Fig. 10.1

Diagram showing the first surgical step

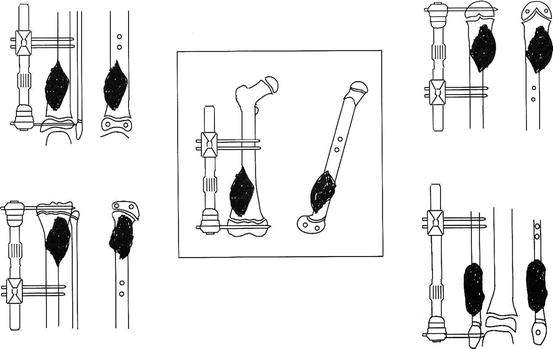

Fig. 10.2

(a–c) Devices used in young children for distal tibia, distal fibula, and distal radius (yellow) and in adolescents for proximal tibia and humerus (blue) and distal femur (red). All devices have a T-shaped piece in order to put the two epiphyseal pins perpendicular to the diaphysis

Fig. 10.3

Diagrams showing the placement of the pins in distal femur, proximal and distal tibia, proximal humerus, and distal fibula

Distraction is begun in the operating room and continues at the rate of 1–1.5 mm/day until 1 or 2 cm of distraction is achieved. During the first few days nothing happens, but after between 7 and 14 days of distraction the patient usually reports pain, and this indicates rupture of the growth plate: radiography will show disruption of the physis. In our series, the mean time over which distraction was applied was 10 days. This first phase can be carried out while the patient is finishing the course of neoadjuvant chemotherapy; despite the external fixator being in place, even intra-arterial procedures can be used without problems [9] (Fig. 10.4). We usually operate on a patient the day after the final intraarterial neoadjuvant procedure.

Fig. 10.4

(a) It not necessary to delay the protocol of treatment. The first surgical step is carried out during the pre-operative chemotherapy period. (b, c) In osteosarcoma patients, we use intra-arterial cisplatin as a part of the neo-adjuvant chemotherapy protocol. The angiogram also clearly shows that vascularization of the epiphysis is not connected with that of the metaphyseal tumor. We usually carry out resection of the tumor the day after the last intra-arterial neoadjuvant procedure

Phase two. En-bloc resection of the tumor is performed by diaphyseal osteotomy, leaving a wide margin. The metaphyseal end of the resection is already effected by the distraction. If the prior imaging methods clearly indicated an absence of tumor in the epiphysis, the operation is completed, in this second surgical step, by reconstruction with an intercalary graft (Fig. 10.5).

Fig. 10.5

Diagram showing resection and reconstruction

In the past, before the advent of MRI, with cases for which we could not be sure that the tumor had not involved the epiphysis, the resected tumor was sent immediately for histological examination, and chains of PMMA containing gentamicin were inserted into the space held open by the fixator. If the pathologist reported absence of tumor at the edges of the resected segment, the chains of beads were withdrawn and a bone graft was inserted (Fig. 10.4). If, on the other hand, the pathologist were to find tumor cells, the procedure would be to resect the epiphysis and reconstruct the limb by other means: prosthesis, osteoarticular allograft, or arthrodesis. In our series the latter scenario was only necessary in one patient, whose prosthetic reconstruction proceeded without problem, and who suffered no local recurrence. MRI has removed the uncertainty over epiphysis involvement, and the so the three-step technique described in this paragraph is no longer generally required (Figs. 10.6 and 10.7).