22 Common Fractures

Each age group has typical mechanisms of injury and common fractures. When evaluating newborns and infants with injuries, one should maintain a high index of suspicion for nonaccidental trauma because this is a leading cause of fracture in this age group (see Chapter 12). Injuries in toddlers and school-aged children most often result from falls. During adolescence, injuries become similar to those of adults and are often sustained in sports or through high-energy mechanisms, such as motor vehicle collisions.

Fracture Description

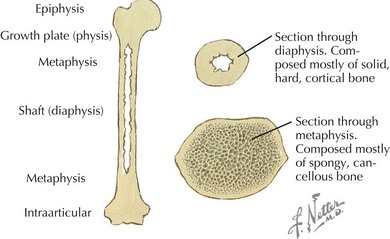

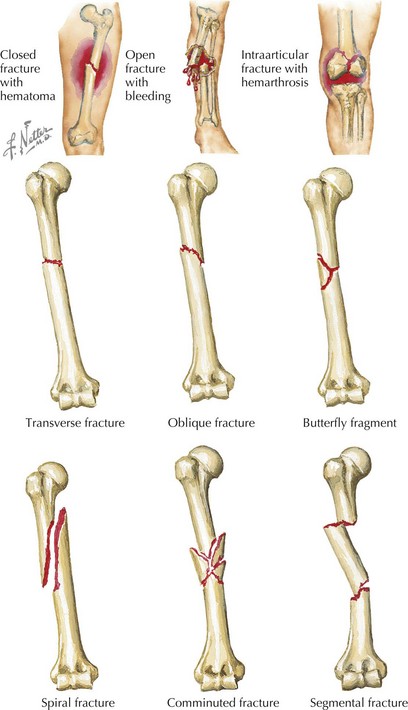

After a fracture has been identified, to effectively communicate with orthopedic consultants and other health care providers, it is important to use fracture nomenclature so that appropriate decisions can be made regarding management and treatment. Consultants should always be made aware of the patient’s neurovascular status. Radiographic interpretation of the fracture should include the type of image; anatomic location (Figure 22-1); whether it is complete or incomplete, open or closed, and intra- or extraarticular; and the presence of physeal (growth plate) disruption, displacement, angulation, shortening, or comminution (Figure 22-2).

Fractures that extend across the width of a bone are complete fractures, and those that do not extend all the way across are incomplete fractures. Incomplete fractures are more common in children than adults and are described in more detail below. Complete fractures can be further characterized according to their orientation as transverse fractures (those running at right angles to the long axis of the affected bone), oblique fractures (those that cross the shaft at an angle), and spiral fractures (fractures in which the break is helical). Any fracture that divides the bone into more than two separate segments is said to be comminuted (see Figure 22-2).

Perhaps the most important feature of a fracture is the distinction between an open and closed fracture (see Figure 22-2). In open fractures, the overlying skin is disrupted, and the fracture communicates with the outside environment, thus leading to increased risk of infection. Open fractures are an orthopedic emergency and necessitate operative repair.

Common Fracture Types in Children

Physeal Fractures

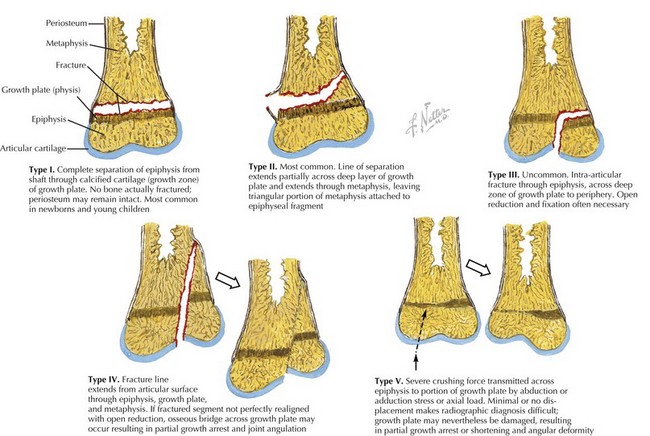

Fractures involving the physis occur frequently in children and account for up to 20% of all pediatric fractures. Although several classification systems for the description of physeal fractures exist, the Salter-Harris classification system is the most widely used. This classification system, based on the radiographic appearance of the fracture, describes the degree of involvement of the physis, epiphysis, metaphysis, and joint and has both prognostic and therapeutic implications (Figure 22-3).

Greenstick Fractures

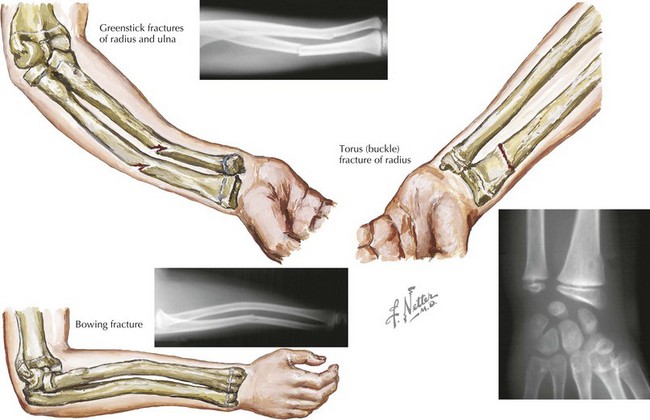

Greenstick fractures are the most common fracture pattern in children. They describe an incomplete fracture of cortex in which the fracture line does not extend completely through the width of the bone. Depending on the degree of angulation, reduction by an orthopedic surgeon may be necessary (Figure 22-4).

Torus Fractures

Torus, or buckle, fractures are common fractures in young children. They result from a compressive load resulting in metaphyseal compaction of trabecular bone and buckling of cortical bone. These fractures are often seen in the distal radius after a fall onto an outstretched hand. As the child matures, the stiffness of the metaphyseal region increases, and the incidence of torus fractures decreases. These fractures are stable and can be managed with simple immobilization for 3 to 4 weeks and orthopedic follow-up (see Figure 22-4).

Bowing Fractures

Bowing fractures represent a plastic deformity of the bone and are unique to children. These fractures occur when a longitudinal force exceeds the bone’s ability to recoil to its normal position and results in a bend in the bone without a fracture. These fractures most commonly involve the radius and ulna. Bowing fractures can sometimes be subtle, and comparison views of the contralateral arm may be necessary. If the deformity occurs in a child younger than 4 years or if the deformation is less than 20 degrees, the angulation usually corrects with growth. However, open reduction may be required for these fractures if they have bowing greater than 20 degrees and the patient is older than 6 years old (see Figure 22-4).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree