Chapter 35 Climacteric

MENOPAUSE AND PERI- AND POSTMENOPAUSE∗

Hormonal Changes

Hormonal Changes

Menopause rarely occurs as a sudden loss of ovarian function. For some years before menopause, the ovary begins to show signs of impending failure. Anovulation becomes common, with resulting unopposed estrogen production and irregular menstrual cycles (see Chapter 33). On occasion, heavy menses, endometrial hyperplasia, and increasing mood and emotional changes may occur. In some women, hot flashes (or flushes) and night sweats begin well before menopause is reached. These perimenopausal symptoms may last 3 to 5 years before there is complete loss of menses and postmenopausal levels of hormones are reached.

Ovarian Senescence

Ovarian Senescence

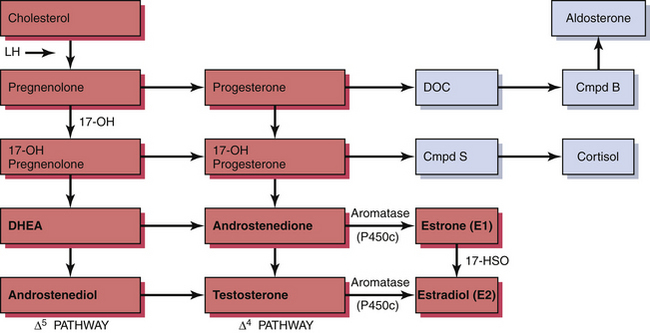

The ovary produces a sequence of hormones during a normal menstrual cycle. Under the influence of luteinizing hormone (LH), cholesterol from the liver is used to produce the androgens androstenedione and testosterone in the theca cells of the ovarian follicle. They, in turn, are converted in the granulosa cells immediately surrounding the oocytes into estrogen. Following ovulation, the luteal cells (luteinized granulosa cells) manufacture and secrete progesterone as well as estrogen. The synthesis of these sex hormones depends on the presence of viable follicles and ovarian stroma and the production of follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and LH in adequate amounts to induce their biosynthetic activity. The ovarian and adrenal (for comparison) steroid biosynthetic pathways are depicted in Figure 35-1.

Clinical Manifestations

Clinical Manifestations

Loss of estrogen is associated with urogenital atrophy and osteoporosis (Table 35-1). Although postmenopausal women have a higher incidence of heart disease and of cancer, the relationship between these adverse events and reduced endogenous estrogen production, as well as the effects of hormonal therapy on them, remains unclear and controversial.

TABLE 35-1 CONSEQUENCE OF ESTROGEN LOSS

| Symptoms (early) | |

| Physical changes (intermediate) | |

| Diseases (late) | Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|