Daniel W. Cramer

Study Designs

Medical practice is evolving to include complex options for patient treatment and preventive care, in part because clinical research methods and techniques to guide patient care have advanced. To evaluate whether new treatments and diagnostic approaches should be integrated into clinical practice or decide whether observational data reported in the literature is relevant, clinicians should understand the fundamental strengths and limitations of clinical research methods and the level of evidence different types of studies provide.

As outlined by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, clinical research includes patient-oriented research involving understanding mechanisms of human disease, studies of therapies or interventions for disease, clinical trials, and technology development.

Epidemiologic methods and behavioral research are used in clinical research to examine the distribution of disease and the factors that affect health and how people make health-related decisions. Outcomes research and health services research include studies that seek to identify the most effective and efficient intervention, treatments, and services for patient care (1).

The purpose of a research study is to test a hypothesis about and to measure an association between exposure (or treatment) and disease occurrence (or prevention). The type of study design influences the way the study results should be interpreted.

Analytic studies are often subdivided into experimental studies (clinical trials) and observational studies (cohort studies, case-control studies, and cross-sectional studies).

Descriptive studies (case reports and case series) often provide useful information for informing future analytic studies.

The common types of clinical research study methods, considerations for the strength of evidence for the specific study design, and interpretation of the results are presented. Although there is debate about which system should be used for evaluating the strength of evidence from an individual study, a well-designed and executed clinical trial presents the highest level of evidence (2). Other types of studies should be designed to best approach the strengths of a clinical trial.

Clinical Trials

Clinical trials include intervention studies where the assignment to the treatment or control condition is controlled by the investigator and the outcomes to be measured are clearly defined at the time the trial is designed. Features of randomized clinical trials include randomization (in which participants are randomly assigned to exposures), unbiased assessment of outcome, and analysis of all participants based on the assigned exposure (an “intention to treat” analysis).

There are many different types of clinical trials, including studies designed to evaluate treatments, prevention techniques, community interventions, quality-of-life improvements, and diagnostic or screening approaches (3). Since 2007, investigators conducting randomized clinical trials are expected to register the trial to comply with mandatory registration and results reporting requirements (4).

Clinical Trial Phases

New investigational drugs or treatments are usually evaluated by clinical trials in phases with more people being involved as the purpose of the study becomes more inclusive (3).

Phase I Trials In these trials, researchers test an experimental drug or treatment for the first time in a small group of people (20–80) to evaluate its safety, determine a safe dosage range, and identify side effects.

Phase II Trials In these, the experimental study drug or treatment is given to a larger group of people (100–300) to see whether it is effective and to further evaluate its safety.

Phase III Trials In phase III trials, the experimental study drug or treatment is given to large groups of people (1,000–3,000) to confirm its effectiveness, monitor side effects, compare it to commonly used treatments, and collect information that will allow the experimental drug or treatment to be used safely.

Phase IV Trials These are postmarketing studies that delineate additional information, including the drug’s risks, benefits, and optimal use.

Randomized Controlled Double-Blinded Clinical Trial

The randomized controlled double-blinded clinical trial is considered the gold standard for evaluating interventions because randomizing treatment assignment and blinding both the participant and the investigator are the cornerstones for minimizing bias. When studies are not randomized or blinded, bias may result from preferential assignment of treatment based on patient characteristics or an unintentional imbalance in baseline characteristics between treatment groups, leading to confounding.

Although not all studies can be designed with blinding, the efforts used in the trial to minimize bias from nonblinding should be explained. Investigators are expected to provide evidence that the factors that might influence outcome[MB1], such as age, stage of disease, medical history, and symptoms, are similar in patients assigned to the study protocol compared with patients assigned to placebo or traditional treatment. Published reports from the clinical trial are expected to include a table showing a comparison of the treatment groups with respect to potential confounders and to demonstrate that the groups did not differ in any important ways before the study began.

CONSORT Checklist

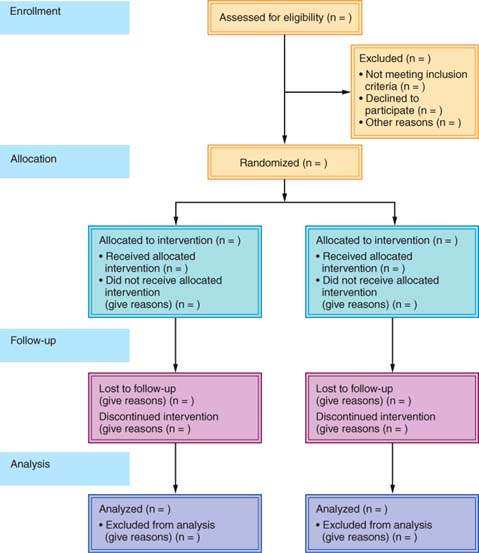

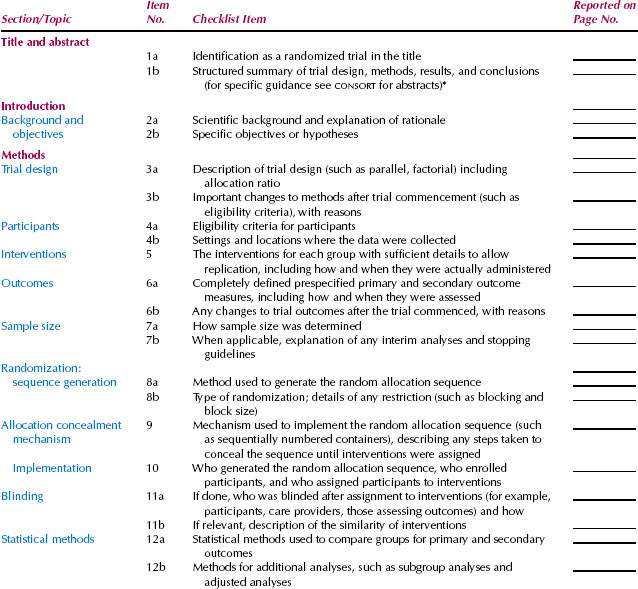

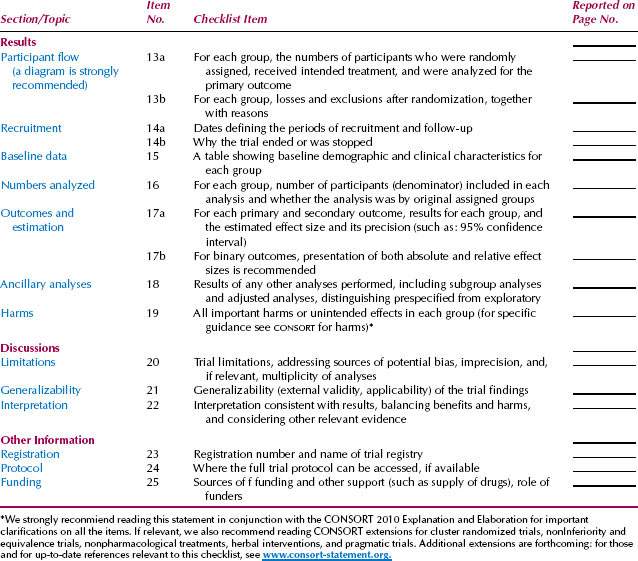

Clearly defining the outcome or criteria for successful treatment helps ensure unbiased assessment of the outcome. A well-designed clinical trial has a sufficient number of subjects enrolled to ensure that a “negative” study (one that does not show an effect of the treatment) has enough statistical power to evaluate the predetermined (a priori), expected treatment effect. The Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) Statement is an evidence-based, minimum set of recommendations for reporting on randomized controlled trials developed by the CONSORT Group to alleviate the problems arising from inadequate reporting of randomized controlled trials. The 25-item CONSORT checklist (Table. 4.1) and flow diagram (Fig. 4.1) offer a standard way for authors to prepare reports of trial findings, facilitating their complete and transparent reporting and aiding their critical appraisal and interpretation (5).

Figure 4.1 CONSORT flow diagram.

Table 4.1 CONSORT checklist.

Clinical Trial Design Considerations

Clinical trials are considered a gold standard, because when done well they provide information about both relative and absolute risks and minimize concerns about bias and confounding (see the section on Presenting and Understanding the Results of Analytic Studies). Many clinical research questions are not amenable to clinical trials because of cost restraints, length of time required to complete the study, and feasibility of recruitment and implementation.

When evaluating the results from a clinical trial, consider how restrictive inclusion and exclusion criteria may narrow the participant population to such a degree that there may be concerns about external validity or generalizing the results. Other concerns include blinding, loss to follow-up, and clearly defining the outcome of interest. When the results of a randomized controlled trial do not show a significant effect of the treatment or intervention, the methods should be evaluated to understand what assumptions (expected power and effect size) were made to determine the necessary sample size for the study.

Intention-to-Treat Analysis

Randomized controlled trials should be evaluated with an intention-to-treat analysis, which means that all of the people randomized at the initiation of the trial should be accounted for in the analysis with the group to which they were assigned. Unless part of the overall study design, even if a participant stopped participating in the assigned treatment or “crossed over” to another treatment during the study, they should be analyzed with the group to which they were initially assigned. All of these considerations help to minimize bias in the design, implementation, and interpretation of a clinical trial (6).

Observational Studies

In cases where the exposure and outcome are not amenable to an experimental design, because the exposure is known or suspected to have harmful effects, observational studies may be used to assess association. Observational studies, including cohort, case-control, and cross-sectional studies, are analytic studies that take advantage of “natural experiments” in which exposure is not assigned by the investigator; rather, the individuals are assessed by the investigator for a potential exposure of interest (present or absent) and outcomes (present or absent). The timing of the evaluation of the exposure and outcome defines the study type.

Cohort Studies

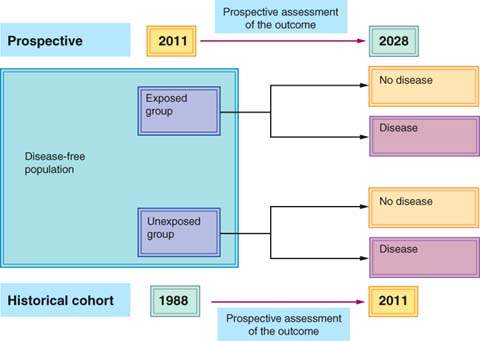

Cohort studies often are referred to as longitudinal studies. Cohort studies involve identifying a group of exposed individuals and unexposed individuals and following both groups over time to compare the rate of disease (or outcome) in the groups. Cohort studies may be prospective, meaning that the exposure is identified before outcome, or retrospective, in which the exposure and outcome have already occurred when the study is initiated. Even in a retrospective cohort study, the study is defined by the fact that the cohorts were identified based on the exposure (not the outcome), and individuals should be free of disease (outcome) at the beginning time point for the cohort study (Fig. 4.2).

Figure 4.2 Schematic of prospective and retrospective cohort study designs.