(1)

Department Obstetrics & Gynaecology, St George Hospital, Kogarah, New South Wales, Australia

Abstract

When starting a patient on a conservative treatment program for stress incontinence, you must check whether there are uncorrected precipitating factors.

Managing Chronic Cough and Obesity

When starting a patient on a conservative treatment program for stress incontinence, you must check whether there are uncorrected precipitating factors.

It is demoralizing for the patient to work hard on a pelvic floor muscle training program if she has uncorrected chronic cough. We often see patients with chronic sinusitis, nasal polyps, postnasal drip, or asthma/chronic bronchitis, who have never seen an ENT surgeon or had optimal asthma therapy and so on.

Many general practitioners have had no training in managing incontinence during their undergraduate years. They may not realize that in the last 20 years, major advances have been made in conservative continence therapy, but we cannot achieve cure in the presence of an unrelenting cough. Hence, the urogynecologist may need to refer such patients to the appropriate ENT surgeon or respiratory physician.

Similarly, marked obesity should be reduced whenever possible. A large randomized controlled trial in 2010 showed that obese women who lost 10 % of their body weight were significantly likely to achieve at least a 70 % reduction in the frequency of incontinence [35]. Increases in body mass index relate directly to increased risk of incontinence [31].

In women with truncal distribution of fat, serum insulin levels may reveal insulin resistance, which warrant referral to an endocrinologist for metformin therapy to enhance weight loss [12].

By striving for reasonable weight loss, you may convert a patient from someone who needs surgery, with the attendant risks in the obese, into a woman who can achieve cure from a conservative program. In our unit, we do not routinely offer continence surgery to an obese woman without a serious trial of weight loss, because the weight loss may obviate the need for surgery and anesthesia (and the well-known surgical complication of detrusor overactivity or voiding difficulty; see Chap. 9).

Having said this, some obese women are trapped in a vicious circle. They need to exercise in order to lose weight, but whenever they exercise, they leak much more urine than in daily life. In this scenario, we usually strike a deal with the patient. If they can start the process and lose even 5 %, then we will offer surgery if supervised pelvic floor training does not achieve major benefit.

Treatment of Constipation

Uncorrected constipation (with chronic straining to defecate) is an acknowledged risk factor for stress incontinence. Patients need to learn how to manage this problem before they can expect a conservative program to work.

Further information is provided in Chap. 8 on obstructed defecation, but in essence management is as follows:

Colorectal surgeons recommend the use of bulking agents such as Metamucil, psyllium husks (from which Metamucil is manufactured), or Movicol.

Normacol granules are better tolerated by some patients.

A dessert spoon of psyllium husks or Metamucil should be dissolved in 400 ml of water in order to achieve a moist stool that is easily passed. Putting these substances onto the cornflakes in the morning is of no benefit, they must be dissolved in a plentiful amount of water!

A lubricating substance, such as Agarol or lactulose, can be added, to lubricate the bolus of stool as it moves down the gut.

In cases where the call to stool is felt, but the bolus of feces cannot be evacuated, then rectal glycerin suppositories are inserted to encourage defecation in this circumstance.

Simply getting the patient to eat a large juicy orange with three to four prunes first thing in the morning, with dilute hot tea, then sitting and relaxing on the toilet can be remarkably helpful.

Regular use of Senokot is now considered unwise, although intermittent doses help if all else fails. Studies by colorectal surgeons indicate that this agent stimulates the nerves of the gut to increase peristalsis and may induce a state of dependence. Eventually, the colonic nerves may become refractory.

Treatment of Postmenopausal Urogenital Atrophy

We all know that incontinence is more common as age advances, with a peak at the menopause. Because estrogen receptors are known to occur in the urethra, estrogen therapy should give benefit, by thickening the urethral epithelium, improving mucosal coaptation, and enhancing vascular tone in the periurethral vessels.

The Cochrane meta-analysis on use of estrogens for incontinence in 2002 analyzed both systemic and topical estrogen data. They concluded that topical estrogen has about a 50 % benefit for incontinence compared to a 25 % benefit for patients on placebo [23]. Systemic estrogen therapy (HRT) is no longer recommended, as two large trials have shown that stress incontinence was worsened in those on HRT compared with those on placebo [14, 18]. The most recent Cochrane review [8] concluded that four small trials of vaginal estrogen revealed a significant benefit (RR 0.74, 95 % CI 0.64–0.68) for improvement or cure of incontinence.

The objective benefit of topical vaginal estrogen cream in stress incontinence has received little study. In four small open (nonrandomized, noncontrolled) studies, three showed significant increase in urethral function tests, and one showed subjective benefit for continence (20 % dry, 55 % major benefit) [10]. A fifth study showed cure or major benefit on pad testing in 12 % of patients versus 0 % of controls (for review see Moore [24]).

Practical Advice for Patients

Many elderly women dislike the vaginal applicator that accompanies oestriol cream (Ovestin). It is cumbersome for those with arthritis, and many do not like inserting the applicator all the way into their vagina and then having to wash it. Some patients stop using it for these reasons (and the first two complaints apply to Vagifem tablets). We encourage patients to put a small amount on their finger and apply it around and just inside the vagina, last thing at night before sleep. Most women find this much more acceptable than using a messy applicator.

Many women ask whether the use of vaginal oestrogens will increase the risk of breast cancer. In general, the blood levels of oestriol are well below the menopausal levels (90 picomol/l) in women on Ovestin cream. However, a small study of women on Vagifem tablets [20] suggested caution in those on aromatase inhibitors to suppress early breast cancer.

Starting a Home-Based Pelvic Floor Muscle Training Program

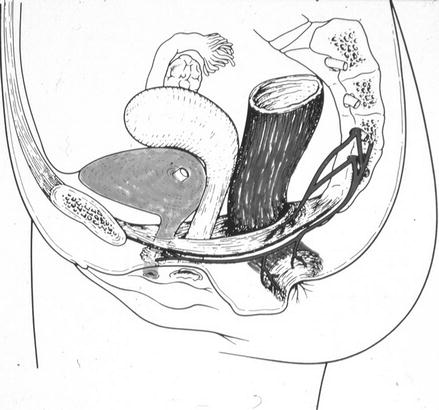

The first step in starting a pelvic floor muscle (PFM) training program should be done during the physical examination (see Fig. 6.1). That is, palpate the PFM digitally; make sure the patient can contract the correct muscle. Discourage her from:

Figure 6.1

Assessing the pelvic floor muscles

Contracting the gluteal muscles (lifting buttocks off the bed)

Contracting the adductor muscles (tightening thighs together)

Contracting the abdominal muscles (bearing down on the pelvic floor)

Contracting these muscles will not help and may make leakage worse.

Once the patient can contract the PFM correctly, ask her to squeeze as hard as she can, then count up to a maximum of 10 s. Observe when the muscle starts to fatigue, and stop the count there, for example, 6 s.

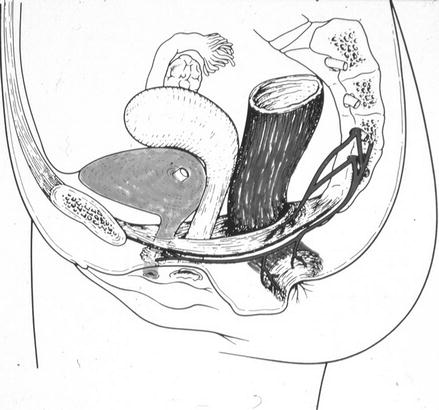

After the patient has gotten dressed, explain to her that the PFM is a muscle running from the pubic bone to the tail bone, with three openings in it (urethra, vagina, anus). We find it helpful to show a diagram such as that shown in Fig. 6.2, inasmuch as many patients do not understand this basic anatomy. Explain that the PFM is a postural muscle, like the erector spinae of the back. Think of the weight lifter who goes to the gymnasium. He usually has a very erect posture because of the strong resting tone of his large back muscles, but he can also lift heavy weights. The woman needs to train her PFM gradually, over 12–24 weeks, to increase the resting tone of the muscle, and it will also hypertrophy. Then the patient can train to squeeze the muscle against the “load” of coughing or sneezing.

Figure 6.2

Diagram of the pelvic floor muscle (Reprinted with permission from Swash [32]. Copyright 1990, John Wiley & Sons Limited)

The Role of the Nurse Continence Advisor

The assessment and basic explanation of the PFM (as above) are a task that any registrar or clinician should be able to carry out, as it only takes 1 min during the physical exam and 3 or 4 min of explanation time.

The following description of how to start a PFM training program may be too time consuming within the confines of a busy outpatient clinic. In this case, the patient should be referred to a nurse continence advisor (NCA) for the detailed training given below.

A physiotherapist (physical therapist) will also carry out this type of training program, but in some countries, the NCA is more readily available within a public hospital, with no cost to the patient. Referral to a physiotherapist can therefore be reserved for patients with a weak pelvic floor muscle, who may need electrical stimulation therapy, described later, especially if this incurs a cost.

First, the woman must contract the muscle as hard as possible for as long as she can, up to her maximum when fatigue is noted (e.g., 3 s).

Then rest the muscle for 5 s to let oxygen back into the muscle.

Explain that just squeezing the muscle over and over without this oxygen break will cause it to tire out, not strengthen.

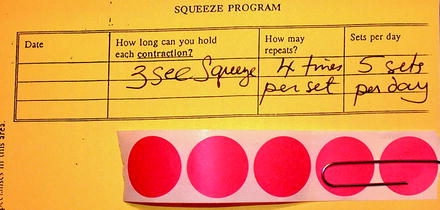

To make it easy to remember, we usually set a program that builds up numerically from her 3-s maximum, for example, 3-s squeeze, 4 squeezes per “set” or group, and 5 sets per day.

In this example, she would perform 20 contractions per day.

The five sets per day should be spread out over the day, not done all at once in the morning (because this causes fatigue also).

To help remember this, we would give five red adhesive dots to be placed around the house in places that are visited at different times of the day (near the toothbrush, kettle, telephone, television remote control, etc.). See Fig. 6.3.

Figure 6.3

Written PFM training program for a patient with an initial pelvic floor contraction of only 3-s duration, who is to do four contractions per set and five sets per day (five red dots given)

After the patient has strengthened her PFM for 3–4 weeks, she should then learn how to contract the muscle just before a cough or sneeze. This technique, called “the knack,” has been shown on pad testing to reduce leakage by up to 60 %/day [22].

In subsequent visits, the nurse continence advisor reiterates the initial explanation and upgrades the program (makes it harder). If a patient is sent to physiotherapy, the first visit always includes this type of explanation, with upgrading at follow-up. Even if the main complaint is urge incontinence, the PFM is used to defer micturition, so patients need to know how to contract it.

Who Should Be Referred for Physiotherapy?

If a woman cannot contract her PFM at the initial examination (or can only manage a weak flicker) despite your best efforts to help her locate the muscle, then she definitely needs referral to a pelvic floor physiotherapist (a physiotherapist who has undergone subspecialty training). She will assess the patient vaginally, use additional methods to help her identify the muscle, then move on to biofeedback or electrostimulation or both (see below for details).

The question then becomes the following: do women who can contract their muscles need a supervised training program, or can they practice at home with equally good results? This leads into the question, what form of PFM training is most effective?

In the last 30 years, many publications have considered this question. One problem is that the outcome measures used by the different authors varied greatly. Table 6.1 summarizes the results. The term “hospital PFMT” indicates that patients attended a pelvic floor physiotherapist weekly or monthly and had regular supervision of their training program.

Table 6.1

Objective results after pelvic floor muscle training for stress incontinence

Authors | N | Treatment | Results |

|---|---|---|---|

Wilson et al. [34] | 15 | Home PFME | Pads/24 h 11 % benefit |

45 | Hospital PFME | Pads/24 h 54 % benefit | |

Jolleys [19] | 65 | Home PFME | 48 % subjectively dry |

56 | Control | 0 % subjectively dry | |

Henalla et al. [17]

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|