warrant chromosomal studies.

Common Mental Health Problems

Special Problems of Infancy and Early Childhood

Special Problems of Infancy and Early Childhood

At first glance the diagnoses seem to address familiar issues in infant and early childhood development, and are commonly addressed in pediatric primary care. Closer examination of the diagnostic criteria demonstrates that these diagnoses address more serious degrees of maladaptive behaviors, often with a significant parental dysfunction and distress. These issues are beyond the management abilities of most primary care providers who do not have extensive preparation in the field of infant mental health. One of the most common classifications (feeding disorders) is presented here, while regulation disorders are discussed in Chapter 15. The purpose of including them is to increase the primary care provider’s awareness of the range of conditions that are best treated by the infant mental health specialist.

Feeding Disorders

Feeding the infant and young child is a key parental task. Parents feel successful and competent when their infant or young child feeds vigorously and grows well. Conversely, feeding problems result in parental frustration and failing child growth and can provoke feelings of failure in many parents. Feeding problems are among the most stubborn challenges primary care providers encounter (see Chapter 10). A serious problem exists when an infant or young child fails to establish a regular feeding pattern based on hunger and satiety. The potential diagnoses cover problems in:

• State regulations that interfere with the infant’s ability to feed well

• Lack of reciprocity between the caregiver and infant during the feeding

• Infantile anorexia associated with a very active infant or young child who refuses food

• Sensory food aversions that are so numerous and extreme they result in nutritional deficiencies (Zero to Three, 2005)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree