1st level: Basic level

Diagnostic laparoscopy

Sterilization

Needle aspiration of simple cysts

Ovarian biopsy

2nd level: Intermediate level (normal training during specialization in obs/gyn)

Salpingostomies for ectopic pregnancy

Salpingectomies

Salpingo-oophorectomies

Ovarian cystectomies

Adhesiolysis, including moderate bowel adhesions

Treatments of mild or moderate endometriosis—salpingostomy and salpingo-ovariolysis

3rd level: Advanced level (advanced procedures requiring extensive training)

Hysterectomy

Myomectomy

Treatment of incontinence

Surgery for severe endometriosis

Extensive adhesiolysis including bowel and ureter

Repair of simple intestinal or bladder injuries

4th level: (procedure under evaluation or practised in specialized centers)

Pelvic floor defects

Oncology procedures: lymphadenectomy, radical hysterectomy, and axilloscopy

Rectovaginal nodules

Other procedures not yet described

It is advised that the relatively simple procedures (level 1 and a part of level 2) can generally be performed by all credentialed gynecologists, whereas more difficult procedures (levels 3 and 4) have to be performed by gynecologists with a special interest and experience in laparoscopic surgery. For the level 4 procedures, it is advised to centralize these procedures in specialized institutions because of the multidisciplinary approach with general surgeons and urologists (e.g., severe endometriosis cases).

Data in scientific literature expose that both complication rate and conversion rate increase when the laparoscopic procedure turns to be more difficult. However, we have to take into account that the incidence of complications is also higher for these procedures when they are performed primarily by laparotomy.

20.2.4 Equipment and Tools

Due to the often ‘blind’ insertion of sharp instruments at laparoscopy (Veress needle and first trocar), this inherently can lead to complications which are not completely avoidable. To decrease the chance of such a complication, a number of standard precautionary measures have to be made.

(a)

At each laparoscopic procedure the bladder has to be emptied. When a longer procedure is expected, a catheter à demeure has to be applied.

(b)

The stomach preferably has to be emptied before the Veress needle is applied. Anxiety or a difficult intubation may result in aerophagia with probably a dilatation of the stomach below the level of the umbilicus. Furthermore, a dilated stomach can push the transverse colon below the umbilical level as well. These two occasions may result in visceral laceration when the Veress needle or first trocar is applied.

(c)

At introduction of the Veress needle, the patient should be in a horizontal position. If this position is altered (too early Trendelenburg position), the angle of application to Veress needle or first trocar might be changed as well. This will result in less angling with the chance of injury to the aorta. The application of the first trocar after applying pneumoperitoneum is also advised to be performed when the patient is placed in a horizontal position. Figure 20.1 shows this preventable situation.

Fig. 20.1

Too early placement in Trendelenburg position and the angle consequences of the introduced Veress needle

(d)

Testing of the Veress needle with an aspiration test or drop test gives relative information about the correct position of the Veress needle. In the past, these tests provided us with the best information about the position of the Veress needle. However, more recent data in literature showed us the relative value of these tests. A pressure level below 10 mmHg is the best informant of the position of the Veress needle tip. However, still relatively good information is obtained by the aspiration test to assure that the tip of the Veress needle is not applied intravascular or in a gastrointestinal organ.

A low initial abdominal pressure (<10 mmHg), followed by a free influx of CO2, is a reliable indicator of correct intraperitoneal Veress needle placement. Still, however, there are only insufficient high-quality comparative studies available on safety and effectiveness of the different aspects in these specific open- and closed-entry techniques. Furthermore, the peritoneal hyper distention has only been studied and found to be safe in healthy female patients with low ASA score (e.g., score 1 or 2). The latter technique (application of an intra-abdominal pressure of 20–24 mmHg) results in an increase size of the gas bubble and creates more distance between the abdominal wall and the organs at risk.

An internationally adapted open Hasson technique is an alternative for the closed entry technique. However, the number of specific entry complications has not been diminished with either approach. Both, the number of vascular and gastrointestinal injuries are equal at each technique applied.

20.2.5 Anesthesia and Pneumoperitoneum

Due to the relatively high intra-abdominal CO2 pressure and the (steep) Trendelenburg position, inherently anesthesiological problems may occur. Furthermore, the extensive use of cold fluids intra-abdominally can lower the patient’s temperature with its consequences.

20.3 Intraoperative Complications

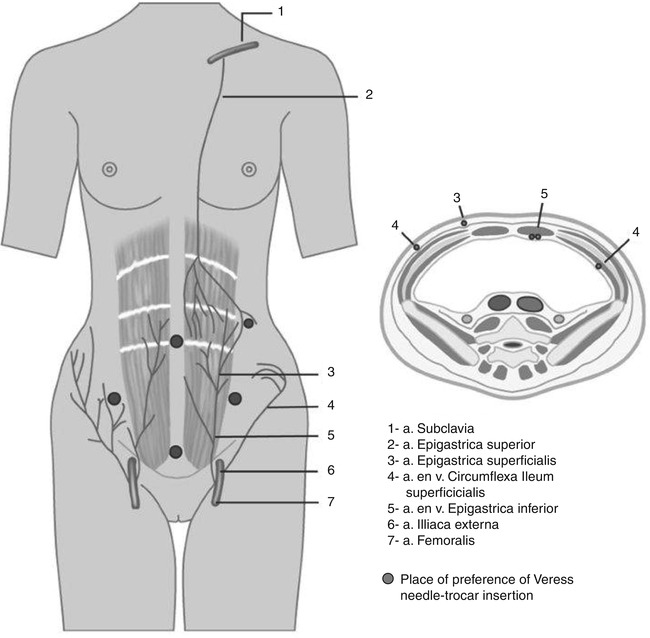

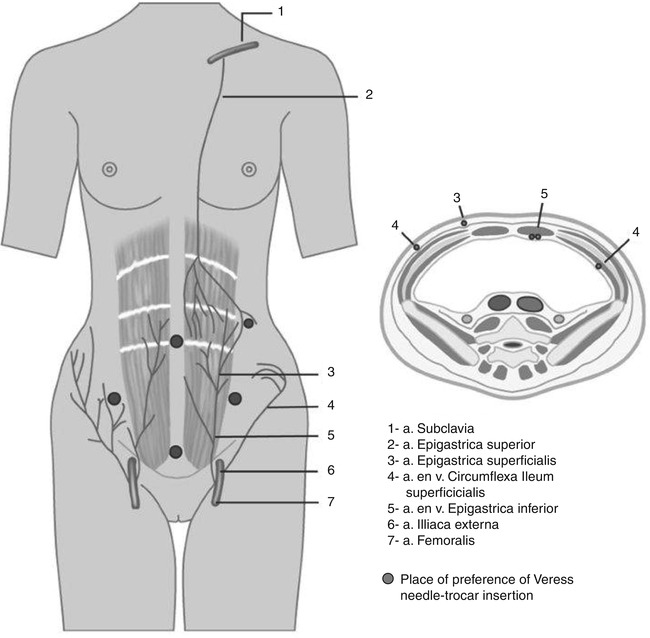

20.3.1 Abdominal Wall Bleeding

A lesion of an epigastric vein or artery is the most common observed complications of a bleeding of the abdominal wall. The given incidence in literature varies between 0.17 and 6.4 per 1,000. This large range can to be explained to the fact that most studies on this subject are of retrospective origin and no discrimination is made between a superficial abdominal wall bleeding and an intra-abdominal bleeding.

20.3.1.1 Prevention

Most bleedings of the epigastric veins are caused as a result of blind insertion of the additional side trocars. Precautions to avoid this complication are relatively simple. Knowledge of the anatomy of the abdominal wall veins (Fig. 20.2), transillumination of the abdominal wall by the laparoscope, and insertion of the secondary side trocars only under direct vision is one of them. However, an abdominal wall bleeding is not always directly recognizable due to the tamponade of the trocar during the surgical procedure. If this trocar is accidentally removed during the operation, a bleeding or the development of a hematoma could originate. Securing of the trocar with a screw (cave: diameter of the incision is enlarged) or a stitch can prevent the unintended removal of the trocar during the procedure.

Fig. 20.2

Anatomical pathway of arteries and veins in the abdominal wall

20.3.1.2 Treatment

Usually, a reactive policy is recommended for an abdominal wall bleeding, especially since the trocar tamponades the manifestation of the bleeding. However, when the bleeding persists and is visible by dripping of blood into the abdomen, besides the trocar, this is usually a result of a lesion of the epigastric inferior vein. Several ways are described to stop the bleeding from the trocar side. First, the vein can be coagulated by bipolar coagulation. However, when the bleeding persists it is advised to leave the trocar in situ and apply a Foley catheter into the trocar, remove the trocar and clamp it at the abdominal side. Tamponade with a catheter balloon (filled with saline) tamponades the bleeding by pressure from the inside of the balloon toward the peritoneal side of the abdominal wall. Other alternatives are by applying a laparoscopic stitch to the abdominal wall or enlarging the incision to locate the bleeding and then the vein can be stitched in a conventional way.

20.3.2 Intra-abdominal Bleeding

In general, intra-abdominal bleeding is a result of the applied technique or, similar to conventional surgery, a result of ‘bad’ luck during the procedure. The incidence of this complication as a result of the blind insertion of Veress needle or first trocar is 2.7/1,000 or 2.4–2.7/1,000, respectively. Sometimes, an intra-abdominal bleeding is not visible or manifest during the procedure because of a combination of factors. The Trendelenburg position and the high intra-abdominal pressure (14–16 mmHg) give a relative supine hypotension. At the end or after the procedure, when this combination of factors is dissolved, intra-abdominal bleeding can become manifest.

20.3.2.1 Prevention

Apart from the application of general preoperative precautions, there are not many means to prevent a bleeding. Like in conventional surgery, one surgical procedure has more bloody course than the other. Some preventive measurements to comply within laparoscopic surgery are that at the end of the operation the intra-abdominal overpressure as well as the Trendelenburg position have to be released. By inspecting the operating field, an intra-abdominal bleeding can be seen and arrangements for stopping the bleeding can be made. One has to be aware that a manual overshoot during the blind insertion of either the Veress needle or the first trocar can occur. Precaution to overshoot is that when the Veress needle has passed the peritoneum (after two clicks), no further application is necessary intra-abdominally. The same is applicable for the first trocar. The extreme thin patient (BMI < 18) and children are especially at risk for lesions of aorta and vena cava because these structures are situated just under the skin. Also, the angle in which the instruments are applied is of importance. The fatter the patient, the more at 90° angle the instruments have to be introduced.

20.3.2.2 Treatment

The occurrence of an intra-abdominal bleeding does not mean that the planned laparoscopic procedure has to be abandoned. Many bleedings can primarily be treated and stopped with bipolar coagulation. Also, clips or stitches can be used to stop the bleeding as well as the application of an endoloops. Furthermore, a sterile gauze can be applied toward the diffuse bleeding surface to tamponade the bleeding for a while. Lastly, there are several hemostatic products available which are laparoscopically applicable.

20.3.3 Gastrointestinal Lesions

Gastrointestinal lesions can be a result of the blind insertion of the Veress needle or the first trocar and are therefore entry-related complications. Furthermore, gastrointestinal lesions can occur due to the technique used in the procedure. One of the biggest problems of gastrointestinal lesions is that they are not always immediately noticed. Some described that only in 1/3 of cases these lesions are observed intraoperatively. When, after the operation, abdominal pain occurs as a result of generalized peritonitis, the lesion becomes manifest. When the lesion is a result of a sharp trauma (e.g., Veress needle, trocar or laceration during sharp adhesiolysis), clinical signs will be manifest within 72 h. In contrast, thermo damage due to electric coagulation or laser coagulation are manifest sometimes just after 4 or 10 days. At reintervention, it is from macroscopic point of view difficult to distinguish if the lesion is a result of a sharp or a coagulation trauma. In both cases, the perforation has a macroscopic whitish area of necrosis at the lesion. At microscopic level, however, a distinction between lesions can be made. At electrocoagulation trauma, dead amorphous tissue without polymorphic core infiltration is visible. Perforation lesion as a result of sharp trauma shows capillary ingrowth, leukocyte infiltration, and fibrin deposition at the edges of the wound.

Gastrointestinal lesions can occur both on the small intestine and on the colon. Small intestinal lesions usually occur as a result of a trauma by the first trocar, usually in patients with a history of prior laparotomy. However, also blunt dissection of small intestines may result in lesions of these organs. Colon lesions usually occur as a result of introducing too blunt trocars with too much force, usually in absence of an adequate pneumoperitoneum.

20.3.3.1 Prevention

An adequate pneumoperitoneum (>20 mmHg) ensures that the gastrointestinal organs are located far from the abdominal wall. This decreases the risk that these gastrointestinal organs can be damaged. The stomach has to be emptied before the operation starts. In this context, it is interesting to see that gastrointestinal lesions at the open-entry technique usually are recognized earlier than in blind technique. In general, it is found that patients with a prior laparotomy have a higher incidence of gastrointestinal lesions and operations where extensive adhesiolysis is performed are at risk.

When, during the closed entry, a bowel lesion occurs or is suspect, it is advised to leave the Veress needle or trocar in situ to identify the lesion during laparotomy. Finally, at the end of the laparoscopic procedure, trocars have to be removed under direct vision in order to prevent slippage of the small gastrointestinal organs in the abdominal defect due to the evolved negative abdominal pressure. At removing the trocars, this can lead to herniation and incarceration of the bowels or omentum.

20.3.3.2 Treatment

Instantly noticed perforation of small intestines or colon can be repaired immediately by stitching the defect. It is well established that bowel preparation does not play a role anymore for the clinical results after repairing a gastrointestinal lesion. However, when a bowel lesion has to be repaired after a longer period of time, this preparation is debatable. When at the fifth or sixth postoperative day, a patient reports abdominal tenderness, slight fever, nausea and/or vomiting with diminished appetite, and a progression in these symptoms, it is suspect for an (unnoticed) gastrointestinal lesion. Lesions with a later manifestation have a higher morbidity and are usually treated by laparotomy. Small intestine lesions are usually treated with an end-to-end anastomosis. However, the latter depends if the blood supply is not damaged. Treatment of lesions of the colon, recognized at a later date, depends on the stage of the peritonitis and will still be treated in the conventional way with a Hartman procedure.

20.3.4 Bladder Lesions

The occurrence of a lesion of the bladder is rare and usually occurs only when a patient had prior abdominal surgery (e.g., a Caesarean section) or when the bladder is preoperatively not emptied. Furthermore lesions can also occur after coagulation. Operations at risk for the occurrence of bladder lesions are the treatment of endometriosis (ablation), adhesiolysis, bladder suspension operations, and the laparoscopic hysterectomy. The incidence found in literature varies between 0.06 and 1.2 %, which includes the occurrence of fistulas postoperatively. For many years, the laparoscopic hysterectomy (LH) was considered at risk for bladder lesions. For the latter, a recently published study from Finland showed that when experience with this surgical procedure increases, a decrease of these lesions was found. Nowadays, an incidence of 0.34 % is given for lesions at the urogenital tract including bladder and ureter lesions. This is at the same level as given for the abdominal or vaginal hysterectomy. Specifically for bladder lesions, they can stay unnoticed. However, in most cases (90 %) these lesions are directly recognized. This is in contrast with ureter lesions, which become manifest in most cases (80 %) after initial operation.

20.3.4.1 Prevention

For gynecological laparoscopic procedures, it is mandatory to empty the bladder before the procedure starts. Long-lasting procedures require a catheter a demeure. A procedure, very close to the bladder, or when there is doubt about the exact location of the boundary of the bladder a retrograde filling of the bladder is optional. With 350 cc saline solution the edges of the bladder are easily found. When secondary trocars are removed, it is important to visualize intra-abdominally if there is no leakage of urine. Tamponade of the lesion intraoperatively holds the lesion occult. When after a procedure hematuria is found, or gas (CO2) is seen in the catheter bag, this could direct to a bladder lesion.

20.3.4.2 Treatment

Treatment options depend on the size of the lesion. When the lesion is very small (<5 mm), a catheter can be put into the bladder for 5–7 days and a spontaneous healing can occur. However, when a big laceration is found this can be stitched laparoscopically. This stitching can be done in one layer with continuous running sutures. Some advise to control the stitch with cystoscopy, especially to evaluate the orifices of the ureter. Drainage for 7 days and antibiotic prophylaxis followed by a cystogram postoperatively after 7 days are advised. The latter option depends on the severeness of the lesion and its location.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree