39 Common Injuries

Principles of Injury Control

Principles of Injury Control

Passive injury prevention is the implementation of safety measures that do not require caregivers to constantly change their behavior to make the environment safer for their children. This prevention strategy is the most effective intervention and includes modification of everyday items in the child’s environment. Examples include the use of child-resistant caps on medicines and cleaning products, and safety designs in toys. Other safety implementations include environmental modification such as the use of smoke and carbon monoxide detectors, safe roadway design to reduce traffic volume and speed in residential neighborhoods, window locks, and firearm safety locks. Providers can advocate for local and national prevention strategies and support such programs as the Safe Kids USA campaign. They can also play a key role by supporting injury prevention legislation or initiatives. Public and consumer awareness is crucial for successful prevention programs.

Approach to Trauma

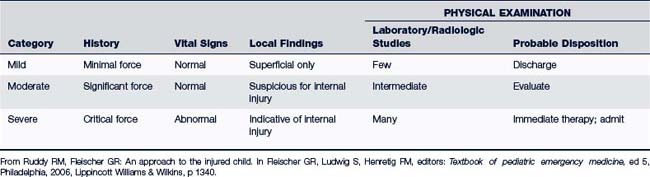

Three main components essential in the management of an injured child include history, mechanism of the injury, and a thorough physical examination. If the injury is life-threatening, or there has been any deterioration in the child’s condition, a trauma severity assessment must immediately be performed. Primary assessment of the injured child should occur within the first 5 minutes of initial contact and includes the assessment of the airway, breathing, circulation, evaluation of vital signs, obtaining a brief history (allergies, medications, past medical history, and events surrounding the injury), and rapid assessment of essential organ status. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation must be initiated if indicated. Once the patient is stabilized, a secondary assessment should include complete physical examination and laboratory and radiographic studies as indicated. Assessment of the patient’s vital signs, physical exam, and laboratory tests should be repeated as indicated based on the injury and initial study results. The definitive care phase includes stabilization of local injuries and preparation of the patient and family for transport to the ED if necessary (Table 39-1).

Common Pediatric Injuries

Common Pediatric Injuries

Trauma to the Skin and Soft Tissue

Management

Appropriate first-aid care is important to prevent infection. Most abrasions of the skin can be managed at home unless the abrasion is deep, involves a large area, is associated with severe pain, or has a significant amount of dirt, grime, tar, or a foreign body in the wound. A child who is immunocompromised may need to be seen due to increased risk of infection.

Management of an abrasion includes the following:

• Thoroughly cleanse the wound. The area can be scrubbed with soap or an antibacterial cleanser using a wet gauze or soft surgical nail brush. Gentle irrigation with copious amounts of water or normal saline (300 to 1000 mL) is the preferred method to thoroughly cleanse a wound and prevent infection. Povidone-iodine, alcohol, and peroxide should not be used on open wounds. If dirt or dark-colored matter is not adequately removed, new skin may grow over the particles, resulting in a permanent tattoo. A secondary infection may occur as well if all debris is not removed from the wound. Remove pieces of loose skin with a sterile scissors and remove foreign particles with tweezers. If tar particles are present, rub the wound area with petrolatum, and then repeat normal saline or water irrigation.

• Small abrasions can be left open to the air or may require a small bandage.

• Cover larger abrasions with a sterile nonadherent dressing. Double antibiotic ointment such as bacitracin/polymyxin B may be applied, especially to abrasions of the elbows or knees to prevent cracking or reopening of the wound because of constant movement and stretching of the joints.

• Protect abrasions of the hands, feet, or areas overlying joints from friction and dirt until a protective dry scab is formed.

• Instruct the caregiver to wash the abrasion at least every 24 hours and reapply the dressing and antibiotic ointments until a protective dry scab is formed. Instructions regarding the signs and symptoms of infection should also be provided.

• Tetanus prophylaxis should be administered if the wound is significant. The use of Tdap is the preferred vaccination for children 10 to 11 years of age and older (see Chapter 23).

Puncture Wounds

Clinical Findings

History

• Date and time of injury and history of wound care provided at time of injury and thereafter

• Identification of and the type and estimated depth of object penetration. If it is not known what object penetrated the skin, the likelihood of an imbedded foreign body is high.

• Location and condition of the penetrating object. Was the object clean or rusty, jagged or smooth?

• Whether all or part of the foreign object was removed

• Type and condition of footwear that was being worn (pertinent to injuries to the foot) or if the child was barefoot

• Immunization status for tetanus coverage (see Chapter 23)

• Presence of any medical condition that increases the risk for infectious complications

Physical Examination

Examination findings consistent with cellulitis include:

• Localized pain or tenderness, swelling, and erythema at the puncture site (may be more obvious at dorsum of the foot for plantar puncture wounds)

• Pain with flexion or extension of the extremity involved

• Decreased ability to bear weight

• For plantar puncture wounds, pain along the plantar aspect of the foot during extension or flexion of the toes may indicate deep tissue injury.

Examination findings consistent with osteomyelitis-osteochondritis include:

• Extension of pain and swelling around the puncture wound and to the adjacent bony structures

• Exquisite point tenderness over the bone

Examination findings consistent with pyarthrosis (septic arthritis) include:

Diagnostic Studies

• Plain film radiograph should be ordered if any of the following are true:

There is tremendous amount of pain at the puncture site with localized tenderness or questionable mass underneath the skin surface (Baddour, 2009).

There is tremendous amount of pain at the puncture site with localized tenderness or questionable mass underneath the skin surface (Baddour, 2009). There was penetration of a joint space, bone or growth cartilage, or the plantar fascia of the foot.

There was penetration of a joint space, bone or growth cartilage, or the plantar fascia of the foot.• Most metal and glass foreign bodies can be seen on a plain radiograph. However, if the foreign object is not radiopaque or if the x-ray is negative despite suspicion of foreign object in the wound, computed tomography (CT), ultrasound, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are useful diagnostic tools (Buttaravoli, 2007).

• Bone scans are sensitive, but not specific for osteomyelitis. Radiographs are specific, but findings for osteomyelitis are noted late. Clinical examination and laboratory studies and imaging should be considered early in the diagnosis of osteomyelitis (Polousky and Eilert, 2009).

• A complete blood count (CBC) and blood culture may be needed. An elevation in the white blood cell count might indicate infection.

• An erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP) are nonspecific inflammatory markers and are helpful in the diagnosis and management of bony inflammation and infection.

• A wound culture is indicated prior to starting antibiotics if the wound appears infected.

Management

• Irrigate with copious amounts of normal saline for puncture wounds caused by small, clean, slender nonrusty objects (e.g., thumbtack or needle) after confirmation of complete removal of the intact object, and when signs of infection are absent.

• Larger puncture wounds require profuse irrigation. Wound debridement may also be necessary. A No. 10 scalpel may be used to gently shave off the cornified epithelium surrounding the puncture wound to aid in the removal of debris that collected around the point of entry of the puncture wound. If debris is found in the wound, gently slide the plastic sheath of an over-the-needle catheter down the wound track and move the catheter sheath in and out while irrigating with copious amounts of normal saline until debris no longer flows from the wound. A local anesthetic agent may be necessary for debridement and irrigation procedures.

• Obtain imaging studies as indicated for proper management of the puncture wound. If imaging studies demonstrate that the foreign object has invaded bone, growth cartilage, or a joint space, refer the child immediately to an orthopedic surgeon. Always suspect a retained foreign object if the puncture wound is infected, the infection is not responding to antibiotic therapy, or if pain or aching of the injured site is still present weeks after the injury. In order to prevent a catastrophic outcome, wounds that are deep or highly contaminated should be referred to an orthopedic surgeon so that debridement can take place in an operating room (Buttaravoli, 2007).

• Following careful wound cleansing, the wound can be covered with a simple bandage. Deeper wounds that require more extensive exploration should have a small sterile wick of iodoform gauze placed in the wound tract in order to keep the edges open, thus aiding in granulation tissue growth and wound healing. Remove the gauze 2 to 3 days after placement (Selbst and Attia, 2010).

• Children with simple, uncomplicated puncture wounds do not need antibiotics; however, if there are signs of infection, the puncture is the result of a cat bite, or if the wound is deep or contained debris, antibiotics should be part of the treatment plan. Appropriate antibiotics for puncture wounds include amoxicillin clavulanate or cephalexin. Clindamycin should be used when children are allergic to penicillins. Plantar puncture wounds require ciprofloxacin. If methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) is cultured from the wound or pus is present at the puncture site, then trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX) or clindamycin is recommended until sensitivities are known. All antibiotics should be prescribed for 7 to 14 days depending on severity of infection (Baddour, 2009).

• Schedule a recheck appointment within 48 hours. If pain, erythema, and swelling have not improved or symptoms have worsened within the first 48 hours of outpatient treatment, hospitalization and intravenous antibiotics are indicated (Baddour, 2009).

• Treatment for severe infections secondary to puncture wounds such as septic arthritis and osteomyelitis includes surgical debridement and parenteral antibiotics (Hosalkar et al, 2007).

• Tetanus prophylaxis is indicated if it has been more than 5 years since the last tetanus vaccine or if the date of the last tetanus vaccine is unknown. Consider passive immunization with tetanus immune globulin (TIG) or initiation/continuation of a primary tetanus series (DTaP, Tdap, or Td as appropriate) for children who may have never been immunized or are behind in their vaccinations (see Chapter 23).

Patient and Parent Education

Home care management for a puncture wound includes:

• No weight bearing for 3 or 4 days if the injury was a puncture to the foot

• Warm compresses to the affected area three or four times daily

• Close observation for signs and symptoms of infection and if infection is suspected, rapid re-evaluation is necessary. Further evaluation is required if a puncture wound continues to cause localized or spreading pain or discomfort.

Ingrown Toenails and Nail Hematoma

Management

Pack cotton under the nail edge to elevate the nail, and educate the patient to repack the cotton daily to prevent infection.

Pack cotton under the nail edge to elevate the nail, and educate the patient to repack the cotton daily to prevent infection. Epsom salt mixed with warm-water foot soaks for 20 minutes, three times a day. Keep the foot or affected toenail clean and dry. Encourage frequent elevation of the affected toe as well as minimal activity to aid in healing.

Epsom salt mixed with warm-water foot soaks for 20 minutes, three times a day. Keep the foot or affected toenail clean and dry. Encourage frequent elevation of the affected toe as well as minimal activity to aid in healing. Educate about the importance of clipping nails straight across with extension of toenail just over the edge of the nailbed. Properly fitting shoes are also important.

Educate about the importance of clipping nails straight across with extension of toenail just over the edge of the nailbed. Properly fitting shoes are also important. For persistent ingrown toenails with or without infection, consider a referral to a podiatrist for partial or complete toenail removal.

For persistent ingrown toenails with or without infection, consider a referral to a podiatrist for partial or complete toenail removal. Make one or more holes in the area of the nail hematoma with either a portable heat cautery device or the end of an untwisted heated-to-red paperclip (heated to melt the nail). Ensure the holes are large enough to drain the hematoma. Remove the cautery device immediately after creating a hole to ensure that the underlying tissue is not cauterized subsequently blocking the drainage of fluid.

Make one or more holes in the area of the nail hematoma with either a portable heat cautery device or the end of an untwisted heated-to-red paperclip (heated to melt the nail). Ensure the holes are large enough to drain the hematoma. Remove the cautery device immediately after creating a hole to ensure that the underlying tissue is not cauterized subsequently blocking the drainage of fluid. Home care includes educating patient and parent to monitor for signs of infection (increased redness, swelling, pain, or purulent drainage) and to return for further care if infection is suspected. Instruct soaking of affected nailbed three times per day with antibacterial soap until the drainage has stopped and the underlying skin has healed.

Home care includes educating patient and parent to monitor for signs of infection (increased redness, swelling, pain, or purulent drainage) and to return for further care if infection is suspected. Instruct soaking of affected nailbed three times per day with antibacterial soap until the drainage has stopped and the underlying skin has healed.Lacerations

Clinical Findings

History

Key questions when assessing a laceration include:

• How did the injury happen? Determining the mechanism of injury is essential in identifying the potential extent of tissue damage, the presence of contaminants, and the possible presence of a foreign body, such as dirt, debris, glass, and splinters.

• How long ago (number of hours) did the injury occur? Length of time since injury is a critical factor to consider and can influence the treatment plan for the patient.

• Does the child have allergies to antibiotics or anesthetics?

• What is the child’s tetanus immunization status? Is there a need for further immunization?

Physical Examination

Key points in the examination of a laceration include:

• Perform a neurovascular examination, including evaluation of pulses, motor function, and sensation distal to the laceration.

• Evaluate the range of motion, especially with wounds involving the distal forearm, wrist, and hand due to the high potential for tendon injury.

• Determine whether the wound edges approximate and note the degree of tension at the wound site.

Management

The steps in wound management are summarized as follows (Selbst and Attia, 2010):

1. Decision to close the wound. Compared with adults, children are less likely to get wound infections. In fact, the infection rate from sutured lacerations in children is 2%. Most wounds may be closed using a primary wound closure (i.e., bringing the edges of the skin together, known as “approximation”) as soon after the injury as possible to speed healing, prevent infection, and improve the cosmetic result. Delayed closure increases the risk of infection. Some researchers suggest a “golden period” for wound closure of 6 hours. However, wounds considered low risk for infection, such as a clean knife wound to an extremity, can be closed even 12 to 24 hours after the injury. Other guidelines to consider in wound closure include the following:

2. Anesthesia. Appropriate use of local anesthetic and conscious sedation is essential for successful repair of lacerations in children. Proper wound care includes wound exploration and careful cleansing, both painful procedures made worse by fear and anxiety. Infiltration of the wound with local anesthetic, such as 1% lidocaine with or without epinephrine (depending on location of laceration) can also help control bleeding. LET (lidocaine, epinephrine, tetracaine), LAT (lidocaine, adrenaline, tetracaine), and TAC (tetracaine, adrenaline, cocaine) are topical solutions placed on minor wounds 20 to 30 minutes prior to cleansing or repair procedures to help with pain management and to control bleeding. Topical solutions such as these cannot be used on eyes, ears, nose, fingers, genitals, or toes. Texts are available that address procedures in primary care that include excellent information on local anesthetic and wound closure. Attendance at workshops that focus on wound management is also helpful.

3. Hair. Hair near the wound usually creates minimal difficulty during repair and generally does not need to be removed. In any case, hair should not be shaved because to do so can damage hair follicles and increase the risk of infection. Instead, the hair should be clipped with scissors when necessary. Alternatively, petroleum jelly can be used to keep unwanted scalp hair away from the wound while suturing. Eyebrow hair should not be removed because this may lead to abnormal or slow regrowth.

4. Wound cleansing. Chlorhexidine or povidone-iodine surgical scrub preparations may be used to clean the skin surrounding the wound but are not recommended for use in the wound itself. Other agents not recommended for wound cleansing include hydrogen peroxide and alcohol. These agents may be irritating to tissues, causing slow healing times, and may increase infection by damaging white blood cells. The preferred method of wound cleansing is irrigation to reduce bacterial contamination and prevent subsequent infection. Normal saline or tap water is a safe and cost-effective choice for irrigation (Garcia-Gubern et al, 2010). A good rule of thumb for volume needed for saline irrigation is to use 50 to 100 mL of normal saline per centimeter of the wound or laceration. More solution may be needed if the wound is unusually large or contaminated. A large irrigating syringe (20 to 50 mL) is needed to provide enough force to cleanse the wound. A splash guard attached to the syringe is recommended to reduce splatter during irrigation. Scrubbing the wound should be reserved only for particularly “dirty” wounds when irrigation does not remove contaminants completely. Forceps may also be required to remove foreign debris from the wound when saline irrigation is unsuccessful. It is important to remove all foreign debris to decrease infection risk and prevent tattooing of the skin.

5. Exploration of the wound. The wound must be explored for presence of foreign bodies, deep tissue layer damage, injury to nerve or blood vessel, or joint involvement. It is imperative that the depth of the wound be determined. Wound probing is done with a cotton-tipped swab, a hemostat, or a needle holder. Deep lacerations should be referred to an ED for layered closure. If tendon injury is suspected or if bone is exposed, referral to an orthopedist is the standard of care.

6. Wound debridement. Gentle removal of unattached loose tissues may be done with sterile instruments. Debridement is advantageous because it helps to remove contaminant from the wound and creates more approximated wound edges. The approximation of wound edges allows for easier wound repair and cosmetic acceptability after the wound is healed for the patient. Although it is helpful to excise necrotic skin, excessive trimming of irregular lacerations should not be attempted. Excessive removal of tissue can create a defect that is difficult to close or that may increase tension at the wound margin, making scarring more likely.

7. Wound closure. Several methods are available for wound closure.

8. Dressing. A simple repaired laceration may be covered with an adhesive bandage. For more complex repaired injuries, dress the wound with nonadherent gauze for the first layer followed by a second layer of plain gauze if needed and secured in place with adhesive tape or elasticized gauze (tubular net bandage).

9. Immunization. Give tetanus booster or tetanus immunoglobulin as indicated.

10. Antibiotic controversy. Antibiotic prophylaxis of clean wounds is not indicated. Its use in contaminated wounds may be helpful, but careful wound cleaning with extensive irrigation followed by prompt wound closure (when indicated) are the most effective safeguards in preventing infection.

11. Suture and staple removal. Remove sutures or staples depending on their location (a useful guide can be found in Table 39-3).

TABLE 39-2 Advantages and Disadvantages of Common Wound Closure Techniques

| Technique | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| Suture | Time honored Meticulous closure Greatest tensile strength Lowest dehiscence rate | Requires removal Requires anesthesia Greatest tissue reactivity Highest cost Slowest application Highest risk of needlestick |

| Staples | Rapid application Low tissue reactivity Low cost Low risk of needlestick | Less meticulous closure May interfere with imaging techniques |

| Tissue adhesive | Rapid application Patient comfort Resistant to bacterial growth No need for removal Low cost Low or no risk of needlestick | Lower tensile strength than sutures Dehiscence over high-tension areas Not useful on hands |

| Surgical tape | Least reactive Lowest infection rate Rapid application Patient comfort Low cost No risk of needlestick | Frequently falls off Lower tensile strength than sutures Highest rate of dehiscence Requires use of toxic adjuncts to adhere to skin Cannot be used in areas with hair Cannot get wet |

From Sullivan DM: Soft tissue injury and wound repair. In Strange GR, Ahrens W, Schafermeyer R, et al, editors: Pediatric emergency medicine, ed 3, New York, 2009, McGraw-Hill, p 335.

TABLE 39-3 Suture and Staple Removal Guide

| Location of Sutures | Length of Time Before Removal |

|---|---|

| Facial | 3-5 days |

| Scalp | 7-10 days |

| Upper extremity | 7-10 days |

| Trunk | 10 days |

| Lower extremity | 8-10 days |

| Over a joint | 10-14 days |

Patient and Parent Education

• Patient can briefly shower 48 hours after sutures are in place without worrying about the risk of possible infection. However, dry the area well and keep it dry at all times.

• Note signs and symptoms of infection that warrant an early recheck (redness, swelling, discharge, increasing pain).

• Give instructions about cleansing and bandaging the wound; instructions vary based on severity of the wound. For surgical tape and topical skin adhesive, do not use topical antibiotic ointment because it will remove the adhesive.

• List any restrictions on activities.

Burns

Description

• Superficial, or first-degree, burns involve only the epidermis. The skin is erythematous, inflamed, and painful, but there are no blisters. Superficial burns typically heal in 3 to 7 days, have little risk of scarring, and require only symptomatic treatment. A common example of a superficial burn is a sunburn.

• Partial-thickness, or second-degree, burns involve the epidermis and the dermis to a variable degree. Superficial partial-thickness burns involve less than 50% of the dermis, and deep partial thickness burns involve more than 50% of the dermis (Tsarouhas and Agosto, 2008). The dermal appendages are always preserved and provide a source for regeneration.

Superficial partial-thickness burns are red, very painful, mottled, moist, and blistered. These burns usually heal in 7 to 14 days, and scarring may occur.

Superficial partial-thickness burns are red, very painful, mottled, moist, and blistered. These burns usually heal in 7 to 14 days, and scarring may occur. Deep partial-thickness burns appear pale and yellow. These burns are less painful and weepy than superficial partial thickness burns. Deep partial-thickness burns take longer to heal (3 weeks) and scarring is more likely to occur.

Deep partial-thickness burns appear pale and yellow. These burns are less painful and weepy than superficial partial thickness burns. Deep partial-thickness burns take longer to heal (3 weeks) and scarring is more likely to occur.• Full-thickness or third-degree burns are major thermal injuries in which the epidermis and dermis are completely destroyed. The skin appears whitish (a waxy white appearance) or leathery. The surface is dry and nontender to palpation. Fluid losses can be profound with this degree of burn. Full-thickness burns usually require skin grafting, are associated with permanent scarring, and take several weeks to heal.

• Full-thickness burns with extension into deep tissues, also known as fourth-degree burns, involve destruction and/or extensive injury of muscle, fascia, nerves, tendons, vessels, and bone. They typically require surgical intervention and skin grafting.

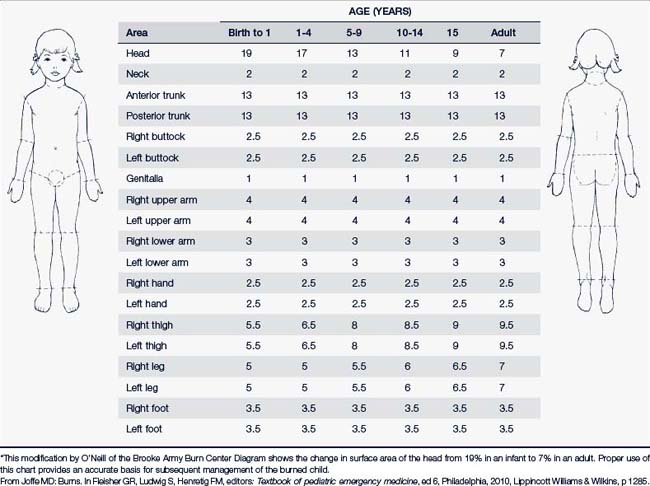

Burns involving large surfaces of the body generally vary as to their degree of depth. Burn wounds are dynamic, and the effect of dermal ischemia (affected by infection, exposure, and dehydration) may not be readily apparent at first. Their depth can also change from day to day. The percentage of body surface area (BSA) and the part(s) of the body affected are also key factors to determine treatment, disposition, and prognosis (Table 39-4). Multiple methods have been devised to estimate the BSA affected. For example, the area covered by a child’s palm (from wrist crease to finger crease), also called the “rule of the palm,” is considered to represent 1% of total BSA and may be used for estimating the extent of small burns covering less than 10% of BSA (Antoon and Donovan, 2007). Free software to calculate BSA in pediatric burn victims is available at http://www.sagediagram.com/.

• Partial-thickness burns involving 10% to 25% of BSA

• Partial-thickness burns, or superficial burns of concern involving the hands and feet, genitalia, perineum; circumferential burns and burns overlying joints

• Full-thickness burns involving 2% to 15% of BSA

• Chemical burns, electrical burns (including lightning injury), inhalation injury

• Burns associated with another injury (e.g., motor vehicle accident) or in a child with a preexisting medical disorder

• Inability of caregiver to care for a child with a burn at home or suspicion of child abuse or neglect

Children with any sign of airway compromise should immediately be placed on 100% oxygen and sent to the hospital for further care and management. Airway complications and inhalation injuries should be suspected if there is loss of consciousness, presence of facial burns, burns over nasal passages or oral cavity, hoarseness, change in voice, or presence of cough or wheezing (Antoon and Donovan, 2007).

Clinical Findings

History

The following information should be obtained:

• Description of how the burn occurred, including agent of injury and length of time agent was in contact with the skin, circumstances surrounding the injury, when it occurred, and likelihood of other injuries, such as trauma or smoke inhalation

• Initial and subsequent treatment of the burn

• Previous history of burn injuries

• Other current medical problems, medications, allergies, and tetanus status

• Suspicion of child abuse if the injury does not match the history and mechanism described (see Chapter 17).

Physical Examination

The physical examination should begin by conducting a primary assessment of the airways. The most common cause of death during the first hour after a burn injury is respiratory impairment. Inhalation injury produces upper airway edema that can proceed with alarming speed to complete airway obstruction. Inhalation injury should be suspected if there is hoarseness, wheezing, cough, rales, singed nasal hairs, carbonized sputum, cyanosis, or altered mental status. Inhalation injury may also be associated with facial or neck burns. In such cases immediate emergency intervention (paramedics and immediate transport to the ED) is warranted. Once the patient is stable, a thorough physical examination requires the following determinations:

• Percentage of BSA affected (see Table 39-4)

• Type of burn and associated injuries

• Distribution and pattern of the burn with particular concern for circumferential burns to the thorax that may cause poor chest expansion and declining oxygen saturation

• Burn depth—classified as superficial, partial thickness, or full thickness

• Assessment of the vascular status of extremities

Diagnostic Studies

• A CBC is indicated to establish baseline levels. The hematocrit is often elevated secondary to fluid loss. Initial elevation of the white blood cell count is most always secondary to an acute phase reaction, but later may be an indicator of infection.

• A basic metabolic panel may reveal elevated potassium due to cell breakdown. Blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and creatinine are used to assess renal function and tissue perfusion.

• A urinalysis, particularly the specific gravity, helps determine hydration status, and presence of myoglobin may suggest acute tubular necrosis secondary to muscle tissue destruction and breakdown.

• Baseline clotting studies and typing and crossmatching may be indicated if there is associated trauma or if surgical intervention, such as grafting, is considered.

• Pulse oximetry, arterial blood gases, carboxyhemoglobin (for inhalation or suspected inhalation injury), and chest radiographs are indicated if there is airway involvement or vascular instability.

• Cardiac monitoring may be needed for electrical burn injury and as indicated.

• Culturing of critical burn wounds may need to be done weekly or more frequently if infection develops.

Differential Diagnosis

Chapter 17 discusses intentional burn injuries resulting from child abuse. Scalded skin syndrome caused by staphylococcal infection can cause skin exfoliation, but the clinical presentation clearly differentiates it from an accidental burn injury. Management is similar to that used for burn management.

Management

Most children with major burns require treatment in the hospital setting and management by a burn specialist team. Electric and chemical burns also require hospitalization for observation and management. Children with a burn injury associated with inhalation injury, fractures, suspicion of abuse, uncertainty of follow-up by the parent, or severe pain should also be admitted. The outpatient treatment of minor burns is an option only for superficial burns (first degree) and partial-thickness burns (second degree) to less than 10% of BSA. Referral and consultation with a burn specialist should be made depending on severity and location of the burn. Box 39-1 outlines the primary care management of superficial and partial-thickness burns. Partial-thickness burns covering greater than 10% of BSA, full-thickness burns covering more than 2% of BSA, and any partial- or full-thickness burns of the face, hands, feet, perineum, or genitalia should be referred for hospital management by burn specialists (Reddy and Parke Maier, 2009; Tsarouhas and Agosto, 2008).

BOX 39-1 Management of Superficial and Partial-Thickness Burns in the Primary Care Setting

1. Maintain proper nutrition and hydration to enhance healing.

2. Management of superficial burns (Sheridan, 2008):

3. Management of superficial partial-thickness burns (Antoon and Donovan, 2007):

Patient and Parent Education

The following points are important components of patient and parent education:

• Emphasize use of sunscreen protection to prevent sunburn. This is also very important for skin that is recovering from a burn because the skin is prone to hyperpigmentation from sunlight for up to a year following the burn injury. All skin that has been burned should be protected from sun for at least 12 months. Encourage parents to avoid sun exposure as much as possible and to use a sunscreen with a sun protection factor (SPF) of 30 (or higher) if sun exposure is unavoidable.

• Discuss home and environmental safety issues related to burn prevention at health maintenance visits. Effective strategies include the use of anti-scald temperature devices for the tub and shower, turning pot handles, making the area around the stove a “kid-free zone,” avoiding carrying children with lit cigarettes or hot liquids in hand, keeping appliance cords away from counter edges, installing working smoke detectors, changing the batteries at the start and end of daylight saving time, and keeping fire extinguishers in homes and cars (Quinlan et al, 2010).

• Reinforce safety issues after a burn injury has occurred (e.g., scald prevention, use of smoke detectors, safekeeping of matches and cigarette lighters, safe use of electric cords and outlets).

• Teach first-aid measures for burns (e.g., submerge minor burned area in tepid water; do not use butter, margarine, and oil-based creams and lotions; rinse chemical burns in cold water, and flush skin thoroughly for at least 20 minutes).

• Inform parents of serious or long-term consequences of burns: frequent and significant sunburns during early childhood can predispose to skin cancers in later life; electric burns cause thermal injury to skin [contact burn]; if an arc is created and there is passage of electrical current through the body, there is a potential for cardiac dysrhythmias and neurologic impairment following the burn.

• Inform parents that the extent of scarring is difficult to predict with certainty; that scarring depends on depth of the burn, length of time needed for healing, whether grafting was done, and the child’s age and skin color; and that scars remain immature for the first 12 to 18 months and go through color and texture changes as the child grows. Most minor scald injuries from hot liquids heal quickly with little or no scarring.

Contusions and Hematomas

Clinical Findings

Physical Examination

The following should be determined:

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree