15 Cognitive-Perceptual Disorders

Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder, Learning Problems, Sensory Processing Disorder, Autism Spectrum Disorder, Blindness, and Deafness

Gordon (2010) describes the cognitive-perceptual functional health pattern to include the adequacy of sensory modes, such as vision, hearing, taste, touch, or smell, as well as the cognitive functional abilities such as language, memory, and decision-making. Sensory experiences such as pain (see Chapter 22) and altered sensory input may also be identified.

Piaget’s theory of cognitive development is probably the most classic (see Chapter 4). Newer theories and ideas related to the development of cognition and sensory awareness are emerging and being developed. Neurodevelopmental functioning of the brain uses a model of a tool kit full of basic instruments (functions) with different functions working in clusters (like tools) in different kinds of learning. The concept of multiple intelligences was introduced to describe different ways a child may be hard-wired to process information. Information processing looks at human learning with a computer as a model. Social cognition looks at the spectrum of social behaviors and affiliation with others.

Facilitating and monitoring cognitive-perceptual developmental progress as well as ensuring the maximum function of all the senses should be an integral part of primary care. Screening hearing and vision is a recognized standard of care. Following cognitive development in infancy and early childhood is primarily done by monitoring language and problem-solving domains integral to the other developmental parameters and should ideally be performed with standardized screening tools. As the child enters school, monitoring the adaptation to and performance in school becomes the key. Soliciting information about school performance from preschool through high school shows interest in the child’s mastery of educational tasks and managing academic challenges. Primary care providers may be consulted for guidance about appropriate timing and school placement for a child, performance more or less than expectations, problems, and the need for further assessment. As developmental experts, primary care providers need to be able to identify problems; advise, counsel, and educate parents; participate on interdisciplinary teams for diagnosis and management; and mediate and advocate for children and their learning needs.

Theories of Normal Cognitive-Perceptual Development

Theories of Normal Cognitive-Perceptual Development

Piaget: Cognitive Development

Piaget’s learning model is discussed in detail in Chapter 4, but key concepts include assimilation (taking in information through any and all the senses), accommodation (taking one’s current abilities/understanding and modifying them to adjust to the new circumstance or challenge), schema (organizing this into a new mental structure or physical action), and equilibrium (a new level of cognition).

Neurodevelopmental Framework

There are eight constructs to the neurodevelopmental framework, which are listed in Table 15-1. Identifying a child’s strengths and weaknesses by using these constructs provides a method to describe, organize, and address individual students’ learning needs.

TABLE 15-1 Constructs of the Neurodevelopmental Framework

CNS, Central nervous system; REM, rapid eye movement.

Multiple Intelligences

In 1983 Dr. Howard Gardner, a professor of education at Harvard University, developed the theory of multiple intelligences to account for the broad range of human potential in children and adults. Gardner believed the traditional measure of intelligence, based on IQ testing, was inadequate and left many talented and intelligent children and adults floundering (Smith, 2010). He identified eight different intelligences (Table 15-2) that many educational systems have begun to use.

TABLE 15-2 Multiple Intelligences

| Intelligence | Description |

|---|---|

| Linguistic | Sensitivity to language; language-based function (word smart) |

| Logical-mathematical | Abstract reasoning, manipulation of symbols, detection of patterns, logical reasoning (number/reasoning smart) |

| Musical | Detection and production of musical structures and patterns; appreciation of pitch, rhythm, musical expressiveness (music smart) |

| Spatial | Visual memory, visual-spatial skills, visualization (picture smart) |

| Body-kinesthetic | Representation of ideas, feeling in movement; use of body, coordination, goal-directed activities (body smart) |

| Naturalistic | Classification and recognition of animals, plants (nature smart) |

| Social/interpersonal | Sensitivity and responsiveness to moods, motives, intentions and feelings of others (people smart) |

| Personal/intrapersonal | Sensitivity to self, feelings, strengths, desires, weaknesses and understanding of intention and motivation of others (self smart) |

Information-Processing Theories

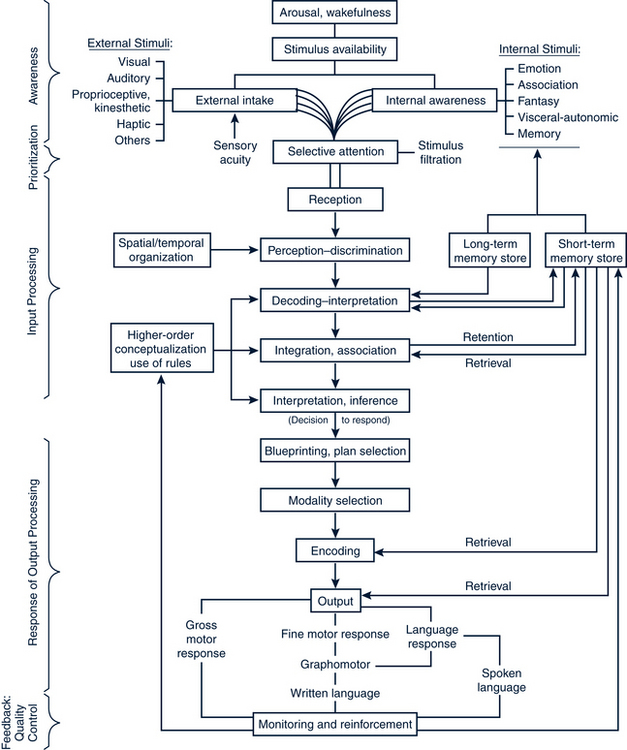

Process components include rehearsal activity—used to keep information in the short-term store, the working memory; automatic processing—transforms information outside the direct control of the individual to retain information not consciously remembered; and the task environment or the context of the child—for example, a particular solution to a problem may create moral conflicts and thus alter the child’s options. Figure 15-1 illustrates an information-processing model.

Social Cognition

• Understand thoughts, intentions, and emotions of self and others

• Follow the rules of social play, to regulate one’s own responses to unstructured or ambiguous social environments

• Understand/anticipate how peers feel (empathy)

• Communicate and comprehend social meaning; understand body language and perceive faces

• Infancy—eye contact, social smile, reaching, emerging joint attention, use of others’ emotions to regulate self

• Toddler/preschool—emerging empathy, understanding social rules, constructing narratives and reciprocity in play

• School age—functioning successfully and flexibly in both structured and unstructured situations; “street smart”

• Adolescence—forming social group affiliations and emerging sexual identity; social testing and teasing

The Societal-Familial-Individual Matrix of School Achievement

Wegner (2009) proposes a matrix of societal, family, and individual elements that affect a child’s ability to achieve academically. Success can be defined as “successful attainment of skills commensurate with the child’s cognitive profile” and is often measured by passing all grades in school. This matrix offers a way to examine the interplay of a child’s individual profile, family factors, and community characteristics.

Cognitive-Perceptual Development Problems and Primary Care

Cognitive-Perceptual Development Problems and Primary Care

Assessment

History

• Genetic elements—any disorder, condition, or malformation with identifiable cognitive effect (e.g., trisomy 21, velocardiofacial syndromes)

• Prenatal factors—risk factors such as maternal/paternal age at conception; maternal use of tobacco or alcohol; maternal hypertension and other complications; fetal hypoxemia or suboptimal growth

• Birth and perinatal events—adverse events during delivery; prematurity; prolonged neonatal complications

• Infancy to 3 years—maternal depression; family wellness indicators; parental literacy, child deprivation, neglect, or abuse

• Three years through kindergarten entry—child interaction difficulties in larger group settings; lack of independent play or sustained interest in preferred activity, lack of expanding conversation and interactions with adult

• School age and adolescence—difficulties in academic settings, problems with interactions with peers or in large group settings

Screening

A developmental screening tool should be used consistently throughout the first 6 years of life to monitor children for any delay or lagging performance. Developmental screening is discussed in detail in Chapters 4 through 8. Cognitive red flags are listed in Box 15-1. Screening for autism using the M-CHAT is recommended at 18 and 24 months (see later section on Autism). Concerns about a child’s ability to deal with sensory input from either a learning or behavioral standpoint can be evaluated with a screening tool (see later section on Sensory Processing Disorder).

BOX 15-1 Cognitive Red Flags

• 4 months—lack of visual tracking

• 6 months—failure to turn to sound or voice

• 9 months—lack of babbling consonant sounds

• 24 months—failure to use single words

Data from Wilks T, Gerber R, Erdie-Lalena C: Developmental milestones: cognitive development, Pediatr Rev 31(9):364-367, 2010; American Academy of Neurology and the Child Neurology Society: Guideline summary for clinicians: screening and diagnosis of autism, 2010. Available at http://aan.com/professionals/practice/guidelines/guideline_summaries/Autism_Guideline_for_Clinicians.pdf (accessed Jan 5, 2011).

• Early elementary (grades 1 through 3) lays the foundation for the remainder of a child’s schooling. Differentiating early struggles due to temperament, environment or cognitive-perceptual weaknesses may be difficult.

• Later elementary (grades 4 through 6) is characterized by increasing demands and needed independence. Complaints of being bored (gifted versus overwhelmed child); and difficulty with emerging complex social hierarchy and peer influences are important to detect.

• During middle school, demands on the child’s independent direction increase, parental and teacher direction decreases, and physical and cognitive changes occur. This may cause some children to struggle academically, have poor outcomes related to peer influence, and have worsening of any chronic health condition.

• High school results in greater grade pressure as students compete for university and vocational school placements and scholarships. Adolescents have a need for autonomy and individuation as well as identification of personal strengths and goals.

Management Strategies

Educational Strategies

Children with cognitive-perceptual problems are entitled to special education opportunities to maximize their learning potential. Infant stimulation opportunities are extremely important and early-intervention preschool programs are essential (see Chapter 4).

Two federal laws, the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), passed in 1990, and the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), reauthorized in 1997, provide mandates for reasonable accommodations that schools must provide to help children with disabilities to achieve meaningful, equal opportunity to benefit from educational services. Free and appropriate public education (FAPE) and least restrictive environment (LRE) are ideas that are built into the special education system. A response to intervention (RTI) approach is a tiered response to determining if a child has a disability and qualifies for special education. It is more effective in identifying students with learning disabilities than the traditional IQ discrepancy model. Once a child has been identified with special learning needs, an Individualized Education Plan (IEP) or a 504 plan are two means of delineating help for the child. Table 15-3 provides a differentiation of services.

• The IEP originates from the IDEA and is designed for children who demonstrate a gap between learning potential and actual academic performance. An IEP is a written plan defining the child’s disabilities, current level of educational performance, educational needs, and specific annual goals developed by a multidisciplinary team with parent involvement. An IEP includes specific academic, communication, motor, learning, functional, and socialization goals.

• The Section 504 plan specifies “reasonable accommodations” to help children with disabilities benefit from their education. Eligibility is based on the existence of an identified physical or mental condition that “substantially limits a major life activity” (learning). Each school district handles 504 plans differently, but there should be a 504 coordinator that oversees the process. Many children with ADHD and learning disabilities who do not have cognitive deficits but do have learning weaknesses, or behavioral or emotional problems that interfere with learning are eligible for a 504 plan.

TABLE 15-3 504 and Individualized Educational Plan (IEP) Evaluation and Educational Plans

ADHD, Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; IDEA, Individuals with Disabilities Education Act; IEP, Individualized Educational Plan.

Cognitive-Perceptual Problems of Children

Cognitive-Perceptual Problems of Children

Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder

Description

The core symptoms of ADHD are inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity. In ADHD these symptoms occur at a developmentally inappropriate level. There is a range of severity of symptoms from one individual to the next. Also, the scope and severity of behaviors may change within an individual as maturation occurs. The criteria defining ADHD were established by the American Psychiatric Association (APA) in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition (DSM-IV) (APA, 2000) (Table 15-4).

TABLE 15-4 DSM-IV-TR Criteria for Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder

| Domain | Criteria |

|---|---|

| Essential features | • Some symptoms that caused impairment were present before age 7 years • Some impairment from the symptoms is present in two or more settings (e.g., at school [or work] and at home) • There must be clear evidence of significant impairment in social, academic, or occupational function • The symptoms do not occur exclusively during the course of a pervasive developmental disorder, schizophrenia, or other psychotic disorder and are not better accounted for by another mental disorder (e.g., mood disorder, anxiety disorder, dissociative disorder, or personality disorder) |

| Six or more of the following symptoms of inattention: | |

| Hyperactivity/Impulsivity traits | Six or more of the following symptoms of hyperactivity-impulsivity: |

From American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fourth edition, text revision, Arlington, VA, 2000, American Psychiatric Association.

ADHD has three different diagnostic subtypes depending on the number of positive symptoms in each category (Box 15-2).

BOX 15-2 Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) Diagnostic Subtypes

Data from Lollar DJ: Function, impairment, and long-term outcomes in children with ADHD and how to measure them, Pediatr Ann 37(1):28-36, 2008.

Etiology

Prevalence in the U.S

ADHD prevalence rates vary depending on the source, criteria used to make the diagnosis, and the ages sampled. Overall, the rate of ADHD diagnosis is increasing at a higher rate among teenagers than among younger children (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2010b; Pastor and Reuben, 2008). There is a 9.5% prevalence for children between 4 and 17 years (5.4 million children), based on parental report of their child having been diagnosed with ADHD (CDC, 2010a). Rates by age are cited as 4- to 10-year-olds, 6.6%; 11- to 14-year-olds, 11.2%; and 15- to 17-year-olds, 13.6%. In 2007, 4.8% of children diagnosed with ADHD were being treated with medication for this condition. ADHD has always been more prevalent in boys than in girls. Current rates show the prevalence in boys at 13.2% and in girls at 5.6% (CDC, 2010a). Girls are more likely than boys to have the symptoms of ADHD, predominantly inattention. This subtype also has greater academic difficulty than ADHD, predominantly hyperactive/impulsive. About 4% of children with ADHD also have a diagnosed learning disability (Pastor and Reuben, 2008).

Effect on Individuals, Families, and Communities

Because ADHD symptoms cross over so many settings and are chronic, often into adulthood, this condition has a major effect on the individual as well as on his or her family and community. Table 15-5 summarizes impairments across the life span. In families in which ADHD is present, significantly higher levels of stress (than in the general population) are reported. Individuals with ADHD (with and without comorbid conditions) have six times greater difficulty in the areas of friendship with peers, and emotional, and conduct problems than their nonaffected peers. There is a nine times greater likelihood of family stress; problems with classroom learning and conduct; and difficulties with leisure activities (e.g., playing with friends or participating on a sports team) (Strine et al, 2006).

TABLE 15-5 Summary of ADHD Impairments Across the Life Span

| Life Stage | Impairment |

|---|---|

| Childhood | |

| Adolescence | |

| Adulthood |

ADHD, Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder.

Adapted from Pliszka S, American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (AACAP) Work Group on Quality Issues: Practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 46(7):894-921, 2007; Spencer TJ, Biederrman J, Mick E: Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: diagnosis, lifespan, comorbidities and neurobiology, Ambul Pediatr 7(3):73-81, 2007.

ADHD is also a significant cause of family stress and financial burden. Parents of children with ADHD report days of missed work due to the child’s school and medical appointments. Many of the services required for adequate evaluation and treatment of ADHD are not covered by health insurance (e.g., psychological testing, mental health care, or educational testing beyond that done at the school). The average annual direct health care costs for an individual with ADHD are $1,574 compared with $541 for a matched control without ADHD (CDC, 2010a).

Pathophysiology

Environmental Factors

• Prenatal maternal tobacco use. Prenatal maternal tobacco use is associated with a 2.4-fold increased risk of ADHD (Froehlich et al, 2009).

• Prenatal alcohol use. Direct association with ADHD is not as well established in the literature (DynaMed Database, 2010).

• Lead exposure. Froehlich and associates (2009) report a direct correlation between early lead exposure and later ADHD diagnosis even with low lead levels (<10 mcg/dL).

• Prematurity and low birthweight. Prematurity and low birthweight increase ADHD risk by 2.64-fold (DynaMed Database, 2010).

• Food additives (artificial colors and flavors). There have been a number of studies in this area and none have shown a causal connection between food additives and ADHD. Elimination of food additives is not a recommended part of any ADHD practice guidelines (Krull, 2010b).

• Refined sugar. Although some children respond to excessive sugar with an increased activity level, reviews of many studies fail to show an association with sugar and ADHD (Krull, 2010b).

• Essential fatty acids (omega 3 and omega 6). These nutrients are integral in the development and functioning of neuronal membranes. Three studies showed no benefit to fatty acid supplementation for children with ADHD, although benefits were found in one study (Krull, 2010b).

• Iron deficiency. Low serum ferritin is associated with learning difficulties. One study showed that children with ADHD had lower serum ferritin levels than matched non-ADHD children. Another study (Krull, 2010b) showed that iron supplementation in children with low serum ferritin levels improved ADHD symptoms.

• Zinc. Limited research has demonstrated zinc deficiency in children with ADHD and/or a benefit from zinc supplementation on ADHD symptoms (Krull, 2010b).

Clinical Findings

Often the patient presents to the provider after having been referred by a child care provider, the school, or the parent/guardian for concerns about excessive energy and activity, fidgety behavior, distractibility, poor school performance, poor relations with peers, aggressive behavior, failure to organize or complete tasks, or some variation of these symptoms. ADHD symptoms can affect the very domains of life where children and adolescents are working on developmental mastery—school, peers, family life, sports, and recreational activities. If the presenting complaint/visit is not specifically about school or behavioral concerns, it is important for the provider to inquire about those areas of the patient’s life.

Assessment

The diagnosis and management of ADHD can be made in the primary care pediatric office, but involves working with the child’s school and other domains where the child regularly spends time (e.g., after-school or childcare programs, sports activities, etc.). There is no “one” assessment tool to diagnose ADHD though there are a number of tools and evidence-based practice guidelines that are available to help clinicians develop an organized, efficient, and safe practice in assessing, diagnosing, and caring for children and adolescents with ADHD. Table 15-6 provides resource information for the four main guidelines.

TABLE 15-6 Clinical Tools and Evidence-Based Guidelines for ADHD Assessment and Treatment

| Name of Tool or Guideline | Age Applicable | What Is Included |

|---|---|---|

| National Initiative for Children’s Healthcare Quality (NICHQ) and American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP): Caring for children with ADHD: a resource toolkit for clinicians (www.nichq.org/resources/ADHD_toolkit.html) | School-age children and adolescents | Materials for ADHD diagnosis and management based on the DSM-IV criteria for school-age children and adolescents; Vanderbilt ADHD assessment tool and scoring information |

| Ages 6 to 12 years | Algorithm and practice recommendations for assessment, diagnosis, and treatment | |

| Ages 3 through 17 years | Recommendations about assessment, diagnosis and treatment | |

| Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement (ICSI) Health care guideline: Diagnosis and management of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in primary care for school-age children and adolescents, March 2010 (www.icsi.org) | School-age children and adolescents | Algorithms for diagnosis and treatment, background on ADHD, tables about ADHD medications, table of the full DSM-IV-TR diagnostic criteria |

ADHD, Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; DSM-IV, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition.

The components of the ADHD assessment include:

• Interview of parent and child or adolescent for history gathering

• Gathering information about symptoms on standardized ADHD behavioral assessment scales from several different sources (parents, caregivers, teachers, sports coaches)

• Gathering other pertinent evaluations (if done) such as school testing and psychological or other mental health evaluations

History

Table 15-7 outlines many of the areas for assessment and suggested topics to explore in taking a history when evaluating for ADHD.

TABLE 15-7 Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder History

| Assessment Area | Suggested Topics to Explore |

|---|---|

| Chief complaint and history of present problem | Major areas of concern |

| First awareness of problem | |

| Beliefs about causation of problem | |

| Previous evaluations and results | |

| Medication history for behavioral, emotional, or learning problems | |

| Birth history* | Prenatal history; maternal health; use of medications, recreational drugs, alcohol, and tobacco during pregnancy |

| Prematurity, low birthweight or IUGR | |

| Birth and postpartum complications, anoxia, difficult delivery, birth defects | |

| Neonatal behavior: feeding, sleep, temperament problems | |

| Medical history | Chronic diseases, ongoing medications |

| Hospitalizations, prolonged illness | |

| Trauma history (head injury, frequent injuries) | |

| Poisoning or lead or environmental exposures | |

| Neurologic status, seizures, tics, habit spasms, uncontrolled twitches, outbursts of uncontrollable sounds or words | |

| Environmental allergies | |

| Cardiovascular history (see section about cardiovascular risks with stimulants) | |

| General health* | Vision, hearing |

| ADHD history | Attention: paying attention, sustaining attention, listening, following through, organization, reluctant to engage in activities that need sustained attention, loses things, distracted, forgetful |

| Activity: fidgets, leaves seat, runs or climbs when inappropriate, has difficulty with quiet games, talks excessively, has problems waiting turn, interrupts, “on the go” | |

| Developmental history* | Milestones: motor, personal-social, language, cognitive |

| Strengths (e.g., personality, activities, friendliness) | |

| Weaknesses | |

| Behavioral history* | Frequency with which child complies when told to do something |

| Methods used at home to improve behavior and effectiveness | |

| Parenting skills and style, cultural beliefs | |

| Parental agreement about child management | |

| Counseling history for child or family (or both) | |

| Academic history | Child’s progress at each grade level (strengths seen) |

| Adjustment problems at school, child’s history with peers, friendships | |

| Difficulties with specific skills: reading, writing, spelling, math, concepts | |

| Performance problems: attention, grades, participation, excessive talking, disturbing others, fighting, bullying, teasing, abusive language, not completing work | |

| School assistance: tutoring, counseling, special help | |

| Functional Health Patterns | |

| Feeding | Not able to sit through a complete meal |

| Messy and clumsy with utensils, dishes, and glasses | |

| Inadequate caloric intake can be result of symptoms and further exacerbated by medications used to treat ADHD | |

| Gastric distress may be a side effect of stimulant medication | |

| Elimination | Enuresis, encopresis |

| Sleeping | Difficulty falling asleep, night waking, needs less sleep than other family members |

| Complains about fatigue interfering with completion of tasks | |

| Activity | Difficulty maintaining routines for activities of daily living |

| Cognitive | Level of performance is below potential for achievement |

| Tends to miss the point of conversations and activities | |

| Often does things the hard way in absence of established routines | |

| Self-concept | Struggles with low self-esteem, moodiness |

| Role relationships | Births, deaths, deployment |

| Marriage and family transitions: separation, divorce, remarriage | |

| Violence: domestic, current or past abuse of parent or child; problems with the law; weapons in the home | |

| Inadequate social and relational skills | |

| Lies, steals, plays with fire, hurts animals, is aggressive with other children, talks back to adults | |

| Coping and stress tolerance | Family stress and coping patterns |

| Stressors: parent job loss or change, financial problems | |

| Outbursts of temper, low tolerance for frustration | |

| Moody, worried, sad, quiet, destructive, fearful or fearless, self-deprecating | |

| Somatic complaints | |

| Social and environmental history* | General family relationships (child and parents/siblings) |

| Home, daycare, and school environments | |

| Family social risk factors: recent moves, financial stress, parental job losses, births, deaths, divorces, remarriages, alcohol and drug use, involvement with law enforcement, weapons in the home | |

| Family history* | ADHD, neurologic problems, learning difficulties |

| Mental health history of close family members, health or behavior problems in other family members | |

| Genetic disorders: cognitive disabilities, growth disorders, neurofibromatosis | |

| Drug or alcohol abuse (current and/or past) | |

| Teacher history | Obtain information from school about child’s problems, strengths, weaknesses, academic management of issues |

ADHD, Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; IUGR, intrauterine growth retardation.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree