CHAPTER 11 Cognitive and Adaptive Disabilities

PURPOSE

The direct and indirect economic costs associated with mental retardation in the United States are significant: $51.2 billion (2003 dollars) for persons born in 2000.1 The proportion of school-aged children classified as having “mental retardation” and receiving services in federally funded educational programs in the United States has stabilized since the early 1990s between 1.26% and 1.28%.2 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention currently estimate that mental retardation is diagnosed in 12 per 1000 U.S. school-aged children; the result in annual special education costs is $3.3 billion.

TERMINOLOGY DEBATE

The terminology used to describe mental retardation has changed since the 19th century, reflecting an increased sensitivity to the rights of and opportunities for persons with mental retardation, an increased effort to mainstream individuals with mental retardation into society to improve their quality of life, and a decreased tolerance for stigmatizing and limiting “labels” that focus on the disability rather than on the individual. The terms imbecility and idiocy were used in the late 19th century to describe different levels of intellectual functioning on the basis of decreasing language and speech abilities. Less affected individuals were referred to as being “feeble-minded.” At that time, the outcome for individuals with mental retardation was believed to be predetermined; their ability to participate in everyday activities and within typical environments was limited. In the mid-20th century, terms such as trainable and educable were used to characterize persons with mental retardation, often to suggest what type of educational experience was most appropriate. Newer educational interventions that emphasize mainstreaming have reversed this focus on limiting participation and minimizing progress. What has remained, however, is the need to distinguish between a label, the specific difficulties faced by an individual with that label, and the social judgments associated with that label.3 Effective differentiation between the label and the individual and advocacy for the integration of these children and their families into every aspect of society is an essential responsibility of developmental-behavioral pediatricians and every other member of the multidisciplinary teams providing their care.

There are numerous negative connotations associated with the term mental retardation. There is no agreement on a more preferred term at either the international or national level. Other terms that have been proposed include intellectual disability/disabilities, developmental disabilities, mentally challenged, and cognitive adaptive disability or delay. In the United Kingdom, the term learning disability is used, whereas intellectual disability is preferred in Japan and is increasingly the label of choice among the international community.4

As it prepared to revise its 1992 definition for mental retardation, the American Association on Mental Retardation (AAMR) asked for comments and recommendations for an alternative term that would better describe these individuals. One strongly considered proposal was cognitive adaptive disability. Interestingly, this evolving discussion of a “best” or “better” term eventually led to a change in the name of the President’s Committee on Mental Retardation to the President’s Committee on Intellectual Disability. There are very strong arguments that any other term selected to describe this group of individuals will quickly assume similar negative connotations. It is also important to realize that what is “acceptable” to professionals may not be so readily accepted by affected individuals and their families. There have also been concerns that changing the term used to describe these individuals might adversely affect their eligibility for services specifically defined in statute for “persons with mental retardation” (supplemental Social Security payments) and for unique legal protections provided by this diagnosis (death penalty exclusions). The debate over the correct terminology for this condition continues. In January 2007, the American Association on Mental Retardation (AAMR) officially changed the organization’s name to the American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities (AAIDD). Although they recognize that the condition “mental retardation” they have defined for over 100 years still exists, the AAMR/AAIDD leadership feels that this change is “an idea whose time has come.”

DEFINITION AND CRITERIA

A state of mental defect from birth, or from an early age, due to incomplete cerebral development, in consequence of which the person affected is unable to perform his duties as a member of society in the position of life to which he is born.5

There are two generally well-accepted organizational definitions of mental retardation: the AAMR’s and the American Psychiatric Association’s as described in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition, text revision (DSM-IV-TR) (Table 11-1).5,6 The two schemes have common elements: the use of standardized measures of intelligence and adaptive abilities to define levels of significant subaverage intellectual and adaptive functioning and evidence of the disability’s presence before 18 years of age. In current definitions, mental retardation is no longer described as a state of “global incompetence.” Instead, they refer to an overall pattern of limitations and describe how individuals typically, not ideally, function in various contexts of their everyday life.

TABLE 11-1 Current Definitions of Mental Retardation

| Feature | AAMR, 2002 | DSM-IV-TR |

|---|---|---|

| Intellectual functioning | Significant limitations in intellectual functioning | |

| Adaptive functioning | Significant limitations in adaptive behaviors as expressed in conceptual, social, and practical adaptive skills | Concurrent impairments in two of the following areas: communication, self-care, home living, social skills, community skills, self-direction, functional academic skills, work, leisure, health, and safety |

| Age at onset | Before 18 years | Before 18 years |

AAMR, American Association on Mental Retardation5; DSM-IV-TR, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed, text revision (American Psychiatric Association6).

In discussions with families, it is very important to remember that cognition, intelligence, and IQ are not synonymous terms; confusion and disagreement often occur when they are used interchangeably. Intelligence is a combination of the ability to learn and to pose and solve problems.7 Various schemas for intelligence have been proposed with complementary and overlapping features.

Levels of Mental Retardation

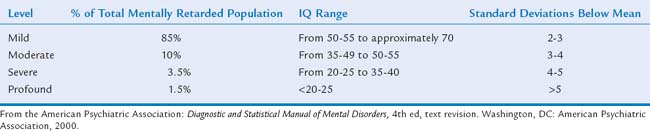

In the traditional classification schema, continued in the DSM-IV-TR system, the number of standard deviations below the mean is its basis (Table 11-2). There are both advantages and disadvantages to this schema. It is often preferable for research purposes because of its ability to better define a “homogeneous” population. However, the fact that a numerical “score” from a standardized measure of intelligence may vary by as much as 5 points higher or lower (95% confidence interval) still limits the effectiveness of a specific score as a method of differentiation across severity levels. In other schemas, particularly for epidemiological analyses, an IQ cutoff score of 50 is used to differentiate between “mild” and “severe” mental retardation.8 The reason for this division was to define and describe individuals who would benefit from a formal/academic education program (mild) from those who would benefit more from a life skills education program (severe). Likewise, the same differentiation could be applied to individuals who would be able to live independently (mild) from those more likely to need a guardian and additional supervision (severe).

Levels of Support

The 1992 edition of AAMR’s definition of mental retardation introduced a significant change in the organizational and descriptive approach to individuals with mental retardation: the concept of “levels of support.” AAMR further developed this concept and proposed the current definition in 2002: “Supports are resources and strategies that aim to promote the development, education, interests and personal well being of a person and that enhance individual functioning.”5

The supports approach purpose is to evaluate the specific needs of the individual and then suggest strategies, services, and supports that will optimize individual functioning across the various dimensions of intellectual functioning. These resources and strategies can be the result of a person’s own efforts or help from other individuals (natural sources), or it can be the result of additional technology, agencies, or service providers (service-based sources). The goal of these interventions is to improve personal functioning, promote self-determination and societal inclusion, and improve the personal well-being and functional abilities and outcomes of a person with mental retardation. In many ways, this method parallels the evolving attention to not only the cognitive and adaptive limitations but also the specific abilities of an individual.5 In an effort to provide a comprehensive assessment, an evaluation is recommended in at least nine key areas: human development, teaching and education, home living, community living, employment, health and safety, behavior, social function, and protection and advocacy. Within these areas, such supports as teaching, befriending, financial planning, employee assistance, behavioral support, in-home living assistance, community access and use, and health assistance may be required. The level of support method recognizes that an individual’s needs and circumstances change over time and are influenced by an individual’s environment. Supports are dynamic.

As a support schema is developed, two additional characteristics must be considered: support dimensions and support intensity. Five dimensions of intellectual ability in which an individual may require additional support have been identified (Table 11-3). Each individual has different needs and therefore requires different supports in each of these dimensions. The intensity, frequency, and acuity of what an individual requires in support are also not uniform across these various dimensions (Table 11-4).

TABLE 11-3 Dimensions of Mental Retardation

| Intellectual abilities | Communication, functional academics, vocational skills |

| Adaptive behavior | Self-care, home living, integrated vocational opportunities |

| Social roles, participation, interactions* | Community living, friendships, self-esteem, social skills, leisure activities |

| Health concerns (physical, mental, etiological) | Etiology and conditions related to biological processes; comorbid disorders |

| Context considerations | Environments, cultures |

From American Association on Mental Retardation. In Luckasson RA, Schalock RL, Spitalnik DM, et al, eds: Mental Retardation: Definition, Classification, and Systems of Support, 10th ed. Washington, DC: American Association on Mental Retardation, 2002, pp 99-121.

TABLE 11-4 Support Intensity Levels

| Intermittent | |

| Limited | |

| Extensive | |

| Pervasive |

*New dimension as of 2002.

From American Association on Mental Retardation. In Luckasson RA, Schalock RL, Spitalnik DM, et al, eds: Mental Retardation: Definition, Classification, and Systems of Support, 10th ed. Washington, DC: American Association on Mental Retardation, 2002, pp 145-168.

The most recent evolution in this method is the AAIDD’s development of the Supports Intensity Scales.9 This instrument provides a direct assessment of the support needed on an individual basis that is not inferred from a “score” derived from other instruments whose norms are based on the general population and not specifically on individuals with disabilities.10

Prevalence

The statistical prevalence of mental retardation is approximately 2% to 3%, although the actual prevalence may be closer to 1%. The estimate varies according to the particular study, specific ascertainment methods, the age of the cohort being studied (lower prevalence among subjects aged <5 years and >18 years—i.e., non-school-aged cohorts), and the level of impairment. Multiple studies and surveys have demonstrated that specific populations are overrepresented; the label “mental retardation” is more likely to be applied to individuals of lower socioeconomic status, ethnic groups, and cultural minority groups; those in institutions; and those with related conditions (cerebral palsy, spina bifida, autism).11–13 The prevalence of severe mental retardation (IQ < 50) has remained stable at approximately 0.4% to 0.5%; it is much more likely to be associated with organic disorders and causes. Because of the more variable upper diagnostic limits, the prevalence of mild mental retardation (IQ of 50 to ≤70-75) is more difficult to ascertain. Nevertheless, the vast majority (approximately 85%) of persons with mental retardation have IQ scores in the “mild” range.

ETIOLOGY

Risk Factors in Mental Retardation

Studies of intelligence with standardized IQ measures have produced evidence for a significant genetic influence, although experience and environment also influence this innate ability: 50% of the IQ test score variation can be attributed to genetic variation.14 Heritability estimates for general intelligence appear to be approximately 0.45 to 0.75; longitudinal studies have shown this factor to increase steadily from infancy through adulthood.15 Different genes may play a role, each with a varying degree of effect (quantitative trait loci).15 Children with birth defects are 27 times more likely to have mental retardation by 7 years of age than are children without a diagnosed birth defect, regardless of the type of defect.16

Different risk factors for mild and severe levels of mental retardation are known. Sameroff and associates17 found that the presence of multiple risk factors at age 4 were an important predictor of children’s IQ at age 13. The cumulative effect of multiple risk factors can have an adverse effect on academic success from 1st through 12th grade, overcoming any bolstering effect of intelligence and positive mental health.18 Low maternal education level continues to be the strongest predictor of mild mental retardation. Women with less than 12 years of schooling are more likely to have a child with a mental retardation placement in school than are mothers with some degree of postsecondary education.19 Women with only high-school diplomas still have an increased, albeit lower, risk. Numerous studies have demonstrated an increased risk for isolated severe mental retardation in boys and men (1.4:1) and in nonwhite populations (2:1).20 Therefore, both nature and nurture play important roles in cognitive development. Genetics appears to provide the cognitive potential that is then shaped and developed by environmental and self-selected experiences that further modify a person’s behavior.

Etiological Diagnosis of Mental Retardation

Efforts to identify specific causes of mental retardation are driven by the hope that defining a cause will improve the ability to prevent mental retardation from that cause. However, an etiological diagnosis is made in less than one half of individuals with mental retardation.21 A major challenge in defining an etiology for mental retardation remains in characterizing the contribution and interaction of various socioeconomic factors and other factors in association with prenatal, perinatal, and postnatal events. The number of cases attributed to specific diagnostic categories varies according to the degree of mental retardation, patient selection criteria (including age of the patient), study protocols, technological advances over time, and definitions of diagnoses.22 Because of these issues, classification systems based only on timing or etiology, although more frequently used, may be incomplete. Moog23 proposed a “dynamic classification system” that distinguishes among genetic, unknown, and acquired causes with additional consideration to the degree of diagnostic certainty.

“Diagnostic uncertainty” has a significant effect on families and their ability to cope with the stresses associated with a child having mental retardation. In one comparison of levels of anxiety, feelings of guilt, and emotional burdens of mothers of children with Down syndrome and mothers of children with an undefined reason for their mental retardation, the latter group was found to be at a significant psychoemotional disadvantage.24 Therefore, defining an etiology goes beyond identifying recurrence risk and intervention planning; the process and its outcome may provide a significant emotional support to that family by addressing issues of guilt and in establishing connections with other similarly affected families through support groups.

MOST COMMON IDENTIFIABLE ETIOLOGIES

The three most common identifiable causes of mental retardation are fetal alcohol syndrome (FAS), the fragile X syndrome, and Down syndrome. In individual children with FAS, IQ measures range from 20 to 120, with a mean of 65.25 In comparison, IQ scores of affected male patients with the fragile X syndrome range from 25 to 65, and those of children with Down syndrome range from 40 to 60.26,27

Fetal Alcohol Syndrome

FAS is the most common preventable, nongenetic cause of mental retardation.28 Mental retardation is the abnormality most often associated with the diagnosis of FAS. Estimates of birth prevalence vary among countries. The critical period for alcohol exposure appears to be in the initial 3 to 6 weeks of brain development. The term fetal alcohol spectrum disorders has been suggested to describe the range of impairments in this disorder.29 Other terms such as fetal alcohol effects, prenatal alcohol effects, and alcohol-related neurodevelopmental disabilities or birth defects have been proposed.29 There is no reliable biological marker for FAS. Therefore, the diagnosis is based on clinical criteria that include evidence of prenatal and postnatal growth deficiency, characteristic facial features, and central nervous system anomalies and/or dysfunction.30 Although a history of maternal alcohol use during the pregnancy should be present, exposure is frequently underreported. The differences in growth and facial features vary with the patient’s age and ethnicity.25 Multiple efforts have been made at establishing a paradigm or tool to evaluate and diagnose these affected children, including the Institute of Medicine’s criteria for FAS/fetal alcohol effects published in 199628 and the four-digit system proposed by Astley and Clarren.31

In comparison with other individuals with an identifiable cause of mental retardation, FAS-affected children are at an increased risk for behavioral and psychiatric disorders. Children with FAS exhibit early deficits in measures of attention, learning, executive functioning, and visual-spatial processing. Their social abilities often plateau at the 6-year-old level. Individuals with FAS/fetal alcohol effects demonstrate significant problems with adaptive behavior, which continue into adulthood. One of the strongest correlates with this adverse outcome was the lack of an early diagnosis.32 Young adults with FAS and normal IQs (>70) demonstrate deficits in the areas of attention, verbal learning, and executive function that are more severe than suggested by IQ alone. FAS-affected children with normal IQ scores may still have significant neurobehavioral and adaptive deficits. Some of these behavioral issues may be complicated by the association between several forms of hearing loss and FAS: delays in auditory maturation, sensorineural hearing loss, and intermittent hearing loss secondary to chronic serous otitis media.

Fragile X Syndrome

The fragile X syndrome (also see Chapter 10B for more information) is the most common inherited form of mental retardation and has been identified in every racial and ethnic group studied. It is the leading cause of inherited mental retardation, affecting approximately 50,000 persons in the United States alone (prevalence, 1 per 4000 boys and men, 1 per 6000 girls and women). X-linked factors are believed to be responsible for 10% to 12% of mental retardation in boys and men.33 Fragile X represents the most common (15% to 25%) of the numerous loci identified on the X chromosome that are associated with mental retardation. The fragile X syndrome is the result of an expansion of an unstable cytosine-guanine-guanine (CGG) repeat within the FMR1 gene at Xq27.3. The reason for this expansion is unknown. Four allele patterns have been defined: normal (6 to 50 repeats), intermediate/“gray” (45 to 50), permutation (55 to 200) and full mutation (>200). Once the expansion reaches 200 repeats, the entire FMR1 gene region is methylated (silenced) and FMR1 protein is not produced. It is the absence of FMR1 protein that leads to the characteristic cognitive and clinical features of the syndrome.34

The cognitive profile in the fragile X syndrome is similar in both affected male and female patients, with observed weaknesses in the areas of short-term memory for complex sequential information, visual-spatial skills, planning, and verbal fluency. Many of these areas are often subsumed under the term executive functioning.35 In the fragile X syndrome, the social deficits that make up part of the full mutation phenotype range from autistic features to social anxiety and pragmatic language deficits. As many as 25% to 35% of individuals with full mutations meet diagnostic criteria for autism.36

Boys and men with the full mutation usually exhibit moderate to severe intellectual impairment, characteristic language disorders (cluttering; stronger receptive than expressive skills), and social and behavioral difficulties, including problems with attention, impulsivity, anxiety, social avoidance, and arousal. There does not appear to be any relationship between the number of CGG repeats and IQ score in boys and men with the full mutation. Boys and men with the fragile X syndrome exhibit a decline in cognitive, language, and adaptive skills measures during the school years. A specific cause of this decline is not known.26

Approximately 30% to 50% of girls and women with the full fragile X mutation have IQ scores in the mental retardation range. In addition, they often exhibit a characteristic behavioral phenotype of extreme shyness and decreased eye contact. The remaining female patients may present with borderline to normal intellectual functioning, learning disabilities related to executive functioning, and/or other psychosocial difficulties. There does appear to be a relationship between IQ score and chromosome X activation scores and between IQ score and FMR1 protein levels in affected women.37

The ability to identify children with the fragile X mutation through genetic testing is of particular benefit to physicians and families. DNA studies for the fragile X syndrome have been readily available since 1991 and should be strongly considered in every affected child, boy or girl, in whom the cause of mental retardation is unknown. Despite the availability of this technology, the average age at diagnosis in boys with the fragile X syndrome is 3 years; it is even later in girls.38 In a survey of 274 families with a child with the fragile X syndrome, a number of variables affected making the diagnosis of the syndrome in a timely manner.38 As is the case in other cause of developmental delay, there is often a lag between when the parent expresses concern and when the professional agrees that there is a problem. More than one half of the families expressing a concern about their child were told to “wait and see; he might improve” or that their child was developing normally. In families with affected children born after 1991, the average time between the parent’s first concern and the ordering of the fragile X test was 18 months. More than 50% of the families had already had another child before the diagnosis of fragile X syndrome was made.38 Although some authorities have argued for its implementation, the fragile X syndrome does not meet the traditional criteria for neonatal screening, because an identifiable intervention that could change the course of the disorder does not exist.

Down Syndrome

Down syndrome occurs in 1 per 800 live births and 1 per 1000 conceptions and is the most common genetic disorder causing mental retardation. It is usually readily identified at or near birth by characteristic physical features: hypotonia, hyperflexibility of joints, flat facial profile, slanted palpebral fissures, poor Moro reflex, excess skin on the back of the neck, abnormal ears, dysplasia of the midphalanx of the fifth finger, and a single palmar crease. Other frequently associated conditions include congenital heart disease (40%) and gastrointestinal abnormalities (5%).39 There exist artistic representations of persons with Down syndrome from as early as 500 A. D. Because no combination of these features is specific to Down syndrome, the diagnosis is confirmed by routine chromosome analysis; three abnormalities are possible. The most common finding on chromosomal analysis is a true trisomy for chromosome 21 (in 95% of affected patients); unbalanced robertsonian translocations (3% to 4%), and mosaicism (1% to 2%) account for the other affected individuals. Triplication of a specific region of the long arm of chromosome 21 (21q22.2) is sufficient to produce the clinical phenotype.40 Although there are many similarities in this group, individual variation must also be recognized. The range of outcome can be quite broad. Most affected patients have mild to moderate mental retardation. Mental retardation in children with Down syndrome is not an “across-the-board” phenomenon; thus, there are strengths, as well as deficits.

The profile of cognitive impairment in Down syndrome appears to differ from that of other forms of mental retardation. In much of the work involving children with Down syndrome, investigators have studied their language difficulties, especially in the areas of phonological, grammar, and syntactic skills. Expressive language skills are often more delayed than are cognitive and receptive language skills.40,41 There is also strong evidence that these patients have specific difficulties in other areas of learning and memory, such as poor verbal working memory. Affected individuals show relative strengths in visual motor skills. Although children with Down syndrome continue to learn new skills, they appear to be subject to instability of acquisition and rapid forgetting. Their rate of learning is not only delayed but appears to follow a different path.42 The measured IQ of individuals with Down syndrome typically declines through the first 10 years of life, reaching a plateau in adolescence that continues into adulthood.43,44 These functional deficits may be explained by differences in the hippocampal and prefrontal cortex regions of their brains.

Although fetal brains of individuals with Down syndrome are normal, they do not develop the increasing dendritic complexity or number seen in unaffected individuals.42 Delayed myelination of these structures is seen in 25% of children with Down syndrome. Anatomical studies have demonstrated neuropathological changes earlier than in the general population. Some of these changes are similar to those seen in association with Alzheimer disease. However, although 100% of individuals with Down syndrome eventually exhibit these changes, only 50% have clinical evidence of the associated dementia.42 Individuals with Down syndrome have behavioral and psychiatric problems but often less frequently than children with other types of mental retardation.40 From childhood and into adolescence, the most frequent problems are disruptive behavior disorders, including attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and oppositional defiant disorder. Approximately 5% to 10% also meet criteria for autism.45 As adults, individuals with Down syndrome are more likely to have a major depressive disorder or demonstrate aggressive behaviors.46

TIMING OF CAUSE

Prenatal

Most cases of mental retardation have prenatal causes: 70% of cases of severe mental retardation and 51% of cases of mild mental retardation.47 Children with birth defects, regardless of the type of defect, are significantly more likely to be identified with mental retardation than are children without birth defects; the risk tends to be the highest among children with central nervous system and heart defects.16 Environmental exposures during the prenatal period (e.g., to alcohol) and intrauterine infections (e.g., cytomegalovirus) also contribute to the overall incidence of mental retardation. Placental insufficiency for any variety of reasons may result in fetal malnutrition and subsequent intrauterine growth retardation; in the most significant cases of intrauterine growth retardation, affected infants demonstrate evidence of microcephaly at birth.

Perinatal

Individuals in this group are most often affected by the sequelae of low birth weight (<2500 g) and prematurity (<37 weeks of gestation). These complications represent about 4% of identifiable causes of severe mental retardation and 5% of identifiable cases of mild mental retardation. Perinatal infections, including herpes simplex virus and group B streptococcal infections, also often produce serious long-term cognitive effects.9

NATURE OF INSULT

Genetic

The number of known genetic causes of mental retardation now exceeds 1000 and represents the largest proportion of known causes of mental retardation (also see Chapter 10B). This number is expected to increase as genetic techniques, such as subtelomeric fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) and comparative genomic hybridization, evolve and the ability to identify specific entities associated with cognitive impairment improves.48,49 Genetic causes are currently believed to be responsible for 7% to 15% of all cases of mental retardation and for 30% to 40% of cases with known causes.50,51 When a specific cause can be identified, genetic causes are typically identified in 30% of patients with severe mental retardation and in 4% to 8% of patients with mild mental retardation.52

Teratogenic

In utero exposures to teratogenic agents such as valproic acid and hydantoin and the effects of maternal cigarette smoking are associated with an increased risk for mental retardation.52,53 The effects of intrauterine exposure to alcohol may manifest across a spectrum of clinical conditions: fetal alcohol syndrome, alcohol-related birth defects, and alcohol-related neurodevelopmental disorder.54 Postnatal exposure to agents such as lead, methyl mercury, and polychlorinated biphenyls is also of concern.

Infectious

Although the effects of many infectious causes have been dramatically reduced with improved prenatal care and the introduction of several vaccinations (rubella, Haemophilus influenzae), this category still is important when specific causes of mental retardation are considered. Although the human immunodeficiency virus continues to be of concern, the effectiveness of methods to reduce maternal fetal transmission may have lessened its effect.9

Psychosocial

In cases of mild mental retardation, low socioeconomic status, however it is measured, is strongly and inversely related to prevalence.9,52 In theory, this is related to a lack of opportunity and/or stimulation in the home environment. The logical extension of that theory is that these cases are therefore preventable if identified early. It is this conclusion that formed the basis for the initial development of Head Start and other early intervention programs (EIPs).

CLINICAL MANAGEMENT

Importance of Assessing All Developmental Domains

The evaluation of a child with any type of delay in development should begin with a broadly based assessment in which all functional areas, not just the identified area of concern, are considered. This approach is consistent with the American Academy of Pediatrics’ recommendation for pediatricians to survey and screen routinely and repeatedly for development.55 Cognitive deficits may initially manifest as delays in language or social skills. Mental retardation may not be the only reason for this pattern of delay, but it must be considered and not immediately discarded as a “rare” problem in children. Relying on only clinical observation or informal checklists without specific cutoff scores or validation may cause the clinician to overlook affected children, delaying both identification and intervention.55

The level of cognitive involvement may be of primary importance in defining what is “normal” for a particular child in other developmental areas as patterns of developmental delay are described. For example, if a child has delays in both cognitive and social skills, the clinician must determine whether these deficits are similar in level or disparate, which would suggest other possible explanations or diagnoses, such as autism spectrum disorder. The incidence of pervasive developmental disorders in children with mental retardation is between 8% and 20%.56 With the increasing efforts by numerous organizations to identify children with autism spectrum disorder at the earliest possible age, the confounding effect of cognitive delay may be inappropriately ignored or minimized.

Timing of Presentation

NATURE OF PARENTS’ CONCERNS

In every case, it is extremely important for medical providers to listen to and address the concerns of a parent or care provider. It is extremely rare for parents’ chief complaint to be “I think my child is mentally retarded.” Instead they may report their own, or perhaps a teacher’s, concern that the child is “immature.” A child may initially present with behavioral problems, being described as “stubborn” or “oppositional.” The child’s inconsistent performance on structured, multiple-step tasks may be presented as proof that the child could do the work if he or she wanted to. Judgmental decisions by adults that the child is “just lazy” without an effort to assess the child’s true abilities may further delay the diagnosis. Provider reassurances that the child “will grow out of it” or that he or she “looks fine to me” have repeatedly been shown to be significantly frustrating for parents seeking help for their child.57

THE EFFECT OF MENTAL RETARDATION SEVERITY ON MANIFESTATION

Severe mental retardation is often diagnosed by 1 year of age, especially when dysmorphic features are present. In addition, the effects of their associated medical conditions and the greater likelihood of global developmental delays, including motor delay, may explain their earlier identification.58

CLINICAL DIAGNOSIS

A number of misconceptions that have been identified over the years have delayed acknowledgment of “mental retardation” as an appropriate clinical possibility, by both parents and physicians: “cute children” cannot have mental retardation; “ambulatory children” cannot have mental retardation; children younger than a certain age are “too young to test.”59 When these and other barriers are finally overcome, the clinical diagnosis of mental retardation can be considered as a possible explanation for a child’s pattern of developmental differences. A comprehensive and appropriate assessment should then be initiated to confirm the diagnosis.

Establishing the Diagnosis of Mental Retardation with the AAMR Three-Step Assessment

STEP 1

Cognitive tests of infant and early childhood cognitive abilities, except in the most severely affected cases, are poor predictors of later academic success, an ability that is currently best represented by an IQ score. The developmental abilities of typical children in this age range are rapidly changing.60 IQ testing is possible during the preschool years; however, the label “mental retardation” is usually not applied until the child is of school age, because IQ tests are not well correlated with later measures of IQ until 3 to 5 years of age. At that point, formal IQ testing is more reliable, and results better reflect a child’s long-term abilities (see Chapter 7C for more information). Several frequently used instruments are briefly described in this chapter. Lichtenberger61 published a more detailed review of formal measures of preschool cognitive assessment. Whichever particular instrument is selected, it must match the purpose of the assessment: to establish eligibility for services, to assist in planning intervention strategies and programs, or to provide support benefits and/or legal protection. Interpretation of test results always requires careful consideration of several variables: Was this a typical performance for the child? Were all sociocultural biases considered during test development and administration? Did the child understand the test instructions/format? Were special modifications required because of other developmental disabilities (motor, sensory, communication deficits)?61

Bayley Scales of Infant Development-III: Provides a core battery of five sclaes. Three scales administered with child interaction—cognitive, motor, language. Two Scales conducted with parent questionnaires—social-emotional, adaptive behavior. Used in very young children (aged 1 to 42 months).62

Bayley Scales of Infant Development-III: Provides a core battery of five sclaes. Three scales administered with child interaction—cognitive, motor, language. Two Scales conducted with parent questionnaires—social-emotional, adaptive behavior. Used in very young children (aged 1 to 42 months).62 Stanford-Binet Intelligence Scale (5th edition): Provides a full scale score, two domain scores (verbal and nonverbal IQ), and several factor indexes for individuals aged 2 to 85 years.63

Stanford-Binet Intelligence Scale (5th edition): Provides a full scale score, two domain scores (verbal and nonverbal IQ), and several factor indexes for individuals aged 2 to 85 years.63 Kaufman Assessment Battery for Children II: Provides a global measure of ability (Mental Processing Composite IQ) for children as young as 3 years old. Additional scales and indices are added across the age range of the instrument (3 years 0 months to 18 years 11 months).64

Kaufman Assessment Battery for Children II: Provides a global measure of ability (Mental Processing Composite IQ) for children as young as 3 years old. Additional scales and indices are added across the age range of the instrument (3 years 0 months to 18 years 11 months).64 Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence III (WPPSI III): Provides Full Scale, Verbal, and Performance scores (FSIQ, VIQ, and PIQ). The latest edition (2002) adds a General Language Composite for measuring both expressive and receptive but not higher order language functioning. For older children (aged 4 years 0 months through 7 years 3 months), a Processing Speed Quotient has been added. The WPPSI III is an appropriate instrument for children aged 2 years 6 months to 7 years 3 months.65

Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence III (WPPSI III): Provides Full Scale, Verbal, and Performance scores (FSIQ, VIQ, and PIQ). The latest edition (2002) adds a General Language Composite for measuring both expressive and receptive but not higher order language functioning. For older children (aged 4 years 0 months through 7 years 3 months), a Processing Speed Quotient has been added. The WPPSI III is an appropriate instrument for children aged 2 years 6 months to 7 years 3 months.65 Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children (WISC-IV): Provides Verbal, Performance, and Full Scale IQ scores for children aged 6 years to 12 years.66

Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children (WISC-IV): Provides Verbal, Performance, and Full Scale IQ scores for children aged 6 years to 12 years.66STEP 2

Step 2 is to describe strengths and weaknesses across the five dimensions of mental retardation.

Describing strengths and weaknesses represented a dramatic shift for the AAIDD and other organizations working with individuals with mental retardation. These organizations began to address the effect of mental retardation on such individuals and on society, focusing on intervention and service planning rather than simply a “level of severity” classification system approach. These five dimensions are a key component of the 2002 AAMR comprehensive model of mental retardation (see Table 11-3). (See also the section “Levels of Support” earlier in this chapter.)

STEP 3

Step 3 is to determine needed supports and classify by intensity of service.

In a supports-based approach to the delivery of necessary services, the individual, rather than a specific program, is the focus. Supports enhance functioning and facilitate an individual’s inclusion in his or her natural community. Characterizing a person’s strengths and weaknesses is of no benefit unless some additional effort is made to define the necessary intensity level of those supports. It is important to recognize that the intensity of supports is independent of the location where the support needs to be delivered and may vary across the various areas of need. The judicious use of supports should improve a person’s level of functioning. Specific levels of support intensity have been defined (see Table 11-4). (See also the section “Levels of Support” earlier in this chapter.)

Identifying strengths and weaknesses across the five dimensions was integrated with the concept of “levels and intensity of support” in the AAIDD’s Supports Intensity Scales.10 There is frequent confusion about how the Supports Intensity Scales differ from a standardized measure of adaptive skills. A key distinction between the two approaches is that adaptive behavior measurements address “skills” needed for an individual to successfully function in society (the level of mastery), whereas the Supports Intensity Scales address activities that a person engages in during the course of participating in everyday life and how much support he or she needs to complete those activities.11

Etiological Diagnostic Workup: “The Search”

OVERVIEW: WHY ASK “WHY?”

Lenhard and associates24 described a number of psychological benefits for families attributed to diagnostic certainty. Families were frequently confronted in their physician’s office with an approach that Lenhard and associates characterized as “diagnostic minimalism”—the argument of health care providers that the assignment of a diagnosis of mental retardation rarely led to more effective treatments. The reluctance of physicians and other professionals (i.e., school personnel) working with the child and family to make and discuss this diagnosis may eliminate essential pathways to facilitate the family’s coping. It is also much easier for parents of children with a specific diagnosis to join and form associations and provide mutual support. Having a name for their child’s condition may improve the family’s access to systems of public support.

There is no standard workup for mental retardation or global developmental delay. There are numerous consensus guidelines regarding the appropriate degree and order of assessment in children diagnosed with mental retardation: two from genetics organizations, one from the American Academy of Neurology, and one from the American Academy of Pediatrics.50,51,70,70a A useful comparison of the similarities and differences among these statements was included in the article by Roberts and colleagues.71

COMPONENTS OF THE SEARCH

Each series of investigations should be tailored to the individual patient. The investigation should be directed by findings from the patient’s history, the family history, and the physical examination. In a systematic analysis, van Karnebeek and associates72 reported the results of several diagnostic investigations. Their recommendations included obtaining a clinical history and physical examination with emphasis on the neurological and dysmorphological examinations, obtaining standard cytological studies in all cases, ordering fragile X studies in all male patients, and requesting FISH subtelomeric studies based on established checklists. Metabolic studies were not recommended as a first-line investigation. Van Karnebeek and associates also concluded that neuroradiological studies had a high yield for identifying brain anomalies but a low yield for establishing an etiological diagnosis.72

HEARING AND VISION EVALUATIONS

Individuals with developmental delay and/or mental retardation are at increased risk for primary sensory impairments: vision abnormalities in 13% to 50% and audiological abnormalities in 18%.51 Formal assessments of hearing and vision are an integral part of the evaluation of these children.

GENETIC TESTING: INDICATIONS AND YIELD

Cytogenetically visible rearrangements are present in about 1% of newborns with a standard karyotype study (500 bands). The clinical significance of these rearrangements is not known. Chromosomal abnormalities are seen in approximately 25% of individuals with mental retardation: 40% of cases of severe mental retardation and 10% of cases of mild mental retardation. The presence of two or more minor dysmorphic features detected on physical examination also increases the likelihood that a chromosomal abnormality will be identified from 3.7% to 20% in affected individuals. The fragile X has been identified in 2% to 6% of male patients and in 2% to 4% of female patients with mental retardation. An increase in diagnostic yield from 2.6% to 7.6% is seen when decisions to obtain DNA fragile X studies are combined with physical examination findings.21

There is an increased percentage of genes in the telomeric regions of the chromosomes. Currently, these areas can best be examined with FISH. This technique identifies differences in 0.9% of normal controls, 1.1% of individuals with mild mental retardation, and 6.6% of individuals with moderate to severe mental retardation. At some point in the future, subtelomeric abnormalities may well become the primary cause of what had previously been described as “idiopathic mental retardation.” A checklist has been developed to improve the diagnostic yield of this method: family history of mental retardation; prenatal onset of growth retardation; postnatal poor growth/overgrowth; two or more facial dysmorphic features; and one or more nonfacial dysmorphic features and/or congenital abnormalities. The most significant predictors of a subtelomeric deletion are intrauterine growth retardation and a family history of mental retardation.73

NEUROIMAGING: INDICATIONS AND YIELD

There is an increased chance of an abnormal finding on head imaging study in the presence of an IQ of less than 50 in a child who has one of the following: microcephaly or macrocephaly, an abnormal cranial contour, midline and/or multiple dysmorphic features, an abnormal neurological examination finding, seizures, neurocutaneous findings, or a history of developmental milestone loss.74,75 Both the American College of Medical Genetics and the American Academy of Neurology recognize these as indications for obtaining a head imaging study. The American Academy of Neurology also recommends a head imaging study in cases of mental retardation associated with intrapartum asphyxia.50,51,58 The current yield from head imaging studies in children with mental retardation ranges from 33% in children without any other signs or symptoms to 63% to 73% in children with both mental retardation and cerebral palsy.21,51

METABOLIC TESTING: INDICATIONS AND YIELD

Relatively few metabolic conditions cause mental retardation in isolation; other neurological symptoms are commonly found (see Chapter 10C for more information). The presence of such symptoms in the child and in family members should be pursued. Many researchers assessing the yield of routine metabolic investigations in the child with mental retardation have concluded that there is little usefulness in such screening.50,51,70 The presence of a positive family history or other specific signs and symptoms identified in the history and physical examination may increase the yield of metabolic screening from 1% to 5%.

Generally accepted indications for additional metabolic investigations in children with mental retardation include episodic vomiting or lethargy, poor growth, seizures, evidence of storage disease, unusual odors, the loss of or a plateau of developmental skills, the presence of a movement disorder (chorea, dystonia), a new sensory loss (especially with retinal abnormality), or an acquired cutaneous disorder. The yield of directed and focused metabolic testing that is based on symptoms and performed in a stepwise manner may approach 14%.76

Expanded neonatal screening, now available in 23 states in the United States, tests for 20 or more of the 29 conditions recommended by the American College of Medical Genetics.77,78 The expansion in neonatal screening has allowed for the identification and treatment of inborn errors of metabolism in many children who might otherwise have died with the conditions undetected or become handicapped before any therapeutic interventions could be initiated. Although 15 states screen for fewer than 10 conditions, screening for congenital hypothyroidism and phenylketonuria is universal. Information from these screening programs should always be included in the evaluation of a child suspected to have mental retardation.