CHAPTER 22 Cloaca

Step 1: Surgical Anatomy

♦ Cloacal anomalies occur in about 1 in 20,000 live births. They occur exclusively in girls and are the most common defect in female patients, after perineal fistulas and vestibular fistulas. Persistent cloaca was, in the past, considered an unusual defect with a high incidence of rectovaginal fistulas reported in the literature. In retrospect, it seems that cloaca is a much more common defect than reported, as imperforate anus with rectovaginal fistula is an almost nonexistent defect, occurring in less than 1% of all cases. Therefore, most patients with persistent cloaca were probably erroneously thought to have a rectovaginal fistula. Many of those patients underwent operations to correct the rectal component of the malformation leaving them with a persistent urogenital sinus.

♦ The major goals of treatment for cloaca include the achievement of bowel control, urinary control, and sexual function.

Classification

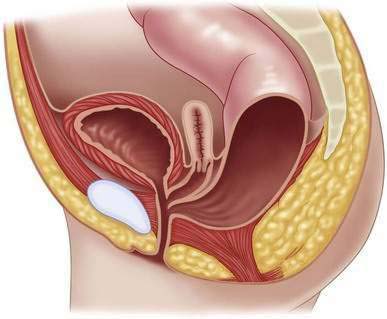

♦ In cloacal malformations, the length of the common channel (Fig. 22-1) varies from 1 to 10 cm, which has important technical and prognostic implications. When the common channel is shorter than 3 cm, patients usually have a well-developed sacrum and good sphincters. In contrast, a cloaca with longer than 3-cm common channel typically is a more complex defect, often with a poor sphincter mechanism and sacrum.

Step 2: Preoperative Considerations

♦ The diagnosis of persistent cloaca is a clinical one. Careful separation of the labia discloses a single perineal orifice, which is pathognomonic for a cloaca (Fig. 22-2). These patients often have small external genitalia. Sometimes patients with cloaca have a palpable lower abdominal mass that represents a distended vagina (hydrocolpos). Failure to recognize the presence of a cloaca in a neonate may be dangerous because more than 90% of these patients have significant associated urologic problems.

Management of Cloacal Malformations During the Neonatal Period

♦ Once the clinical diagnosis of a cloaca has been established, the next step is to perform a rapid urologic evaluation. Abdominal ultrasonography is the most important screening test to rule out the presence of hydronephrosis, hydroureter, or hydrocolpos.

♦ In more than 30% of these cases, the vagina is abnormally distended with mucous secretions and urine (hydrocolpos). The distended vagina may compress the trigone to interfere with the drainage of the ureters and can potentially produce megaureters. The most common error at this stage is to perform only a colostomy in a patient with severe obstructive uropathy, which can lead to acidosis and urinary sepsis. The dilated vagina can also become infected (pyocolpos), and this can lead to vaginal perforation and peritonitis. Such an enlarged vagina may ultimately represent a technical advantage at the time of the definitive repair because of the more abundantly available vaginal tissue for reconstruction.

♦ If a hydrocolpos is correctly identified and drained, obstruction of the urinary tract is usually relieved, thus making urinary diversions such as a vesicostomy, ureterostomy, or nephrostomy unnecessary. Rarely a near-atresia of the urethra exists and a vesicostomy may be required. Drainage of the hydrocolpos can be done by suturing it to the abdominal wall as a small stoma or by placing a transabdominal curled tube.

♦ Attempts to drain the urinary tract or hydrocolpos through the single perineal orifice (common channel) by way of intermittent catheterization or dilatations are not recommended because it is unpredictable whether the catheter will enter the bladder or the vagina. This can be the case particularly with long common channels. Blind dilatations of the single external orifice may also provoke local damage that can interfere with the future repair.

Associated Defects

Müllerian Anomalies

♦ Some of these patients may also suffer from cervical or vaginal atresias or stenoses. When undetected, these may interfere with the drainage of menstrual blood during puberty. These patients can develop hematometra, hematocolpos, or intra-abdominal pseudocysts from retrograde menstruation.

Cloacagram

♦ After the patient has recovered from the colostomy, high-pressure distal colostography as well as injection of contrast through the single perineal orifice and vaginotomy tube or vesicostomy, if present, will help define the cloacal anatomy as well as delineate the location of the rectum, vaginas, or hemivaginas, and vesicoureteral reflux. It is a vital study to help plan the definitive repair. This study can be done in three-dimension, which gives a clear view of the interrelationships of structures.

Step 3: Operative Steps

Endoscopy

♦ An endoscopy is recommended in infants with cloaca to determine the anatomy. The specific purpose of this procedure is to determine the length of the common channel. A separate anesthetic to do this endoscopy within 1 to 3 months of life is the ideal time for this investigation. We avoid endoscopy in the newborn period because it requires a tiny scope, does not afford great visualization, and is difficult because the perineum is often swollen.

♦ Two well-characterized groups of patients with cloaca exist (Table 22-1). These two groups represent different technical challenges and must be preoperatively recognized. The first group includes patients who are born with a common channel shorter than 3 cm. Fortunately they represent the majority of cloacas and usually can be repaired with a posterior sagittal approach only, without a laparotomy. The second group includes patients with longer common channels. These patients usually need a laparotomy, followed by a decision-making process involving vaginal replacement techniques and urologic reconstruction planning that requires considerable experience and special training in urology. It is ideal if these patients are referred to centers dedicated to the repair of these defects.

Table 22-1 Comparison of Two Groups of Patients with Cloaca

| GROUP A | GROUP B | |

|---|---|---|

| Common channel | <3 cm | >3 cm |

| Type of operation | Posterior sagittal approach alone | Posterior sagittal and laparotomy |

| Length of procedure | 3 hours | 6-12 hours |

| Hospitalization | 48 hours | Several days |

| Associated urologic defects | 59% | 91% |

| Incidence in our series | 62% | 38% |

| Voluntary bowel movements | 68% | 44% |

| Urinary continence | 72% | 28% |

| Average number of operations* | 9 | 18 |

| Intraoperative decision-making | Relatively easy, reproducible operation | Complex, delicate, technically demanding** |

* Including orthopedic, urologic, cardiac, and general

** Bladder vagina separation, ureteral catheterization, ureteral re-implantation, vesicostomy, cystostomy, bladder neck reconstruction or closure, vaginal switch, vaginal replacement, (using rectum, colon, small bowel)

Colostomy

♦ It is imperative to perform the colostomy proximal enough so that it does not interfere with the future definitive repair. Specifically, the surgeon must leave enough redundant, distal rectosigmoid to allow a pull-through and for potential use of colon for vaginal replacement. (See the colostomy section in Chapter 21).