Look in the mouth. If you can see anything obvious occluding airway then remove it if it is easy to do so but don’t sweep with your finger further than you can see as you may end up pushing something further down into the airway.

Open the airway. Use either a ‘head tilt, chin lift’ or ‘jaw thrust’ manoeuvre. Always use a jaw thrust if you suspect a cervical spine injury.

Open the airway. Use either a ‘head tilt, chin lift’ or ‘jaw thrust’ manoeuvre. Always use a jaw thrust if you suspect a cervical spine injury.

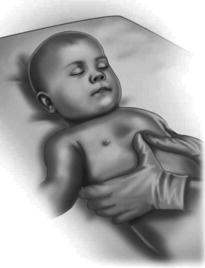

– Head tilt, chin lift. Put one hand on the forehead and one finger under the bony part of the jaw and tilt the head. For babies up to 1 year old, move their head so that it is in a neutral position (i.e. with their face parallel to the surface they are lying on). For children, their head should be moved so that their neck is partly extended into a ‘sniffing’ position. Be careful to place your fingers on the bony part of the jaw as pressing on the soft tissues can occlude the airway. See Fig. 5.2 for babies and Fig. 5.3 for child head position in head tilt, chin lift.

– Jaw thrust. Position yourself above the child’s head so that you are looking down towards their feet. Place the ring and middle finger of each hand at the angle of the jaw on both sides and the fleshy part of your thumb on their cheekbones. Using both hands together, pull up on the angle of the jaw with your fingers and press down with your thumbs in order to bring the lower jaw forward. See Fig. 5.4.

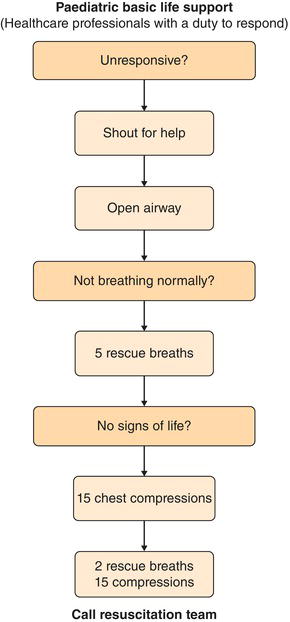

Figure 5.1 Paediatric Basic Life Support algorithm. Reproduced with permission from Resuscitation Council UK.

Figure 5.2 Opening the airway of an infant using a head tilt and chin lift. (a) Airway occluded. (b) Airway opened using head tilt and chin lift.

Breathing

Once you have opened the airway you need to assess for normal breathing.

Look, listen and feel. Look for chest and abdominal movements, listen for airflow at mouth and nose and feel for breath on your cheek. This should be done for no more than 10 sec.

Look, listen and feel. Look for chest and abdominal movements, listen for airflow at mouth and nose and feel for breath on your cheek. This should be done for no more than 10 sec.

Give five rescue breaths. If the child is not breathing or is taking only occasional gasps then give five rescue breaths. If you don’t have access to any equipment then seal your lips tightly around the child’s mouth and pinch their nose, or for a baby seal your lips around their nose and mouth. If you have a pocket mask you can use this to deliver rescue breaths using your breath. If you have access to a bag-valve mask this can be used to deliver the breaths.

Give five rescue breaths. If the child is not breathing or is taking only occasional gasps then give five rescue breaths. If you don’t have access to any equipment then seal your lips tightly around the child’s mouth and pinch their nose, or for a baby seal your lips around their nose and mouth. If you have a pocket mask you can use this to deliver rescue breaths using your breath. If you have access to a bag-valve mask this can be used to deliver the breaths.

Watch for chest movement. If there is no chest movement as you deliver a rescue breath, reposition the child’s head to ensure that the airway is open and make sure that you have a tight seal around the child’s nose and mouth before delivery of the next breath.

Watch for chest movement. If there is no chest movement as you deliver a rescue breath, reposition the child’s head to ensure that the airway is open and make sure that you have a tight seal around the child’s nose and mouth before delivery of the next breath.

Circulation

Feel for a pulse and look for signs of life. After you have delivered the five rescue breaths, feel briefly for a pulse and look for signs of life. This should take no more than 10 sec. In a child, feel for carotid or femoral pulses; in an infant, feel for brachial or femoral pulses. It can be difficult to be sure of whether or not you can feel a pulse within 10 sec so also look for signs of life, which might be coughing or gagging in response to rescue breaths or movement.

Feel for a pulse and look for signs of life. After you have delivered the five rescue breaths, feel briefly for a pulse and look for signs of life. This should take no more than 10 sec. In a child, feel for carotid or femoral pulses; in an infant, feel for brachial or femoral pulses. It can be difficult to be sure of whether or not you can feel a pulse within 10 sec so also look for signs of life, which might be coughing or gagging in response to rescue breaths or movement.

Start chest compressions. If there are no signs of life or the child’s pulse is not palpable or their heart rate is less then 60 beats per minute, commence chest compressions. If you are in any doubt about whether or not you can feel a pulse and the child is showing no signs of life, commence chest compressions.

Start chest compressions. If there are no signs of life or the child’s pulse is not palpable or their heart rate is less then 60 beats per minute, commence chest compressions. If you are in any doubt about whether or not you can feel a pulse and the child is showing no signs of life, commence chest compressions.

– Where? In a child, feel for the xiphisternum and place the heel of your hand just above this point (on the lower half of the sternum). You can use two hands if needed. In babies, feel for the xiphisternum and place two fingers just above this point (on the lower half of the sternum). If there are two of you providing Basic Life Support then a more effective method is for one person to stabilise the airway whilst the other wraps their hands around the baby’s chest and uses both thumbs to compress at this point on the lower half of the sternum. See Fig. 5.5 for two-hand technique.

– How hard? Don’t be afraid to press quite hard. The chest compressions need to compress to a depth of at least a third of the chest in order to be effective.

– How fast? Chest compressions should be given at a rate of 100–120 beats per minute.

– How many? Do 15 chest compressions.

– What next? After your 15 chest compressions, give two more breaths and continue at a ratio of 15:2. Continue like this until the child moves or takes a breath. After 1 min of resuscitation if no-one has come to help, go and call the emergency services (999) yourself or put out a paediatric crash call if you are in hospital (2222). As soon as you have done this, restart chest compressions and ventilations until help arrives.

Choking child

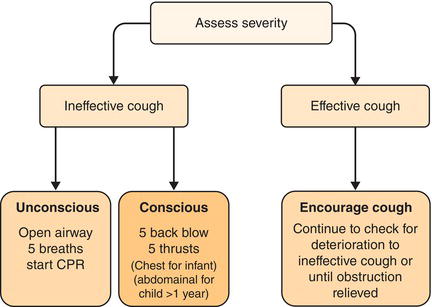

See Fig. 5.6 for paediatric choking management algorithm. See Video 1 for a demonstration of how to manage a choking child.

Choking often occurs when children are playing or eating and is frequently witnessed by their parents or carers who will give a clear history of the child putting something in their mouth and then choking.

Figure 5.6 Paediatric choking management algorithm. CPR, cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Reproduced with permission from Resuscitation Council UK.

History

Ask about:

sudden onset

sudden onset

playing with small objects just prior to onset

playing with small objects just prior to onset

eating

eating

coughing.

coughing.

Symptoms

Panic

Panic

Coughing

Coughing

Unable to breathe

Unable to breathe

Signs

Stridor

Stridor

Gagging

Gagging

Coughing

Coughing

Cyanosis

Cyanosis

Decreased consciousness

Decreased consciousness

Immediate management

Is the child coughing effectively or not?

Effective coughing. This means that they are able to talk or cry, make a loud sound whilst coughing and are able to take a deep breath before each cough. If the child is coughing effectively simply reassure them and encourage them to continue coughing.

Effective coughing. This means that they are able to talk or cry, make a loud sound whilst coughing and are able to take a deep breath before each cough. If the child is coughing effectively simply reassure them and encourage them to continue coughing.

Ineffective coughing. The child has a silent or quiet cough and is unable to vocalise or breathe. They may have cyanosis or reduced conscious level. If this is the case then what you do depends on whether or not the child is conscious.

Ineffective coughing. The child has a silent or quiet cough and is unable to vocalise or breathe. They may have cyanosis or reduced conscious level. If this is the case then what you do depends on whether or not the child is conscious.

Managing ineffective coughing (conscious child)

Shout for help.

Shout for help.

Give five back blows.

Give five back blows.

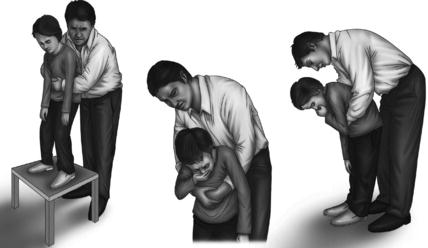

– Child. Deliver short, sharp blows between the shoulder blades with the heel of your hand. The aim should be to relieve the obstruction with each blow rather than to deliver all five.

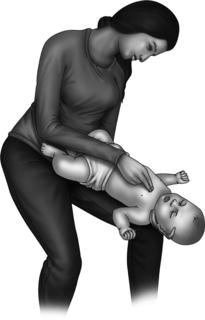

– Baby. Sit on a chair or kneel on the floor. Support the baby’s head by placing your thumb and index finger around the lower jaw, taking care not to compress the soft tissues under the jaw. Place the baby face down across your lap and deliver five sharp blows to the middle of the back with the heel of the hand. Do not be afraid to do this quite forcefully in order to relieve the obstruction. See Fig. 5.7 for how to hold a baby for back slaps.

Deliver five abdominal or chest thrusts. If the back blows do not relieve the airway obstruction, deliver five abdominal thrusts.

Deliver five abdominal or chest thrusts. If the back blows do not relieve the airway obstruction, deliver five abdominal thrusts.

– Child. Stand behind the child, clench one of your fists and place it against the child’s abdomen approximately midway between the umbilicus and xiphisternum. In small children you may need to kneel down or stand the child on a chair in order to do this effectively. Pull sharply inwards and upwards five times. See Fig. 5.8 for how to perform abdominal thrusts on a child.

– Baby. Turn the baby over on your knee, keeping them in a head-down position. Place two fingers just above the xiphisternum (in the same site as for chest compressions) and press down with short, sharp thrusts. These should be slower and more forceful than for chest compressions. The aim is to remove the obstruction with each thrust rather than to deliver all five and these need to be done firmly to generate enough intrathoracic pressure to relieve the obstruction. See Fig. 5.9 for how to hold a baby for chest thrusts.

Managing ineffective coughing (unconscious child)

If a child or baby becomes unconscious as a result of choking, commence Basic Life Support as detailed above. Recheck the mouth after each cycle of chest compressions to look for a foreign body that may have been dislodged.

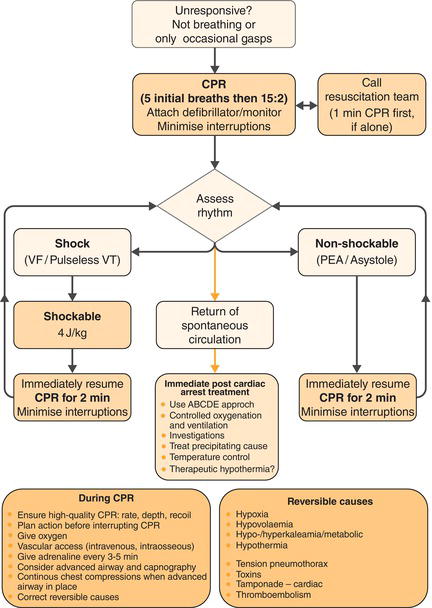

Advanced Life Support

See Fig. 5.10 for a paediatric Advanced Life Support algorithm.

If you are in a hospital setting you will have access to more equipment which will allow you to perform more advanced support to children who are unresponsive. Follow the same steps as for Basic Life Support but you can use equipment to aid the process.

Figure 5.10 Paediatric Advanced Life Support algorithm. CPR, cardiopulmonary resuscitation. PEA, pulseless electrical activity; VF, ventricular fibrillation; VT, ventricular tachycardia. Reproduced with permission from Resuscitation Council UK.

Airway management

Airway manoeuvres. Use a ‘head tilt, chin lift’ or a ‘jaw thrust’ as detailed in the Basic Life Support section. For examples of how to do each of these manoeuvres see Video 1.

Airway manoeuvres. Use a ‘head tilt, chin lift’ or a ‘jaw thrust’ as detailed in the Basic Life Support section. For examples of how to do each of these manoeuvres see Video 1.

Airway adjuncts. If you are struggling to keep the child’s airway open using the manoeuvres mentioned above, you can use pieces of equipment to help keep the airway open.

Airway adjuncts. If you are struggling to keep the child’s airway open using the manoeuvres mentioned above, you can use pieces of equipment to help keep the airway open.

– Oropharyngeal (Guedel) airway. You can use one of these to help keep the tongue and soft tissues from occluding the airway but they will only be tolerated in a child who is unconscious. If the child’s gag reflex is intact, insertion of a guedel may induce vomiting and it should be removed. Check you are using the correct size by making sure that the airway is long enough to reach from the middle of the incisors to the angle of the jaw when resting along the side of the child’s face. It can help to use a tongue depressor as you insert it to get the airway in the correct position.

– Nasopharyngeal airway. In a child with facial injury or lip and tongue swelling or a child who is having a seizure, this can be a useful type of airway adjunct. It is sometimes also better tolerated than oropharyngeal airways in children who are not completely unconscious. Use of a nasopharyngeal airway is contraindicated in trauma patients with a suspected base of skull fracture. Make sure that you put a safety pin through the end of the tube which is to remain outside the child if you are not using a brand of tube that has its own stopper on the end. This is to prevent the airway from accidently sliding all the way into the nasopharynx. The correct airway size to use is one that is roughly the same diameter as the child’s little finger. If a small size of nasopharyngeal airway is not available a shortened endotracheal tube may be used.

Tracheal intubation. The above measures are usually only temporary solutions to open the airway and a child who remains unconscious despite initial resuscitation is likely to need tracheal intubation. This should only be done by someone experienced so do not attempt this on your own unless you have had adequate training.

Tracheal intubation. The above measures are usually only temporary solutions to open the airway and a child who remains unconscious despite initial resuscitation is likely to need tracheal intubation. This should only be done by someone experienced so do not attempt this on your own unless you have had adequate training.

Breathing management

If a child is not breathing or is only making occasional gasping breaths then start Basic Life Support. If you are in a hospital setting you may have access to the following equipment to help you with this.

Pocket masks. These are facemasks designed for giving mouth-to-mouth resuscitation. They are available in many community settings as well as in the hospital (and they are inexpensive so you may wish to buy one to keep in your car or carry with you). Some of them have ports to which you can connect an oxygen supply to increase the percentage of oxygen delivered by your breaths. They have an air-filled rim to allow a firm seal around the patient’s nose and mouth. If you have to use one of these to resuscitate an infant, you can turn it upside down in order to get a better seal. See Fig. 5.11.

Pocket masks. These are facemasks designed for giving mouth-to-mouth resuscitation. They are available in many community settings as well as in the hospital (and they are inexpensive so you may wish to buy one to keep in your car or carry with you). Some of them have ports to which you can connect an oxygen supply to increase the percentage of oxygen delivered by your breaths. They have an air-filled rim to allow a firm seal around the patient’s nose and mouth. If you have to use one of these to resuscitate an infant, you can turn it upside down in order to get a better seal. See Fig. 5.11.

Bag-valve-mask ventilation. This equipment is available in each resuscitation bay in most hospitals and on the crash trolley.

Bag-valve-mask ventilation. This equipment is available in each resuscitation bay in most hospitals and on the crash trolley.

– When to use it. This can be used instead of a mouth-to-mouth technique when delivering Basic Life Support ventilations if there are other people helping you. If you are on your own then it will take too long to switch between compressions and ventilations if you try to use this method and you should instead stick to using mouth-to-mouth techniques until help arrives. If you are ventilating a child who does not need chest compressions then ventilate at a rate of 12–20 breaths per minute.

– Attach an appropriately sized mask to the bag and connect it to the oxygen supply. For children, a triangular-shaped mask can be used whereas for babies a circular mask often allows you to form a better seal and a T-piece is often used instead of a bag-valve-mask to allow ease of ventilation (see Chapter 9 – Neonates for more detail).

– Form a tight seal with the mask around the child’s nose and mouth and keep the airway open as you give ventilations. Make sure that the cuff around the edge of the mask is inflated with air (use a syringe to do this if it is not already inflated) and press down only on the firm part of the mask (not the air-filled cuff) in order to gain a good seal against the child’s face.

– Use the c-shape technique if alone. If you are the only person available to manage airway and breathing, you can deliver ventilation on your own. Use one hand to hold the mask onto the child’s face and the other to squeeze the bag to deliver ventilation. This technique can require some practice to get right. With the hand holding the mask, form a c-shape with your thumb and forefinger and press down with the sides of these fingers onto the firm part of the mask. Then place your ring finger and little finger under the angle of the jaw and pull forwards towards the mask. This allows you to form a tight seal and helps to keep the airway open by lifting the lower jaw. Make sure that you have the appropriate amount of head tilt (as long as there is no suspicion of cervical spine injury) to keep the airway open. See Fig. 5.12.

– Two-person technique is more effective. If there are enough people present then the two-person technique can be much more effective, particularly if you are inexperienced. To do this, one of you uses two hands to hold the mask in place whilst the other squeezes the bag to deliver ventilation. The person holding the mask can either use the c-shape technique but with both hands or use the heels of both thumbs to press down on the mask whilst using the fingers under the angles of the jaw on both sides to do a jaw thrust manoeuvre. See Fig. 9.4 in Chapter 9 – Neonates.

– Watch to make sure that the chest rises and falls as you deliver each ventilation. If it does not then readjust the head tilt (as long as there is no cervical spine injury) and make sure you have a tight seal with the mask before trying again.

Circulation management

In a child who has had a respiratory or cardiac arrest, the most important thing is to start effective Basic Life Support, so if you are in doubt about further management, continue with this until further help arrives. If you are confident and have been trained how to use a defibrillator and resuscitation drugs then you may wish to start Advanced Life Support for management of a cardiac arrest.

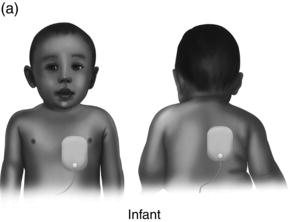

Put on the electrode pads. Dry the child first if they are wet. Position one electrode over the apex of the heart (just below the nipple in the midclavicular line) and one just below the right clavicle or in an infant, place one pad on the back below the left scapula and one on the chest, to the left of the sternum. See Fig. 5.13.

Put on the electrode pads. Dry the child first if they are wet. Position one electrode over the apex of the heart (just below the nipple in the midclavicular line) and one just below the right clavicle or in an infant, place one pad on the back below the left scapula and one on the chest, to the left of the sternum. See Fig. 5.13.

Automated devices. If you are using an automated device it will instruct you as to whether or not to deliver a shock.

Automated devices. If you are using an automated device it will instruct you as to whether or not to deliver a shock.

Manual devices. To use a manual device, you need to be able to interpret whether the child is in a shockable or non-shockable rhythm.

Manual devices. To use a manual device, you need to be able to interpret whether the child is in a shockable or non-shockable rhythm.

Drugs. Which drugs are given and when will depend on whether the child’s heart is in a shockable or non-shockable rhythm.

Drugs. Which drugs are given and when will depend on whether the child’s heart is in a shockable or non-shockable rhythm.

Training in advanced resuscitation using defibrillators and medications in children who have had a cardiac arrest is provided on paediatric Advanced Life Support courses. A brief summary is available to download for free from the Resuscitation Council website (www.resus.org.uk). See also Fig. 5.10 for a paediatric Advanced Life Support algorithm.

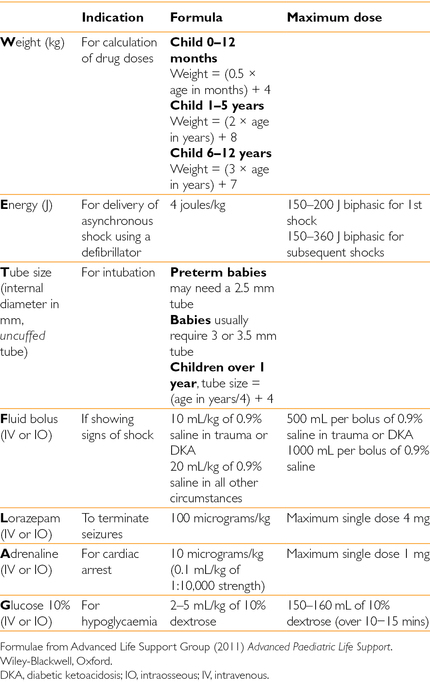

Emergency drugs

Whereas in adult Advanced Life Support there is one set dose for each of the emergency drugs used, with children this is obviously not possible because you would not give the same dose to a 9 month old as to a 12 year old. Doses are calculated by weight but in an emergency situation you may not have a recent weight for the child available so instead there are formulas that can be used to estimate a child’s weight based on their age (see Table 5.1). Obviously if you have a recent actual weight for the child this is more accurate and you should use this instead.

Top Tip

Top TipYou would never be expected to perform advanced management of a cardiac arrest by yourself or lead a resuscitation as a junior member of the team. However, it can be useful to know the formulas used in a paediatric resuscitation so that you can start doing some of the calculations for common drugs that may need to be used. Many resuscitation rooms will have a whiteboard or something similar so that you can write the formulas up for everyone else to see. Go to www.wileyhandsonguides.com/paediatrics for a small printable version of these formulas that you can attach to your ID badge.

Top Tip

Top TipA commonly used mnemonic for calculations needed for a paediatric resuscitation is WET FLAG. See Table 5.1 for details. It is also possible to download a chart with precalculated doses of emergency medications for children of different ages from the Resuscitation Council website (www.resus.org.uk). You may wish to print out a copy to keep on your resuscitation trolley if one is not already available or to stick on the wall in resuscitation rooms.

ABCDE approach

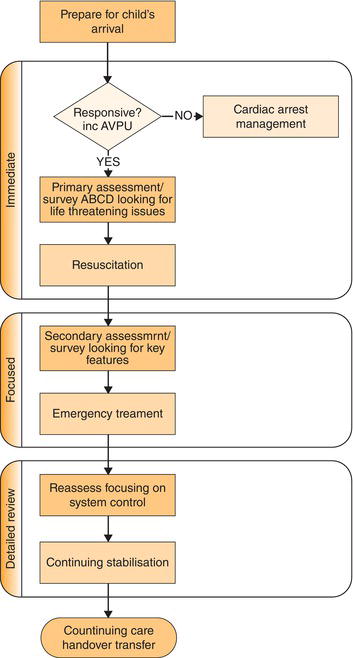

See Fig. 5.14 for an algorithm of the structured approach to management of a sick child.

Regardless of the specific situation, it is really important to take a systematic approach to the management of an acutely unwell child. This allows you to make sure that you address any potential problems in the order of most urgent priority and avoids you missing anything. When using this approach, never move on to the next step until you have dealt with any problems identified in the earlier systems. This can be hard to stick to sometimes but is really important. For example, if a child has a wound that is bleeding it can be tempting to deal with this first but if they are unconscious and their airway is occluded, this will kill them much more quickly than the bleeding and must be dealt with first. The ‘A–E’ system for approaching resuscitation is well established and is taught on both paediatric and adult emergency life support courses. It is a simple way of remembering what you have to do. The letters stand for: Airway, Breathing, Circulation, Disability, Exposure.

A – Airway

The most urgent thing to assess in any emergency situation is whether air is able to travel effectively in and out of the trachea. Problems can occur in the oropharynx or the trachea itself.

Airway assessment

Is the child able to talk or cry?

Is the child able to talk or cry?

Are there any additional sounds? Listen for any evidence of stridor or sturtor. These are squeaking or snoring noises as the child breathes in caused by a turbulent airflow as a result of partial airway occlusion. The volume of the noise is not an indication of the severity of obstruction.

Are there any additional sounds? Listen for any evidence of stridor or sturtor. These are squeaking or snoring noises as the child breathes in caused by a turbulent airflow as a result of partial airway occlusion. The volume of the noise is not an indication of the severity of obstruction.

Are they showing any signs of see-saw breathing? This is when the chest is drawn in and the abdomen pushes out as the child attempts to breathe in against a closed airway.

Are they showing any signs of see-saw breathing? This is when the chest is drawn in and the abdomen pushes out as the child attempts to breathe in against a closed airway.

Is the child conscious? If a child is unconscious then the tongue can fall back and occlude the airway and if they vomit then stomach contents can be inhaled.

Is the child conscious? If a child is unconscious then the tongue can fall back and occlude the airway and if they vomit then stomach contents can be inhaled.

Look, listen and feel. Place your cheek next to the child’s mouth and see if you can feel their breath on your cheek, hear any breath sounds or see any movement of the chest. If you can’t see, hear or feel any evidence of breathing start Basic Life Support.

Look, listen and feel. Place your cheek next to the child’s mouth and see if you can feel their breath on your cheek, hear any breath sounds or see any movement of the chest. If you can’t see, hear or feel any evidence of breathing start Basic Life Support.

Airway management (unconscious child)

If a child is unconscious, commence the steps of Basic Life Support, making use of additional techniques mentioned in the Advanced Life Support section if equipment is available.

If a child is unconscious, commence the steps of Basic Life Support, making use of additional techniques mentioned in the Advanced Life Support section if equipment is available.

Airway management (conscious child)

Treat the underlying cause. In cases of anaphylaxis the child will need to be given a dose of intramuscular (IM) adrenaline (see full details on the management of anaphylaxis on page 113). Nebulised adrenaline can be given in cases of croup in order to reduce some of the oedema of the mucosal layer lining the trachea.

Treat the underlying cause. In cases of anaphylaxis the child will need to be given a dose of intramuscular (IM) adrenaline (see full details on the management of anaphylaxis on page 113). Nebulised adrenaline can be given in cases of croup in order to reduce some of the oedema of the mucosal layer lining the trachea.

Don’t upset them. If a child has partial occlusion of their airway but is still conscious, the last thing you want to do is make them start crying as this can make the airway obstruction even worse and cause them to decompensate. Avoid taking bloods or putting in a cannula and certainly don’t try to examine the throat until you have senior colleagues present to help you (including an anaesthetist and an ENT surgeon in case the child totally occludes their airway and needs either intubation or a surgical airway).

Don’t upset them. If a child has partial occlusion of their airway but is still conscious, the last thing you want to do is make them start crying as this can make the airway obstruction even worse and cause them to decompensate. Avoid taking bloods or putting in a cannula and certainly don’t try to examine the throat until you have senior colleagues present to help you (including an anaesthetist and an ENT surgeon in case the child totally occludes their airway and needs either intubation or a surgical airway).

Give oxygen. If the child can tolerate it, give 15 litres of oxygen through a non-rebreathe mask. This means that any air which is getting through to the lungs contains a much higher concentration of oxygen. In very small children who are upset by having a mask fitted, do not force them to wear a mask but instead ask their parents to hold it near their face (this is sometimes referred to as ‘wafting oxygen’).

Give oxygen. If the child can tolerate it, give 15 litres of oxygen through a non-rebreathe mask. This means that any air which is getting through to the lungs contains a much higher concentration of oxygen. In very small children who are upset by having a mask fitted, do not force them to wear a mask but instead ask their parents to hold it near their face (this is sometimes referred to as ‘wafting oxygen’).

Table 5.1 Calculations for commonly used emergency drugs

Figure 5.14 Algorithm of structured approach to management of a sick child. Reproduced from Advanced Life Support Group (2011)Advanced Paediatric Life Support, 5th edn. with permission of John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Top Tip

Top TipB – Breathing

Once you are happy that the child’s airway is secure, you can move on to assessing breathing. In any child who is acutely unwell, put on an oxygen mask if they are able to tolerate it as a matter of course. This is because, regardless of the cause, if they are acutely unwell then they are likely to have an increased oxygen requirement and therefore giving a higher concentration of inhaled oxygen can help increase supply to the tissues.

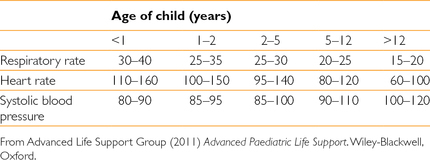

Table 5.2 Normal observation values at different ages

Breathing assessment

What is the child’s respiratory rate? Count the respiratory rate for 1 min and then refer to a table or observation chart to see if this is a normal rate for that child’s age (see Table 5.2). A table of normal observation values for children of different ages, which you can print and attach to your ID badge, is also available at www.wileyhandsonguides.com/paediatrics. Don’t be falsely reassured by a normal respiratory rate if the child is simultaneously tachycardic and looks very unwell; it may be that they are tiring and unable to breathe as quickly. This is a really worrying sign. If the child’s respiratory rate is very low or they are not breathing at all, you will need to ventilate the lungs for them with bag-valve-mask ventilation.

What is the child’s respiratory rate? Count the respiratory rate for 1 min and then refer to a table or observation chart to see if this is a normal rate for that child’s age (see Table 5.2). A table of normal observation values for children of different ages, which you can print and attach to your ID badge, is also available at www.wileyhandsonguides.com/paediatrics. Don’t be falsely reassured by a normal respiratory rate if the child is simultaneously tachycardic and looks very unwell; it may be that they are tiring and unable to breathe as quickly. This is a really worrying sign. If the child’s respiratory rate is very low or they are not breathing at all, you will need to ventilate the lungs for them with bag-valve-mask ventilation.

What are their oxygen saturation levels? If a child has cold peripheries it can sometimes be difficult to get an accurate oxygen saturation reading from their finger. In some cases you may be able to get one from placing the probe on their big toe or ear lobe instead. If you record an oxygen saturation reading in the notes or on the observation chart, you must always record how much oxygen the child was breathing at the time otherwise the reading is meaningless. If a child has oxygen saturations of 93% in room air then you would be much less concerned than if this same reading was taken whilst they were breathing oxygen at 15 L/min, which would be very worrying. Treatment with oxygen should be started if oxygen saturation levels are below 92%. You should also give oxygen, even if the child’s saturation levels are over 92%, if the child is tiring or they have increased work of breathing.

What are their oxygen saturation levels? If a child has cold peripheries it can sometimes be difficult to get an accurate oxygen saturation reading from their finger. In some cases you may be able to get one from placing the probe on their big toe or ear lobe instead. If you record an oxygen saturation reading in the notes or on the observation chart, you must always record how much oxygen the child was breathing at the time otherwise the reading is meaningless. If a child has oxygen saturations of 93% in room air then you would be much less concerned than if this same reading was taken whilst they were breathing oxygen at 15 L/min, which would be very worrying. Treatment with oxygen should be started if oxygen saturation levels are below 92%. You should also give oxygen, even if the child’s saturation levels are over 92%, if the child is tiring or they have increased work of breathing.

Is the child showing any signs of respiratory distress? Signs of respiratory distress include using any of the accessory muscles to assist the child in achieving adequate ventilation.

Is the child showing any signs of respiratory distress? Signs of respiratory distress include using any of the accessory muscles to assist the child in achieving adequate ventilation.

– Head bobbing. In small children and babies their head will bob up and down in time with their breathing if they are working very hard.

– Subcostal recession. This is when you can see an indrawing of the tissues under the lowest rib as the child breathes in.

– Intercostal recession. This is when you can see an indrawing of the soft tissue between the ribs as the child breathes in, making the ribs appear more prominent.

– Sternal recession. In young babies who are having great difficulty breathing, you may see the whole of the sternum being drawn inwards as the child breathes in.

– Nasal flaring. Flaring of the nostrils also indicates respiratory distress. This can be relatively subtle so look carefully.

– Grunting. This is exactly as the name describes, a small grunting noise as the child breathes out which is caused by them partially closing their airway in order to generate a positive pressure in the lungs to prevent airway collapse at the end of expiration. This is a sign of severe respiratory distress and is most often seen in babies.

– Tracheal tug. The trachea looks as if it is being tugged downwards as the child breathes in because they are using the strap muscles of their neck to assist them with breathing. Infants and toddlers have very short necks so you will need to get them to look up so that you can see the trachea.

Is the chest wall moving symmetrically? When you are observing the child’s breathing to look for signs of respiratory distress, also look to check if the child’s chest wall is moving symmetrically. If one side is moving much less than the other this may suggest a pneumothorax, pleural effusion or collapse on that side.

Is the chest wall moving symmetrically? When you are observing the child’s breathing to look for signs of respiratory distress, also look to check if the child’s chest wall is moving symmetrically. If one side is moving much less than the other this may suggest a pneumothorax, pleural effusion or collapse on that side.

Can you hear breath sounds? Listen to the child’s chest and ensure that you can hear good air entry throughout both lungs. Reduced breath sounds on one side could mean a pneumothorax or pleural effusion of that lung. Reduced breath sounds on both sides is an extremely worrying sign as this means that they are failing to get much air at all in and out of the lungs; this is called a ‘silent chest’ and is a sign of life-threatening asthma. For more information on the management of acute asthma see page 115.

Can you hear breath sounds? Listen to the child’s chest and ensure that you can hear good air entry throughout both lungs. Reduced breath sounds on one side could mean a pneumothorax or pleural effusion of that lung. Reduced breath sounds on both sides is an extremely worrying sign as this means that they are failing to get much air at all in and out of the lungs; this is called a ‘silent chest’ and is a sign of life-threatening asthma. For more information on the management of acute asthma see page 115.

Can you hear additional sounds? Is there any wheezing audible? Can you hear bronchial breathing or crackles? If the child has a lot of secretions in the upper airways, these noises can be transmitted so that they sound as if they are coming from the lungs. If this is the case then the sounds should improve or disappear completely for a while after the child coughs and clears their throat.

Can you hear additional sounds? Is there any wheezing audible? Can you hear bronchial breathing or crackles? If the child has a lot of secretions in the upper airways, these noises can be transmitted so that they sound as if they are coming from the lungs. If this is the case then the sounds should improve or disappear completely for a while after the child coughs and clears their throat.

Is there a normal percussion note? Percuss both sides of the chest to assess for any altered percussion note. Hyperresonance may suggest a pneumothorax and dullness may indicate a pleural effusion, consolidation or haemothorax.

Is there a normal percussion note? Percuss both sides of the chest to assess for any altered percussion note. Hyperresonance may suggest a pneumothorax and dullness may indicate a pleural effusion, consolidation or haemothorax.

Does the child look pale or cyanotic? Hypoxia causes pallor of the skin around the lips. If there is evidence of central cyanosis (i.e. a blueish-purple colour to the lips and surrounding skin) then this is a preterminal sign and suggests that the child is imminently about to have a respiratory arrest.

Does the child look pale or cyanotic? Hypoxia causes pallor of the skin around the lips. If there is evidence of central cyanosis (i.e. a blueish-purple colour to the lips and surrounding skin) then this is a preterminal sign and suggests that the child is imminently about to have a respiratory arrest.

Breathing management

Give high-flow oxygen. Give oxygen via a facemask at a sufficient concentration to maintain the oxygen saturations above 92%.

Give high-flow oxygen. Give oxygen via a facemask at a sufficient concentration to maintain the oxygen saturations above 92%.

Support breathing if low respiratory rate. If a child’s respiratory rate is low, they will need to be ventilated using a bag-valve-mask. Start the Basic Life Support protocol and use additional techniques mentioned in the Advanced Life Support section if you have access to appropriate equipment. Put out a crash call (2222) or call the emergency services (999) for any child who is requiring ventilation.

Support breathing if low respiratory rate. If a child’s respiratory rate is low, they will need to be ventilated using a bag-valve-mask. Start the Basic Life Support protocol and use additional techniques mentioned in the Advanced Life Support section if you have access to appropriate equipment. Put out a crash call (2222) or call the emergency services (999) for any child who is requiring ventilation.

Treat urgent respiratory problems.

Treat urgent respiratory problems.

– Tension pneumothorax. This requires immediate decompression. Signs suggestive of a tension pneumothorax include reduced chest movement unilaterally, reduced breath sounds unilaterally, hyperresonance unilaterally, distended neck veins, shock and trachea deviated away from the side of pneumothorax (late sign). To decompress, insert a wide-bore cannula in the midclavicular line in the second intercostal space. Aim just above the top edge of the lower rib in order to avoid the neurovascular bundle that runs along the bottom edge of each rib. You should hear a hissing noise as air is released through the needle. Needle decompression is a temporary emergency measure to relieve a tension pneumothorax but the child will also need insertion of a chest drain to prevent air from accumulating again.

– Wheeze. A brief history is important here to help determine the underlying cause to allow more definitive management (e.g. is this asthma or bronchiolitis or an inhaled foreign body?). However, bronchodilators are likely to be helpful in most situations of wheeze. Try a salbutamol nebuliser (2.5 mg for children under 5 years, 5 mg over 5 years) and consider also giving ipratropium bromide nebuliser (125 micrograms if under 5 years, 250 micrograms if over 5 years).

C – Circulation

Once you have secured the airway, put on oxygen and assessed breathing and dealt with any issues you have found, you can move on to assessing the circulation.

Circulation assessment

Does this child have warm peripheries? Cold hands and feet may be a sign that the child has shut down their peripheral circulation in order to maintain perfusion of their vital organs. If a child has a severely compromised circulation, you may notice that the skin feels cold not just on the feet but also over their lower legs. There are certain kinds of shock that can result in the child having warm peripheries despite having a reduced apparent circulating volume. For more about the different kinds of shock, see below.

Does this child have warm peripheries? Cold hands and feet may be a sign that the child has shut down their peripheral circulation in order to maintain perfusion of their vital organs. If a child has a severely compromised circulation, you may notice that the skin feels cold not just on the feet but also over their lower legs. There are certain kinds of shock that can result in the child having warm peripheries despite having a reduced apparent circulating volume. For more about the different kinds of shock, see below.

What is their capillary refill time? This should be assessed using a central location to give a more accurate assessment of the circulation (as peripheral capillary refill time may be reduced as a normal reaction in a cold room). Press down firmly on the skin over the sternum for 5 sec then remove your finger and count how long it takes for that area of skin to go back to a normal colour (initially the skin should appear blanched when you first remove your finger). A normal central capillary refill time is anything less than 2 sec for the skin to return to a normal colour. Any longer than this suggests a circulatory problem. Don’t forget to document the number of seconds as well as the fact that it is prolonged in order for other people reading it to appreciate the degree of severity.

What is their capillary refill time? This should be assessed using a central location to give a more accurate assessment of the circulation (as peripheral capillary refill time may be reduced as a normal reaction in a cold room). Press down firmly on the skin over the sternum for 5 sec then remove your finger and count how long it takes for that area of skin to go back to a normal colour (initially the skin should appear blanched when you first remove your finger). A normal central capillary refill time is anything less than 2 sec for the skin to return to a normal colour. Any longer than this suggests a circulatory problem. Don’t forget to document the number of seconds as well as the fact that it is prolonged in order for other people reading it to appreciate the degree of severity.

What is their heart rate? Tachycardia can be a sign of circulatory shock. Although a child’s heart rate will be elevated slightly when they are crying, if their pulse is persistently elevated this may suggest a circulatory problem. If a child’s heart rate is less than 60 beats per minute or rapidly falling with associated fall in blood pressure then this is a preterminal sign and you should start Basic Life Support and put out a crash call (2222) or call emergency services (999).

What is their heart rate? Tachycardia can be a sign of circulatory shock. Although a child’s heart rate will be elevated slightly when they are crying, if their pulse is persistently elevated this may suggest a circulatory problem. If a child’s heart rate is less than 60 beats per minute or rapidly falling with associated fall in blood pressure then this is a preterminal sign and you should start Basic Life Support and put out a crash call (2222) or call emergency services (999).

What do their pulses feel like? If you are unable to feel a child’s peripheral pulses or they have weak central pulses then this is a sign of severe shock. A child with sepsis, hypercapnia or some types of congenital structural heart defects may have ‘bounding pulses’ that can be felt very strongly peripherally and centrally.

What do their pulses feel like? If you are unable to feel a child’s peripheral pulses or they have weak central pulses then this is a sign of severe shock. A child with sepsis, hypercapnia or some types of congenital structural heart defects may have ‘bounding pulses’ that can be felt very strongly peripherally and centrally.

What is their blood pressure? Children are very good at maintaining their blood pressure within normal range and can compensate for large volume losses. Do not be reassured by a child who has a normal blood pressure as this is one of the last things to change and if it drops, this is a sign that the child will rapidly deteriorate and cardiac arrest may be imminent. When measuring the child’s blood pressure, it is vital to use the correct size of cuff in order to get an accurate reading. The cuff should be over 80% of the length of the child’s upper arm and the bladder of the cuff over 40% of the child’s arm upper arm circumference.

What is their blood pressure? Children are very good at maintaining their blood pressure within normal range and can compensate for large volume losses. Do not be reassured by a child who has a normal blood pressure as this is one of the last things to change and if it drops, this is a sign that the child will rapidly deteriorate and cardiac arrest may be imminent. When measuring the child’s blood pressure, it is vital to use the correct size of cuff in order to get an accurate reading. The cuff should be over 80% of the length of the child’s upper arm and the bladder of the cuff over 40% of the child’s arm upper arm circumference.

Is there fluid loss or fluid in the wrong place?

Is there fluid loss or fluid in the wrong place?

Fluid loss

Shock as a result of fluid loss is known as hypovolaemic shock. Children with hypovolaemic shock will show signs of ‘cold shock’ (see Table 5.3). Examples of diagnoses that can result in shock due to fluid loss include:

blood loss

blood loss

vomiting and diarrhoea

vomiting and diarrhoea

burns.

burns.

Fluid in the wrong place

Peripheral dilation of blood vessels and increased seepage of fluid from the blood vessels into the tissues can result in shock. These children may have a normal volume of fluid in their bodies but it has either leaked into the soft tissues, meaning that there is insufficient volume left in the blood vessels, or their peripheral blood vessels are all dilated, meaning that they have to use other mechanisms (such as tachycardia) to maintain their cardiac output. These children will show signs of ‘warm shock’ (see Table 5.3). Examples of diagnosis that can result in fluid in the wrong place are:

anaphylaxis

anaphylaxis

sepsis.

sepsis.

Is this compensated or uncompensated shock?

Is this compensated or uncompensated shock?

compensated shock

This means that the child is managing to maintain perfusion to their vital organs despite having underlying shock due to use of their body’s compensatory mechanisms. The body maintains cardiac output by increasing heart rate and the child will also have a raised respiratory rate in order to compensate for the metabolic acidosis that results from shock. Depending on the underlying cause, the child may exhibit different signs of either warm shock or cold shock. See Table 5.3 for signs of warm and cold shock. See Fluid loss versus Fluid in the wrong place above for underlying diagnoses.

Table 5.3 Signs present in warm shock and cold shock

| Warm shock | Cold shock |

| Agitation, drowsiness or unconsciousness Tachycardia Tachypnoea Decreased urine output Clammy, warm extremities Flushed, red skin Flash capillary refill Bounding peripheral pulses Normal/high systolic blood pressure Low diastolic blood pressure Wide pulse pressure | Agitation, drowsiness or unconsciousness Tachycardia Tachypnoea Decreased urine output Cool hands and feet Pale or mottled skin Prolonged capillary refill time Weak peripheral pulses Normal/high systolic blood pressure Normal/high diastolic blood pressure Narrow pulse pressure |

decompensated shock

If a child is showing signs of decompensated shock, put out a paediatric arrest call to get help rapidly. A child who has previously been managing to compensate for shock may tire and decompensate. Decompensated shock can rapidly deteriorate into a respiratory or cardiac arrest without proper intervention so make sure that you get senior input immediately. Signs of decompensated shock include:

hypotension

hypotension

decreased level of consciousness

decreased level of consciousness

anuria

anuria

bradycardia (preterminal sign, start Basic Life Support).

bradycardia (preterminal sign, start Basic Life Support).

Circulation management

Gain access. Try to gain intravenous access if possible but do not spend a long time on multiple attempts. If intravenous access is not proving immediately possible in an acutely unwell child, attempt intraosseous access instead. See Chapter 6 – Practical Procedures, for details.

Gain access. Try to gain intravenous access if possible but do not spend a long time on multiple attempts. If intravenous access is not proving immediately possible in an acutely unwell child, attempt intraosseous access instead. See Chapter 6 – Practical Procedures, for details.

Take blood samples. As you gain intravenous or intraosseous access, draw back on the cannula or intraosseous needle to obtain a blood sample. If you have taken a sample from an intraosseous needle, this is bone marrow rather than blood and can only be used for restricted tests and never in a blood gas machine. See Chapter 6 – Practical Procedures, for more details or call your hospital laboratory for advice.

Take blood samples. As you gain intravenous or intraosseous access, draw back on the cannula or intraosseous needle to obtain a blood sample. If you have taken a sample from an intraosseous needle, this is bone marrow rather than blood and can only be used for restricted tests and never in a blood gas machine. See Chapter 6 – Practical Procedures, for more details or call your hospital laboratory for advice.

If shocked, give a bolus of 0.9% saline. The volume of fluid to give will depend on the underlying cause. In most cases of shock a bolus of 20 mL/kg of 0.9% saline is appropriate, repeated as necessary until clinical signs improve. If you suspect an underlying diagnosis of diabetic ketoacidosis, hyponatraemia or heart failure you should give a bolus of 10 mL/kg of 0.9% saline.

If shocked, give a bolus of 0.9% saline. The volume of fluid to give will depend on the underlying cause. In most cases of shock a bolus of 20 mL/kg of 0.9% saline is appropriate, repeated as necessary until clinical signs improve. If you suspect an underlying diagnosis of diabetic ketoacidosis, hyponatraemia or heart failure you should give a bolus of 10 mL/kg of 0.9% saline.

Top Tip

Top TipD – Disability

Once you have managed airway, breathing and circulation and are happy that these are stable for now, you can move on to assess disability. This means assessing neurological function and has several different components.

Disability assessment

What is this child’s conscious level? The Glasgow Coma Scale is often used in adults but less frequently used in children, apart from in severe head injury (see Table 5.4 for age-specific Glasgow Coma Scale). In most paediatric emergency situations, the AVPU assessment tends to be used instead as part of the initial assessment. AVPU stands for:

What is this child’s conscious level? The Glasgow Coma Scale is often used in adults but less frequently used in children, apart from in severe head injury (see Table 5.4 for age-specific Glasgow Coma Scale). In most paediatric emergency situations, the AVPU assessment tends to be used instead as part of the initial assessment. AVPU stands for:

– Alert

– responds to Voice

– responds only to Pain

– Unresponsive.

Any child who has a conscious level of P or U will be unable to protect their own airway and intubation should be considered. To assess response to pain, either squeeze the child’s trapezius muscle firmly or apply pressure to the bony supraorbital area, just below the inner aspect of the eyebrow (being careful not to press on the eyeball).

Are their pupils of equal size and reactive? Check to make sure that the pupils are the same size as each other and both respond to light. Pupils of markedly different sizes or that fail to constrict when you shine a light in them may indicate a serious underlying brain disorder.

Are their pupils of equal size and reactive? Check to make sure that the pupils are the same size as each other and both respond to light. Pupils of markedly different sizes or that fail to constrict when you shine a light in them may indicate a serious underlying brain disorder.

What is the child’s posture? decorticate and decerebrate posturing can both indicate severe underlying brain pathology. decorticate posturing is when the child is stiff and has their arms flexed and their legs extended. decerebrate posturing is when the child is stiff and has both their arms and legs extended. These postures can sometimes be mistaken for seizures. See Fig. 5.15 for illustrations of decorticate and decerebrate posturing.

What is the child’s posture? decorticate and decerebrate posturing can both indicate severe underlying brain pathology. decorticate posturing is when the child is stiff and has their arms flexed and their legs extended. decerebrate posturing is when the child is stiff and has both their arms and legs extended. These postures can sometimes be mistaken for seizures. See Fig. 5.15 for illustrations of decorticate and decerebrate posturing.

Table 5.4 Glasgow Coma Scale for Children

| Glasgow Coma Scale (>4 years) | Glasgow Coma Scale (<4 years) |

| Eye opening 4 Spontaneously 3 To verbal stimuli 2 To pain 1 No response to pain | Eye opening 4 Spontaneously 3 To verbal stimuli 2 To pain 1 No response to pain |

| Best motor response 6 Obeys verbal command 5 Localises to pain 4 Withdraws from pain 3 Abnormal flexion to pain (decorticate) 2 Abnormal extension to pain (decerebrate) 1 No response to pain | Best motor response 6 Spontaneous or obeys verbal command 5 Localises to pain or withdraws to touch 4 Withdraws from pain 3 Abnormal flexion to pain (decorticate) 2 Abnormal extension to pain (decerebrate) 1 No response to pain |

| Best verbal response 5 Oriented and converses 4 Disoriented and converses 3 Inappropriate words 2 Incomprehensible sounds 1 No response to pain | Best verbal response 5 Alert; babbles, coos words to ability 4 Fewer than usual words, spontaneous irritable cry 3 Cries only to pain 2 Moans to pain 1 No response to pain |

< div class='tao-gold-member'>