Fig. 15.1

ASCCP application for smartphone and tablets

Screening Program Success

The health profession’s success on limiting cervical cancer deaths is based on a confluence of favorable factors. For one, HPV infection causes the vast majority of cervical cancer cases. This has singled out a clear target for prevention and treatment efforts (i.e., HPV testing, immunization) that is lacking in other gynecologic cancers such as ovarian cancer. Secondly, cervical cancer tends to develop gradually through a series of precursor lesions that are identifiable visually and histologically. Lastly, cervical cancer usually invades adjacent structures with loco-regional metastases (i.e., pelvic lymph nodes) before metastasizing to distant organs.

Since the link between HPV infection and cervical cancer was made, much of the focus towards preventing cervical cancer is predicated upon the natural history of HPV. Latency, which refers to the onset of HPV infection to the appearance of cervical cancer, often spans 5–10 years. This provides time for providers to detect HPV infection and HPV-related changes. HPV is not a complete carcinogen as very few of the millions of women infected with HPV every year will develop cervical dysplasia. For women who develop low grade dysplasia or cervical intraepithelial neoplasia 1 (CIN-1), approximately 60 % will spontaneously regress, 10–15 % will progress to a higher grade (CIN-2-3), and only 0.3 % will develop cancer if untreated [12]. Even for women with CIN-3, approximately 30 % will spontaneously regress [13].

Prior to the appearance of cancer, there is a natural progression of precursor lesions CIN-1-3 that are detectable in cervical cytology and visually recognizable by colposcopy. This has enabled colposcopy to evolve from a screening tool into a diagnostic one for the entire lower genital tract including the cervix, vagina, vulva, and anus. Pap smears are not intended to diagnose cervical cancer. In fact, the sensitivity of Pap smears for CIN-2-3 may be as low as 55 % and may miss CIN-3 or cancer up to one-third of the time [14]. Likewise, the main benefit of colposcopy is to identify dysplastic cells amenable to treatment before they progress to cancer.

Colposcopy uses illumination and magnification to direct biopsies and treatment through identification of the TZ and abnormal-appearing lesions. Perhaps its greatest contribution is the ability to identify cells responsible for abnormal cytology without resorting to cervical conization. Unfortunately, colposcopy requires access to expensive equipment, trained practitioners, and access to pathology not available in many underdeveloped countries. In these regions, providers have investigated alternative methods using broad-band light sources (e.g., visual inspection with acetic acid) or see-and-treat algorithms.

Brief History of Procedure

Modern comprehensive cervical cancer screening stems from three separate but intertwined paths—the discovery of cervical cytology, colposcopy, and HPV. In 1927, Aurel Babes, a Romanian physician, presented his findings of cervical cancer smears to the Romanian Society of Gynecology. Concurrently Georgios Papanicolaou, a Greek pathologist working at Cornell Medical College, presented his observations using vaginal pool cytology to detect cervical cancer precursors at the Third Race Betterment Conference in Battle Creek, MI in 1928 [15]. Both presentations were met with harsh criticism, but Papanicolaou persevered and teamed up with a gynecologist Herbert Traut to present his findings in 1941 [16]. In 1949, a visiting Canadian scholar, James Ernst Ayre, worked with Papanicolaou and developed the wooden spatula now used today in various forms to directly sample the cervix.

In 1925, Hans Peter Hinselmann, a German gynecologist, worked in the women’s ward of a hospital in Altona, a district in the northern city Hamburg. He mounted a fixed binocular instrument on a tripod and created an intense light source reflected by a mirror to study the cervix. He used a variety of solutions including cedar wood oil and 5 % silver nitrate. When he applied 3 % acetic acid, he noted tiny, dot-like tumors and leukoplakia [17]. He expanded his findings to include punctation, ground leukoplakia, and mosaic patterns in 1936. He was imprisoned infamously for war crimes related to the forced sterilization of Gypsy women [15]. Walter Schiller, an Austrian pathologist, introduced the use of iodine to aid visualization of abnormal squamous cells that had lost their glycogen content in 1928.

Many US physicians did not accept colposcopy with its cumbersome equipment and variable impressions. In the USA during the early 1960s, enthusiasm gained momentum among gynecologists and pathologists including Walter Lang and Ralph Richart. The ASCCP was formed in 1964. Adolf Stafl, an early pioneer who fled to the USA from Czechoslovakia, joined Johns Hopkins University. He teamed up with a private practitioner, Joseph Scott, and began importing colposcopes and offering instructional courses [18]. By the 1980s, colposcopy became firmly planted as the gold standard to exclude cervical dysplasia and cancer in women with abnormal cytology. It is now an integral part in the management algorithms for the 2012 Updated Consensus Guidelines.

As early as 1842, epidemiological studies revealed that virginal women did not develop cervical cancer [19]. In the 1960s to early 1970s, much interest focused on the viral theory of cancer with host DNA integration and oncogene expression. Herpes simplex virus 2 (HSV-2) was implicated as the sexually transmitted cause but later concluded to be a confounder of increased sexual activity [20]. In 1976, Meisels and Fortin described the appearance of koilocytes in cervical smears of mild dysplasia indicating the presence of HPV [10]. German pathologist Harold zur Hausen isolated HPV-16 as the first cervical cancer-linked HPV subtype [21]. Since then, there have been 14–15 “high-risk” subtypes of HPV associated with cervical dysplasia and cancer.

Data-Supporting Rationale/Efficacy for In-Office Procedure

Indications

There are seven indications for colposcopy by abnormal cervical cytology established in the 2006 and updated 2012 Consensus Guidelines [4, 22]. Colposcopy is not restricted to abnormal cytology alone and may be used for common indications (Table 15.1).

Table 15.1

Indications for colposcopy

Cytology/HPV | Normal (persistent HPV+) |

ASC-US (persistent OR HPV+) | |

ASC-H | |

LSIL | |

HSIL | |

AGC | |

Cancer | |

Visible lesions | Genital warts/condyloma |

Abnormal visual/palpable lesions of cervix, vagina, vulva | |

Ulcers | |

Lichen sclerosus, extra-mammary Paget’s disease | |

Other | In utero DES exposure |

Posttreatment surveillance for CIN-2-3 |

Diethylstilbestrol (DES) was used from about 1940 to 1970 to prevent adverse pregnancy outcomes in women with previous history of miscarriage. In 1971, Herbst published a report linking in utero DES exposure to vaginal clear cell adenocarcinoma, which prompted the FDA to place a black box warning label later that year [23]. Today, women with in utero DES exposure are approximately 40+ years or older.

While there are no absolute contraindications to performing colposcopy, it may be limited in the setting of active pelvic infections (i.e., cervico-vaginitis) such as the classic strawberry spots representing dilated capillary loops in Trichomoniasis or thick vaginal discharge of Candidiasis. Late term pregnancy may yield little treatment information in the absence of gross cervical cancer. Severe vulvo-vaginal atrophy may also yield poor diagnostic information.

Training

The main objective of colposcopy is to prevent cervical cancer by finding cancer precursors using directed biopsies. To accomplish this task, colposcopy requires several essential steps that include applying appropriate indications, maximizing visualization, forming an accurate impression, performing directed biopsies, and establishing appropriate follow-up.

While there is some question to its overall effectiveness and accuracy (see section “Effectiveness”), colposcopy performance is dependent upon provider experience. The continued decline in smoking rates in the USA and introduction of the HPV vaccine is anticipated to erode cervical cancer incidence. Most recently, screening intervals have been extended from traditional annual Pap smears to once every 3–5 years in most women. While this is sure to dwindle the number of colposcopies performed today, it places greater emphasis on establishing the correct diagnosis by colposcopy.

Colposcopy is an office-based procedure, so there are no credentialing requirements by hospitals, insurance companies, or malpractice carriers. The American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology (ACOG) suggests performing 30–50 colposcopies under supervision with an additional 80–100 exams to achieve proficiency [24]. The ASCCP estimates that a provider performs 25–100 colposcopies with a minimum of 10 high grade lesions to become competent. In a 30-question survey sent to 485 Ob/Gyn and Family Practice residency program directors, most programs did not meet the minimum number of procedures for its residents [25]. In a study at a university-based Ob/Gyn residency program, increasing level of training correlated with improvement in accurate impression. Overall accuracy was only 32 %, however, and nurse practitioners outperformed resident physicians [26].

As the number of colposcopy procedures diminishes, it is uncertain whether colposcopy will be practiced widely or become concentrated among providers with keen interest and expertise. For those motivated to perform colposcopy, one might consider obtaining additional teaching at postgraduate curricula offered through various organizations of the ASCCP, ACOG, and American Academy of Family Physicians.

Effectiveness

Colposcopy is considered the reference standard for which cervical cytology is measured. Likewise, histology measures the performance of colposcopy as a diagnostic tool. In 1988, a meta-analysis by Mitchell estimated colposcopy performance at a mean-weighted sensitivity of 96 % and specificity of 48 % comparing all abnormal findings to normal tissue. When comparing only high grade results to low grade abnormalities, sensitivity remained high at 85 % with specificity of 69 % [27].

More recently, it has become recognized that studies often overestimate colposcopy performance due to inherent biases of study design. The methods used to obtain tissue histology are variable (e.g., conization versus colposcopic-directed biopsies) and influence the rate of CIN diagnoses. In many studies, verification bias is introduced when only a select group of women at risk for high grade dysplasia undergo biopsy or treatment. Therefore, calculating the true values for sensitivity and specificity is difficult.

Among experienced colposcopists, there seems to be good interobserver agreement for normal epithelium, high grade dysplasia, and cancer. There is more variability for lesser grade lesions of CIN-1-2 [28]. This was confirmed during the ASC-US and LSIL Triage Study (ALTS) trial, when three experienced reviewers examined digitized images with poor-to-fair agreement on impression [29]. Even for high grade lesions, colposcopy may miss over half of CIN-3 initially [30].

A meta-analysis of 32 studies including 7,873 biopsies examined the diagnostic performance of colposcopic-directed biopsies to that of excisional cervical conization or hysterectomy. Limiting the analysis to four pooled studies with lower rates of positive biopsies provided a more accurate reflection of colposcopic performance to a sensitivity of 81.4 % and specificity of 63.3 % [31]. However, Stoler reviewed the findings of the FUTURE I, II, and III trials in 2011 revealing that LEEP conization diagnosed twice as many CIN-2-3 disease versus same day colposcopic-directed biopsies [32].

It is estimated that over half of missed high grade lesions are due to sampling error [33]. Intuitively, performing more biopsies as opposed to a single biopsy decreases the likelihood of missing a high grade lesion. In the ALTS trial, where only women with ASC-US or LSIL cytologic abnormalities were enrolled, there were 408 women with CIN-3 or cancer of which 69.9 % had a colposcopic-directed biopsy of CIN-2 or greater. Sensitivity increased for procedures with two or greater biopsies [34].

Whether it is better to take multiple biopsies from the most abnormal area, biopsy every abnormal finding, or consider “random” biopsies is uncertain [13]. Belinson and colleagues reported the results of their cross-sectional study Shanxi Province Cervical Cancer Screening Study (SPOCCS I) in 2001 (Table 15.2). Among 1,997 women enrolled, the cervix was divided into four quadrants. “Random” biopsies were performed at the squamo-columnar junction (SCJ) if there was no identifiable lesion, and ECC was performed. Among 86 women with CIN-2 or greater, 16 had normal findings in all four quadrants (12 CIN-2, 4 CIN-3) [35]. In their follow-up study SPOCCS II, they analyzed 364 patients with CIN-2 or greater and a satisfactory colposcopy. The diagnosis of CIN-2 or greater was made by colposcopic-directed biopsy in only 208 (57.1 %). The remaining cases were diagnosed by random biopsy in 136 (37.4 %) and ECC in 20 (5.5 %). The yield for random biopsy was greater at 17.6 % when cytology was high grade versus only 2.8 % when cytology was low grade [36].

Table 15.2

Shanxi province cervical cancer screening study findings

Study | N (#women) | Diagnosis | Diagnosis by biopsy method | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

CIN-2 or worse | Colpo-directed | Random | ECC only | ||

SPOCCS I | 1,997 | 86 | 60 (69.8 %) | 14 (16.3 %) | 2 (2.3 %) |

SPOCCS II | 8,497 | 364 | 208 (57.1 %) | 136 (37.4 %) | 20 (5.5 %) |

SPOCCS I&II | 10,425a | 222b | 141 (63.5 %) | 57 (25.7 %) | 24 (10.8 %) |

The utility of ECC has been debated especially in women with low grade abnormalities. In the ALTS trial, the ECC was positive in only 1 % (10/1,119) of women with a negative colposcopy and biopsy. High grade abnormalities of CIN-2 or greater were found by ECC in 3.7 % of 1,119 exams versus 21.7 % by biopsy. Omitting ECC would risk missing 1.1 % (7/653) of women with CIN-2 or greater. In women <40 years old, only 2 % (7/312) were diagnosed with CIN-2 or greater with low grade biopsy versus 13 % (3/23) women >40 years old [37].

The disparity between colposcopic impression and histology may be attributed to the provider’s experience in forming an accurate impression and/or performing an adequate biopsy. This does not fully explain the poor performance among experienced colposcopists. It is likely that there are some high grade lesions that do not present with classic findings. Jeronimo and colleagues proposed that different subtypes of HPV may present with different aceto-white epithelium (AWE). In the ALTS trial, HPV-16 was associated with AWE regardless of whether the lesion was low or high grade. AWE did not seem to be associated with more HPV types or increased number of lesions, suggesting that other subtypes of HPV were less likely to appear [38].

Among 144 cases of CIN-2-3 in the SPOCCS I study, 111 were diagnosed by colposcopic-directed biopsy with impression of CIN-1 or greater. The average epithelial thickness was 321 μm. Among the remaining 33 cases diagnosed by random biopsy due to normal appearance, the average epithelial thickness was a mere 184 μm [39]. Given that some high grade lesions may not demonstrate typical characteristics, it may be reasonable to perform random biopsies and ECC especially in nonpregnant women with high grade cervical cytology [40].

Diagnostic Effectiveness In-Office and Patient Satisfaction

Colposcopy is considered an office-based procedure. The most common reasons for performing colposcopy in a hospital setting is usually related to poor visualization due to patient anxiety, lack of appropriate equipment, or congenital or acquired anatomic distortion. From both a patient and provider’s perspective, patient comfort is paramount to performing an adequate colposcopy, obtaining biopsies, and ensuring patient follow-up. Many patients express anxiety over the procedure itself, the diagnosis, and potential findings. Strategies to reduce anxiety may include playing music during the procedure, providing pre-procedural videos, and allowing the patient to watch the procedure via video colposcopy [41]. In a survey conducted from 2007 to 2009 of 245 women undergoing colposcopy, patient satisfaction improved if procedural information was provided during a separate pre-procedural visit with a gynecologist or NP as opposed to during the day of the procedure [42].

The cervix has more stretch than pain receptors. There does not appear to be a significant benefit to the use of oral or topical pain relievers. Younger women and women who experience pain with speculum insertion seem to have increased pain perception during ECC [43]. Distraction techniques (e.g., coughing on cue) has been shown to be equivalent to local anesthesia in a small randomized trial [44].

Necessary Equipment

There are multiple types of colposcopes that employ the same basic principles of illumination and magnification (Fig. 15.2). Most colposcopes have adjustments for gross (often movement of entire colposcope) and fine focusing, magnification, intraocular distance, and green/blue light filter. The most common focal length (distance from lens to cervix) is 300 mm (250-mm near, 400-mm far) to enable vision throughout the entire vaginal length. The provider not only needs to sit close to manipulate the speculum and swabs, but also be far enough away to insert biopsy instruments.

Fig. 15.2

Swing-arm colposcope. Other forms for colposcopes include tilt and roller bases or videoscopes. Note motorized height adjustable exam table

The coaxial light source (usually halogen or xenon) is focused at the same distance as the focal length. Magnification ranges from ×2 to ×40 with the most useful range at ×4 to ×15. Many colposcopes will use a numeric value of ×0.4 for scanning and ×2.5 for detail. Note that as magnification increases, brightness diminishes.

Some colposcopes have beam splitters to divert light to either a video camera, still camera, and/or teaching tube. Many patients find it both informative and anxiety-reducing to watch the procedure on a monitor. Patients watching videos during their procedure may be more likely to comply with recommendations [45]. In addition, the ability to take photographs enables more accurate documentation and comparison for patient records.

Positioning is critical for both patient and provider. A height-adjustable stool and motorized exam table are ideal especially for bulkier or less mobile colposcopes. Cervical punch biopsies may be performed with dual cutting jaws (e.g., Tischler, Burke) or anvil-type (Eppendorfer) instruments. One size does not fit all, so having a variety of instruments including straight and angled, long and short is helpful (Table 15.3) (Fig. 15.3).

Table 15.3

Colposcopic instruments and supplies

Instruments | Vaginal speculum (Graves, Pedersen) |

Endocervical speculum | |

Vaginal wall retractor | |

Allis clamp or single-tooth tenaculum | |

Forceps | |

Biopsy (Tischler, baby-Tischler, Kervorkian, Burke, Eppendorfer, Jackson) | |

Endocervical curette | |

Disposables | Cotton-tipped applicator (Fox swabs, Q-tips) |

Gauze | |

Cytobrush | |

Alcohol wipes | |

Sanitary napkin (post-procedure) | |

Solutions | 3–5 % Acetic acid |

Lugol’s solution | |

Fixative | |

Monsel’s solution | |

Silver nitrate | |

Other | Ring forceps |

Needle driver | |

Absorbable suture (e.g., 2-0 Vicryl) | |

Scissors | |

Skin hook | |

Cervical dilators |

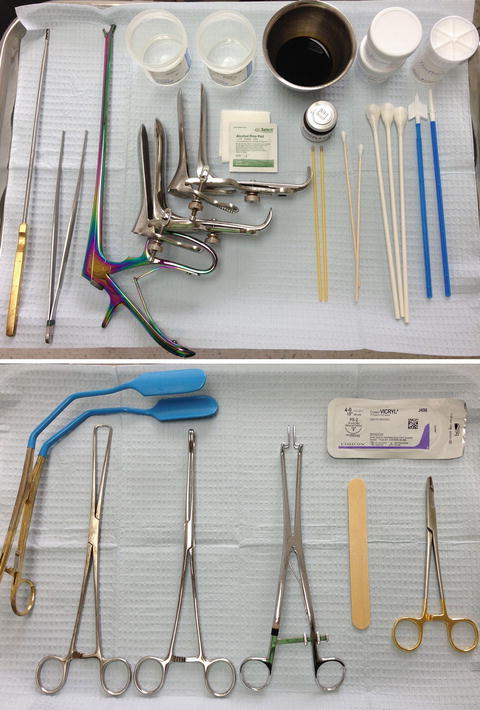

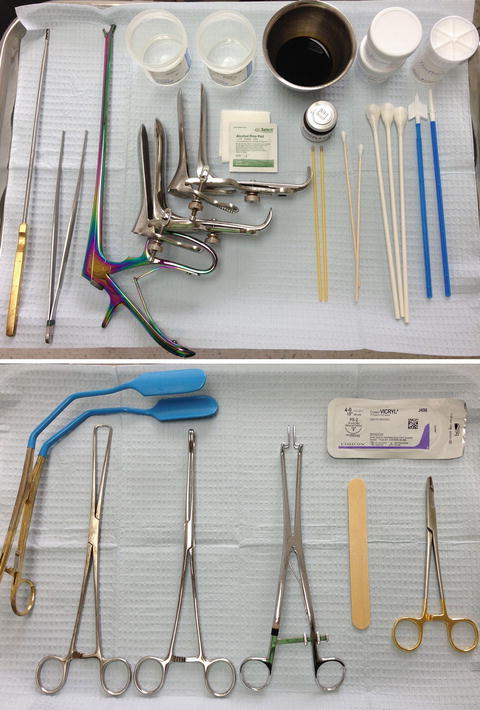

Fig. 15.3

Instrument trays. Main tray is sufficient for most procedures. Accessory tray provides instruments for difficult visualization

Step-By-Step Procedure

Pre-procedure

Prior to the colposcopy procedure, the provider should review the indications for colposcopy to ensure proper guidelines are met. If the Pap smear was performed at another facility, then it is beneficial to request the cytology slides for the pathologist reading the biopsies. Most pathologists will want to corroborate the biopsy results with the cytology. If the patient has any signs or symptoms of cervico-vaginitis, it is beneficial to postpone the visit until this has resolved. Any vaginal creams or douching should be stopped at least 1 day in advance. Relative contraindications to colposcopy include bleeding disorders and anticoagulation therapy so strategies to control bleeding (e.g., discontinuation of anticoagulation) should be implemented prior to the procedure. Colposcopy may be performed in menses if there is light flow.

It is helpful to obtain pertinent patient medical information including last menstrual period, pregnancy and delivery history, and any difficulties with pelvic exams. Prior Pap smear or colposcopy results, previous ablation or conization procedures, and HPV immunization status are important. Modifiable risk factors including previous sexually transmitted diseases, number of sexual partners and practices, and smoking provide opportunity for positive messaging. HIV status, steroid use, uncontrolled diabetes, and organ transplant history provide additional risk factor information. Most importantly, compliance and social situation should be taken into account especially when establishing a follow-up plan.

Check a spot urine pregnancy test in all premenopausal women unless pregnancy status can be confidently assured. The provider should obtain informed consent. The colposcope and any video equipment and monitors should be turned on to avoid fumbling with plugs and cables during the procedure. Clean all eyepieces, handles, and dials between exams.

Procedure

1.

Position the patient and you so both of you are comfortable. This may require the lowest setting on a height-adjustable stool with the motorized bed elevated to avoid slouching. The patient should be low enough on the table in dorsal lithotomy position to ensure visualization of an anterior cervix.

2.

Examine the pelvis in the usual fashion with inspection of vulva, perineum, and anus. You should establish a routine to avoid omitting key parts of the exam. Determine speculum size. The speculum does not need to be excessively large as an uncomfortable patient will limit your exam. A thorough exam can be performed with a smaller speculum but may require more adjustments to visualize the entire area (see below section “Tips and Tricks Section for Trouble-Shooting”).

3.

Obtain a Pap smear (with HPV test if indicated) if the prior cytology was not performed within the past 2–3 months or is unavailable for review. Cervico-vaginal epithelium may take 6 weeks or longer to regenerate after prior smear or biopsy.

4.

Remove mucus, blood, and discharge using a saline swab. Examine for leukoplakia, erosions, ulcers, friable or pigmented lesions, or exophytic growths. Some atypical vessels may appear more prominent before they are obscured by dense AWE. At this point, change gloves to avoid gross contamination of the colposcope or place gloves on handles and dials.

5.

Align the colposcope parallel to the shaft of the vagina. This is where a motorized bed assists in maintaining adequate posture. Start on low magnification ×2 to ×10 to form an overall impression. Avoid focusing on obvious lesions until you have performed a complete survey of the vagina, fornices, and cervix. Increase magnification ×15 to ×20 to inspect vascular patterns. Practice working through the colposcope by passing swabs and instruments without turning away from the colposcopic field.

6.

Apply “vinegar”-soaked swabs to the cervix and vagina. Patients may describe a cold or burning sensation. Anything greater than 5 % acetic acid may burn the mucosa and cause significant discomfort. Allow at least 30–60 s for the solution to absorb. It is postulated that acetic acid causes swelling in both columnar and abnormal cells. Other theories include reversible coagulation or precipitation of nuclear proteins and cytokeratins. The “light reflex” refers to the white appearance when light is reflected by large, dense nuclei of dysplastic cells rather than transmitted through the 20–30 cell epithelial layer (see section “Findings”).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree