Blood or serum

Complete blood count

Serum albumin

Erythrocyte sedimentation rate

C-reactive protein

Serologies

Anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody

Anti-Saccharomyces cerevisiae antibody

Antibodies to outer membrane porin

Antibodies to flagellin

NOD2 genetics (principally used in research studies)

Radiographic studies

Barium contrast radiography

Abdominal computed tomography

Abdominal magnetic resonance imaging

Radionuclide scintigraphy with Tc99 labeled white blood cells

Endoscopy and histology

Upper endoscopy with biopsies

Colonoscopy with biopsies

Video capsule endoscopy

Distinguishing Acute Self-Limited Colitis from IBD Involving the Colon

It is now recognized that our current culture methods are capable of identifying only a small subset of microorganisms that inhabit the intestine, and we cannot reliably culture all pathogens from a stool sample. In addition, a small number of documented cases of infectious colitis last longer than 30 days [5, 6]. Therefore, not every patient with bloody diarrhea and negative stool cultures has inflammatory bowel disease as the cause of their colitis. Epidemiologists utilize strict criteria (e.g., bloody diarrhea for over 6 weeks, or greater than two episodes of colitis within a 6-month period) to determine if a patient has ulcerative colitis [7, 8]. However, the practicing clinician does not wish to wait 6 weeks or longer to determine whether or not to treat the patient for IBD. Thus, in children with bloody diarrhea and negative stool cultures, performance of colonoscopy with random biopsies for histology early in the course of suspected IBD is important. Certain clinical and laboratory parameters (including chronic history of gastrointestinal complaints, growth failure, perianal tags, abnormal liver function tests, family history of IBD, and iron deficiency anemia) strengthen the argument for early colonoscopy in the individual patient. In contrast, other findings (fever, positive fecal leukocytes or calprotectin) can be seen in both IBD and infection [9]. It is also important to remember that a patient may have laboratory finding suggestive of infection, and also have new onset IBD. The new, ultrasensitive C. difficile PCR test has been particularly problematic in this regard, as the test is so sensitive it may not be able to differentiate between C. difficile colonization and C. difficile infection in the IBD patient [10].

Studies suggest that colonoscopy with careful examination of biopsy samples will allow differentiation between ASLC and IBD. In a cohort of 114 adults with acute colitis of less than 5 days duration, Mantzaris et al. performed colonoscopy at disease onset and subsequent flexible sigmoidoscopies at 1, 3, 6, and 18–24 months after initial illness. At 12 months after the onset of illness, a total colonoscopy was performed. Ultimately 68 patients were diagnosed with ASLC, and 46 patients were diagnosed with IBD (42 UC, 4 Crohn ileocolitis). Patients with UC had a significantly higher prevalence of diffuse erythema (100% vs. 25%), granularity (100% vs. 8%), and friability (100% vs. 12%) than patients with ASLC; in contrast, patients with self-limited colitis had a significantly higher prevalence of patchy erythema and microaphthoid lesion [11]. Histologic features identified reported in chronic inflammatory bowel disease but not in ASLC include: basal plasmacytosis, basal lymphoid aggregates, crypt branching, crypt atrophy, and the presence of Paneth cells in the left colon [6, 11–13]. Other findings, such as focal crypt destruction or superficial aphthous lesions, do not reliably differentiate between ASLC and IBD [14]. In one pediatric study, 8 of 29 patients with focal active colitis (cryptitis with an adjacent increase in lamina propria macrophages and T lymphocytes) were ultimately diagnosed with Crohn disease [15]. In another more recent study of focal active colitis in 90 adults, medications (NSAIDs) and infection were the most common causes, but 15% of patients who initially presented with focal active colitis on biopsy went on to develop IBD [16].

In summary, in a patient with bloody diarrhea and negative stool cultures, the performance of colonoscopy with random biopsies throughout the colon may provide the clinician and pathologist with evidence that proves or disproves the diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease. Endoscopic findings suggesting IBD include erythema, granularity, and friability, and histologic evidence supporting an IBD diagnosis include crypt distortion, crypt branching, and basal lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate. While the patient with focal active colitis on biopsy has a 15–25% chance of developing IBD over time, this histologic finding alone is not enough to make a diagnosis.

Distinguishing Ulcerative Colitis from Crohn Disease

Endoscopy and Biopsy

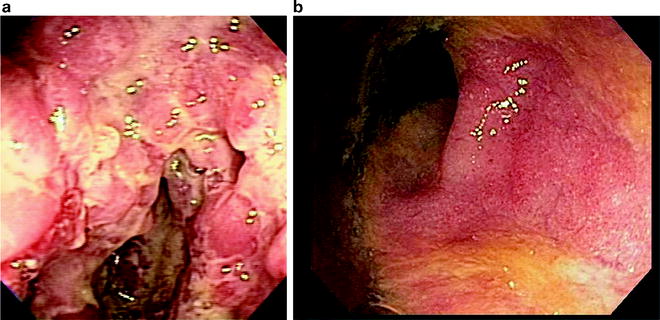

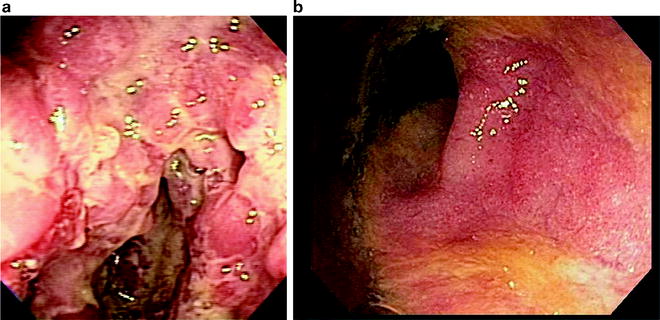

It is usually straightforward in most patients to differentiate UC from CD on colonoscopy. In most cases of Crohn disease, the inflammation is limited to the ileum, cecum, and ascending colon. In contrast, classic ulcerative colitis typically begins in the rectum, extends proximally, is in a diffuse continuous distribution, and does not involve the small bowel. Even if Crohn disease is limited to the colon, the endoscopic appearance will help differentiate the two diseases; Crohn disease is characterized by aphthae, deep fissures, and cobblestoning, while UC is characterized by superficial inflammation, granularity, and friability (Fig. 15.1a, b). Evidence of ileal stenosis or ulceration, perianal disease, or granulomatous inflammation also helps establish the diagnosis of Crohn disease. Clinical, endoscopic, and histologic features that assist the clinician in differentiating these two conditions were summarized by the ESPGHAN Porto working group, and are given in Table 15.2 [1].

Fig. 15.1

(a) Crohn disease of the colon—note the deep fissuring ulcers and discontinuous inflammation. (b) Ulcerative colitis—granularity, friability, and loss of vascular pattern

Table 15.2

Endoscopy and histology in inflammatory bowel disease—the Porto criteria

Crohn disease | Ulcerative colitis | |

|---|---|---|

Endoscopy (and visualization of oral and perianal regions) | Ulcers (aphthous, linear, or stellate) | Ulcers |

Cobblestoning | Erythema | |

Skip lesions | Loss of vascular pattern | |

Strictures | Granularity | |

Fistulas | Spontaneous bleeding | |

Abnormalities in oral or perianal regions | Pseudopolyps | |

Segmental distribution | Continuous with variable proximal extension from rectum | |

Histology | Submucosal or transmural involvement | Mucosal involvement |

Ulcers: crypt distortion | Crypt distortion | |

Crypt abscess | Crypt abscess | |

Granulomas (non-caseating, non-mucin) | Goblet cell depletion | |

Focal changes (within biopsy) | Mucin granulomas (rare) | |

Patchy distribution (biopsies) | Continuous distribution |

However, a subset of patients with IBD involving the colon will have certain “non-classical” features that may make the clinician less certain as to whether the patient has ulcerative colitis or Crohn disease. These are summarized in Table 15.3; all of these findings have been reported in ulcerative colitis. While it may be tempting to give a patient a diagnosis of “indeterminate colitis” if a patient has any of these atypical features, such a diagnosis makes it more difficult to enter such a patient into clinical trials or epidemiologic registries. Therefore, the author of this chapter suggests that a physician classify such a patient as ulcerative colitis, document the non-classical finding, and follow up the patient to see if the finding resolves or evolves over time. Some of these non-classical findings (ileitis, gastritis, periappendiceal inflammation, rectal sparing, and “patchy” histology) are discussed in more detail below.

Table 15.3

Nonclassical findings at presentation in UC patients, which do not exclude the diagnosis of UC

1.Clinical |

Small anal fissures or skin tags (<5 mm in size) |

Oral ulcers |

Growth impairment |

Diarrhea without macroscopic or microscopic blood |

2.Endoscopic |

Gastritis without aphthae |

“Backwash ileitis”—ileal erythema without linear ulceration |

Periappendiceal inflammation in a patient without pancolitis |

Rectal inflammation less severe than in the more proximal colon (relative rectal sparing) |

3.Histologic |

Microscopic ileitis without granuloma |

Microscopic gastritis without granuloma |

“Relative rectal sparing” (histologic inflammation less severe in the rectum). |

“Patchiness” (normal colonic mucosa in between two areas of colonic inflammation) |

“Backwash Ileitis” vs. Crohn of the Ileum

The term “backwash ileitis” was originally used to describe an abnormal appearance of the terminal ileum observed radiologically or endoscopically in patients with ulcerative pancolitis. The term derives from the original contention that the ileitis resulted as a reaction to “the reflux of colonic contents into the terminal ileum.” Currently such ileitis in UC is considered to be primary ileal mucosal inflammation. The prevalence of backwash ileitis in both children and adults has been evaluated in several studies. The most comprehensive study in adults was performed by Heuschen et al., who evaluated 590 adults with UC undergoing colonic resection. In this study 107 of 476 patients with pancolitis (22%) had evidence of backwash at colectomy; in contrast, backwash ileal inflammation was not seen in any patients with left sided ulcerative colitis [17]. The prevalence of backwash is similar in children [18].

In backwash ileitis, radiographic studies of the terminal ileum demonstrate a normal caliber ileum without stenosis or cobblestoning; however, a rough “sandpaper” appearance may be present in the terminal ileum [17, 19, 20]. At endoscopy a patient with backwash ileitis has a normal ileocecal valve without signs of stricture, stenosis, or ulceration. In backwash ileitis, normal lymphoid nodules may be present, but no linear ulcerations, deep fissures, or areas of cobblestoning are seen.

The histology of backwash ileitis, and what specific features differentiate this entity from CD of the ileum, remain unclear. Studies suggest that changes seen in “backwash ileitis” are usually mild, consisting of villous atrophy, increased mononuclear cells, and scattered crypt abscesses [21]. In contrast, Crohn disease of the ileum may be characterized by: “discrete transmural lymphoid aggregates,” “segmental bowel involvement,” or “non-necrotizing granulomas” [22].

Some investigators have automatically classified a patient as having Crohn disease or indeterminate colitis if there is any histologic inflammation on an ileal biopsy [23, 24]. This approach is probably overly conservative. Two recent case–control studies compared patients with backwash ileitis and matched controls, and suggest no difference in long term pouch outcomes after colectomy [22, 25]. In the larger study, prevalence of pouchitis (about 35%) was comparable in both the backwash and non-backwash group, as was the prevalence of fistulae around the pouch (around 10%) [22]. In the opinion of the NASGHAN working group, identification of nonspecific or microscopic ileitis in a patient with typical features of UC does not warrant a change of diagnosis, unless there are specific features suggesting Crohn disease (e.g., linear ulcers, cobblestoning, or granulomas). Rather, if nonspecific ileitis is identified, and the patient has ulcerative colitis involving the entire colon, the term “UC with backwash ileitis” is more appropriate. Suggested standard descriptions of ileal inflammation are provided in Table 15.4.

Table 15.4

Ileitis—suggested descriptions

1.Normal ileum—an ileum that is both macroscopically and microscopically normal, without features of inflammation. Lymphoid nodularity of the terminal ileal Peyer’s patches should be considered a normal finding |

2.Histologic backwash ileitis (microscopic inflammation of the ileum)—active ileitis (focal or diffuse) with or without features of chronicity identified on histologic examination, with an endoscopically normal ileum |

3.Endoscopic and histologic backwash ileitis—endoscopic erythema and granularity of the terminal ileum, confirmed upon histology with findings of active or chronic ileitis |

4.Crohn disease of the ileum—linear ulceration, cobblestoning, and narrowing of the ileum, often associated with ulceration of the ileocecal valve. These findings may be demonstrated either by endoscopy of the terminal ileum, or by barium upper GI with small bowel follow-through contrast study. The histology may be normal (due to the focal nature of the inflammation), or demonstrate acute and chronic ileitis. The presence of noncaseating granulomas on ileal biopsy automatically classifies a patient as having CD of the ileum |

Gastritis in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease

Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) is increasingly being performed as part of the initial evaluation in children with suspected inflammatory bowel disease, especially if a child is under anesthesia. Performing an EGD in a child adds very little time to the initial diagnostic evaluation, and may identify gastric pathology that requires additional medical treatment (e.g., proton pump inhibitors or immunomodulators). The Porto working group of ESPGHAN has recommended routine upper endoscopy at initial presentation to aid in the diagnosis of pediatric IBD [1]. However, in certain patients, the endoscopic or histologic findings seen on EGD may raise uncertainty as to whether the patient has CD or UC.

It is now well documented that patients with both CD and UC may have upper GI tract inflammation, and that the prevalence of inflammation seen in the esophagus, stomach, and duodenum is comparable in both CD and UC. Both nonspecific gastritis and focally enhanced gastritis (defined as perifoveolar or periglandular mononuclear or neutrophilic infiltrate around gastric crypts) may be identified in the gastric biopsies of patients with IBD. A large epidemiologic study of both adults and children determined that 25% of IBD patients have gastritis, and approximately 13% have duodenitis, with this upper tract inflammation being more common in younger patients [26]. Focal gastritis is more common in the gastric biopsies of patients with Crohn disease than patients with ulcerative colitis [1, 27, 28]. In a retrospective study of 238 children with UGI biopsies, focal gastritis was present in 5/24 (20.8%) of patients with UC, but it was more common in CD patients (28/43 or 65.1%) compared to 2.3% of controls without IBD and one of 39 with Helicobacter pylori [29].

The most useful histologic finding on upper endoscopy in the IBD patient is the identification of granulomas on routine biopsy of the esophagus, stomach, or duodenum. The performance of such biopsies in IBD patients at initial diagnosis will identify non-caseating granulomas in 12–28% of patients, which will establish the formal diagnosis of Crohn disease [27, 30–33]. In one study by Kundhal et al., 39 children with ulcerative or indeterminate colitis and normal barium small bowel radiographs underwent upper endoscopy. Granulomas were present on antral biopsy in five patients (14%), thus changing the diagnosis to CD [31]. In a review of duodenal, antral and esophageal biopsies from children with CD and UC in whom H. pylori infection had been excluded, Tobin noted granulomas in 40% of patients. While the majority of these were identified in the stomach, granulomas could also be identified in the esophagus or duodenum [33]. While granulomas may also be seen in other conditions, including H. pylori disease and sarcoidosis, the identification of upper GI tract granulomas on upper endoscopy strongly suggests Crohn disease in a child with IBD.

Periappendiceal Inflammation in Ulcerative Colitis

The finding of right colonic inflammation in a patient with disease limited to the left colon suggests a skip area, which should suggest Crohn disease. However, patients with UC that does not extend to the cecum may have an inflamed distal (left) colon, a normal transverse and ascending colon, and evidence of periappendiceal and cecal inflammation (a.k.a. a “cecal patch”). The finding of a “cecal patch” was well documented on studies of colectomy specimens, which demonstrate appendiceal involvement as a “skip lesion” that can be seen in UC [34–38]. More recently, prospective and retrospective studies of colonoscopy and histology have confirmed that periappendiceal inflammation is common in UC [38–44]. In a recent large series involving adults and children, 29 of 369 (7.9%) of UC patients (in whom the disease did not involve the entire colon) had evidence of cecal inflammation [45]. In one study examining resected appendices in patients with CD and UC, appendiceal inflammation was noted in both groups, and the inflammation was of comparable severity [46]. In summary, mild periappendiceal inflammation can occur in both CD and UC. In CD, this appendiceal inflammation usually occurs in conjunction with more extensive inflammation of the ileum and cecum, with a more normal distal colon. In contrast, in UC, the appendiceal inflammation is usually seen with pancolitis, but can be seen as an isolated “cecal patch” in patients with left sided UC or proctitis.

Rectal Sparing and Patchiness

The classic definition of ulcerative colitis requires diffuse continuous disease that begins in the rectum and extends proximally, to some point higher up in the colon, without “skip areas.” “Rectal sparing,” where the rectum is not inflamed (absolute rectal sparing), or inflamed less severely than the more proximal colon (relative rectal sparing) was thought to be suggestive of Crohn disease. Recent studies emphasize that colonic inflammation may be less severe in children than in adults with new onset UC, leading to relative or absolute rectal sparing. Three studies have directly compared new onset UC in children to adult-onset UC, and all of these suggested less severe and less diffuse architectural abnormalities in children. Two of these studies demonstrated a higher prevalence of rectal sparing in children compared to adults [47–49].

The term “patchiness” refers areas of normal mucosa (either endoscopically or histologically) between two areas of colonic inflammation. As with rectal sparing, the finding of histologic “patchiness” was originally thought to be suggestive of a Crohn disease skip area. However, a number of studies suggest that rectal sparing and patchiness can be seen in ASLC, new onset untreated ulcerative colitis in children, and medically treated ulcerative colitis in adults [48–51]. In the study by Glickman et al., 16% of children with new onset treatment naïve UC had patchy chronic colitis, compared to no adults. In contrast, patchy disease can be seen in adults at the time of colectomy, and such a finding does not necessarily warrant a change in diagnosis from UC to CD [52]. The precise reason why the histology of new onset UC differs between children and adults remains unclear, though it may be a function of younger age and shorter duration [49].

It is important to emphasize the effects of treatment on a patient with either CD or UC. Certain treatments, particularly immunomodulators and infliximab, are highly effective at inducing mucosal healing. Even milder medical therapies such as aminosalicylates may cause attenuation of inflammation, resulting in patchiness [50, 53]. Therefore, the best opportunity to distinguish CD from UC is at the time of the initial endoscopic evaluation.

Radiographic Imaging Studies in the Differentiation of UC from CD

The role of barium radiography in differentiating between CD and UC is well established, and most of the initial epidemiologic studies that classified these two diseases utilized the findings on barium radiography to assist in the differentiation of these two conditions. In Crohn disease of the ileum, the terminal ileum, ileocecal valve, and cecum demonstrate various degrees of narrowing, ulceration, and stenosis [54]. In contrast, in UC with backwash ileitis the terminal ileum has a granular appearance, the ileocecal valve is wide open, and the cecum is normal caliber. Some authors have questioned the utility of barium radiography in otherwise healthy patients with a normal ileoscopy, it is unclear how often the findings of a barium study change the diagnosis [54].

While at one time, experts recommended that all children with IBD undergo an upper GI with small bowel follow through at the time of initial diagnosis, newer imaging modalities are currently replacing the barium meal at many centers. The expertise and the use of non-barium imaging modalities (ultrasound, nuclear medicine, computed tomography, and MRI studies) in the differentiation of CD from UC vary greatly from center to center. All of these modalities have been utilized in the diagnosis of IBD patients, with good results [19, 55–57]. However, the benefits in diagnosis must be weighed against the study’s cost and the radiation exposure to the patient [58].

The most appealing of these newer modalities is MRI, because MRI generally provides reasonable quality images without exposure to radiation. Of the above modalities, MRI scan of the bowel offers the potential benefit of accurate anatomic localization without radiation. Recent studies suggest that MRI can differentiate between CD of the ileum and backwash ileitis by evaluating bowel wall thickness of the ileum [19, 56]. A prospective study in children comparing MRI to CT scan suggested comparable sensitivity and specificity for detecting small bowel findings such as bowel wall thickening, mesenteric inflammation, fistula, and abscess [59]. However, in this clinician’s experience, MRI is highly operator dependent, and nonspecific abnormalities such as “jejunal enhancement” may mislead the radiologist and clinician. Thus, I recommended not changing a patient’s diagnosis from UC to Crohn disease simply on the basis of a jejunal MRI finding alone. To have pancolonic “UC-like disease” and true jejunal inflammation is extremely rare. If an MRI demonstrates a nonspecific abnormality in the mid small bowel, such a finding should be confirmed by some sort of other modality (either another type of imaging study or enteroscopy).

Serologic and Genetic Testing

A number of serum markers of variable sensitivity and specificity are currently available as a “diagnostic panel for inflammatory bowel disease.” Serology is discussed in greater detail elsewhere in this book (Chap. 18). The utility of serology in differentiating between CD and UC is highly controversial, and there remains doubt if this test has utility in routine clinical pediatric practice [60, 61]. The anti neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (pANCA) is identified in approximately 75% of patients with ulcerative colitis, and up to 20% of patients with Crohn disease [62–64]. In contrast, antibodies to Saccharomyces cerevisiae antibody (ASCA) are present in 40–80% of patients with Crohn disease, are rarely if ever seen in UC, and are preferentially associated with ileocecal Crohn disease.

As previously discussed, the current gold standard for diagnosis of CD and UC is based on endoscopy and histology, not on serology. However, there is increasing evidence, that serologic markers may be predictive of pouch complications, including Crohn disease of the pouch. Coukos et al. identified two markers (ASCA and CBir) as predictive of the risk of pouchitis, pouch fistulae, or need for pouch takedown [65]. In a second study, Melmed et al. identified family history of Crohn disease and positive ASCA serology as risk factors for development of Crohn disease of the pouch [66]. Therefore, while we do not routinely obtain serologic markers in most straightforward cases of IBD, we do consider them in children with severe colitis that may be facing surgery.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree