39 Congenital Anomalies of the Lung

Congenital Anomalies of the Airway

Etiology and Pathogenesis

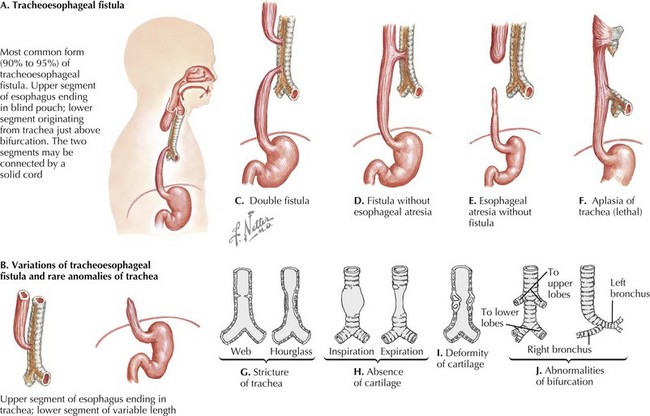

Tracheoesophageal fistula (TEF) occurs when there is incomplete mesodermal septation of the primitive foregut. The trachea is anatomically abnormal, causing primary malacia. In 85% of cases, there is a proximal blind-ending pouch with a distal fistula (Figure 39-1). The pouch expands and compresses the trachea, thus also causing secondary malacia. Less common types include the H-type fistula and upper esophageal fistula with distal atresia. The fistulae are often small and found between the larynx and the thoracic inlet.

Congenital Anomalies of Lung Parenchyma

Etiology and Pathogenesis

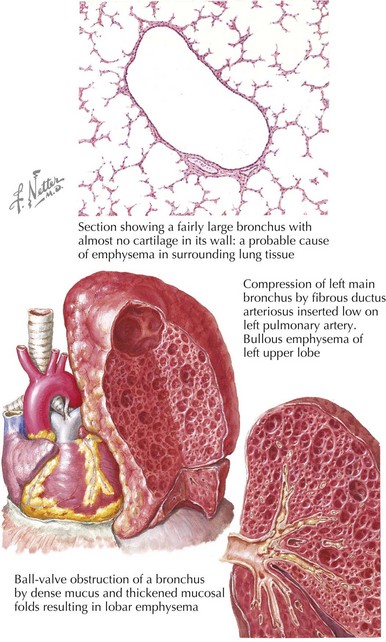

Congenital lobar emphysema (CLE) describes cases of an overdistended, hyperlucent lobe (Figure 39-2). The most commonly affected region is the left upper lobe (42% of cases). CLE may be caused by partial bronchial obstruction producing a ball-valve effect or a deficiency of bronchial cartilage. Less commonly, alveolar hyperplasia produces a polyalveolar lobe.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree