3 Children’s Voices

The Experience of Patients and Their Siblings

Life is so strange. Sometimes you feel it’s like a book with chapters to fill, never ending.

Sometimes it’s like a chess game where you have to make each move so carefully.

Other times it’s like a mystery where each hidden chamber reveals its secrets.

It is even a war where to live it is to win it.1 (p. 131)

It’s no privilege having someone with cancer in your family. Of all the things I ever could have chosen, having my brother get cancer is not one of them.2 (p. 38)

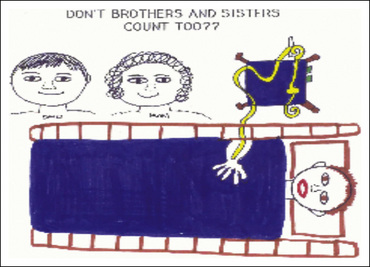

Although the healthy siblings live the illness experience with the same intensity as the patient and parents, historically, they have stood outside the spotlight of attention and care.3–4 Many of these children demonstrate positive growth in their maturity and empathy. Yet their distress can be significant, including elevated rates of anxiety and depression; symptoms of post-traumatic stress; few peer activities; lower cognitive development scores and school difficulties; diminished parental attention and overall ratings of a poor quality of life.5–6 Sibling relationships are a crucial axis within the family system and the children’s mutual caring and devotion can be enhanced rather than overlooked (Figs. 3-1 and 3-2).

Fig. 3-1 Don’t brothers and sisters count too??

(Reprinted from Sourkes B et al. Food, toys, and love: pediatric palliative care, Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care 35(9):345–392, 2005.)

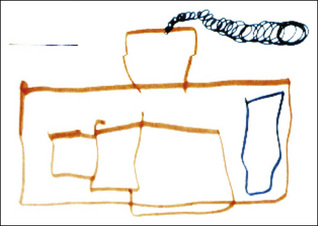

Fig. 3-2 I am crying because I want my brother to be with me.

(Reprinted from Sourkes B et al. Food, toys, and love: pediatric palliative care, Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care 35(9):345–392, 2005.)

A group of siblings were asked: “Imagine that you are doing a campaign on behalf of siblings of seriously ill children. Draw a poster to illustrate your cause.” The children drew an ill child in a hospital bed, surrounded by medical equipment, the parents at bedside. No siblings are present. They entitled their poster:“Don’t brothers and sisters count too??”7

Developmental Considerations

Infants and toddlers (AGES 0-3)

Preschool children (AGES 3-5)

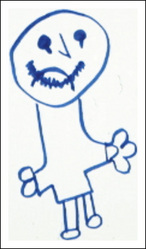

Matthew, 4, who was receiving palliative care for a brain tumor, told the psychologist: “I’m not sick anymore” and adamantly denied any discomfort. His response to most queries by his parents or the medical team was “I’m OK” or “I’m fine” even when it was obvious that he was not. In fact, his non- or underreporting of symptoms made it difficult for his mother to administer pain medication effectively. The psychologist introduced Matthew to a rabbit puppet that he promptly named Donald Bunny. She used the puppet to model the reporting of symptoms (e.g., Donald Bunny has a headache, his eyes hurt when it is too bright, etc.). Matthew watched and listened with some interest. The psychologist left the puppet with him. At the next session, his mother said Matthew had begun reporting symptoms attributed “through the voice” of Donald Bunny. He still would not verbally acknowledge that he had any of these problems; however, his drawing of a dark and threatening “batman tunnel” connoted distress and pain (Fig. 3-3) and contrasted with his earlier bright image (Fig. 3-4). By the next session, while Matthew still would not initially mention any of what had been “bad” during the week, he did allow his mother to list some of his symptoms and would nod affirmatively to them. He then added spontaneously for the first time: “I don’t like when I cough.”8

Fig. 3-3 Batman tunnel.

(Reprinted from Sourkes B: “Psychological impact of life-limiting conditions on the child.” In Goldman, Haines, Liben [eds]. Oxford Textbook of Palliative Care for Children (2006). By permission of Oxford University Press.)

Fig. 3-4 Untitled early image.

(Reprinted from Sourkes B: “Psychological impact of life-limiting conditions on the child.” In Goldman, Haines, Liben [eds]. Oxford Textbook of Palliative Care for Children (2006). By permission of Oxford University Press.)

A 3-year-old sibling manifested intense anxiety both at home and at preschool during his sister’s long hospitalization. He drew a picture of the hospital with the following commentary: “A building with only three windows because some fell out and broke on the street. People have to be careful or their toes could get cut off. Nobody is in the hospital—they were all in a meeting. But you were there and were happy to see us and then everyone else came back. I was born and I got poison ivy and I died in the car. My sister was scared” (Fig. 3-5).

School-age children (AGES 6-12)

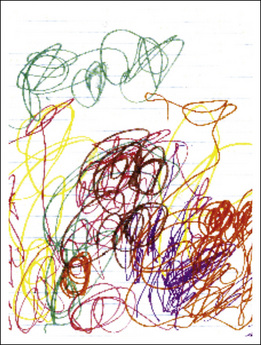

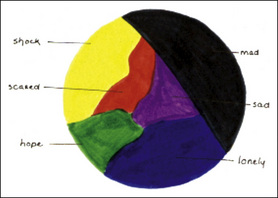

Through a drawing (Fig. 3-6), an 8-year-old boy captured the immediacy of his response to the diagnosis of a life-threatening illness: “When I heard that I had leukemia, I turned pale with shock. That’s why I chose yellow—it’s a pale color. Scared is red—for blood. I was scared of needles, of seeing all the doctors, of what was going to happen to me. I was MAD [black] about a lot of things: staying in the hospital, taking medicines, bone marrows, spinal taps, IVs, being awakened in the middle of the night. I was sad [purple] that I didn’t have my toys and that I was missing out on everything. I chose blue for lonely because I was crying about not being at home and not being able to go outside. Green is for hope: getting better, going home, eating food from home, and seeing my friends.” He has articulated the shock; the fear of everything from the concrete medical procedures to the sudden possibility of an altered future (“what was going to happen to me”); the constellation of sadness, grief, and loneliness of separation; and the absence from his normal life. Accompanying all these feelings is a forthright statement of hope.1(p. 31)

Fig. 3-6 How I felt when I heard that I had leukemia.

(Reprinted and adapted from Armfuls of Time: The Psychological Experience of the Child with a Life-Threatening Illness by Barbara M. Sourkes, 1996, by permission of the University of Pittsburgh Press.)

Siblings also experience a sense of “apartness” of being different or stigmatized, by having a seriously ill brother or sister. These children often live in fear of becoming sick themselves, along with suffering a complicated mix of guilt at having escaped the illness and shame at feeling this relief. They are exceedingly conscious of the physical exigencies of the illness, as well as the impact on the child’s functioning. Private theories about what caused the illness are common, and the siblings frequently implicate themselves in the explanation. They often express a fervent wish to understand and be more involved.3–4

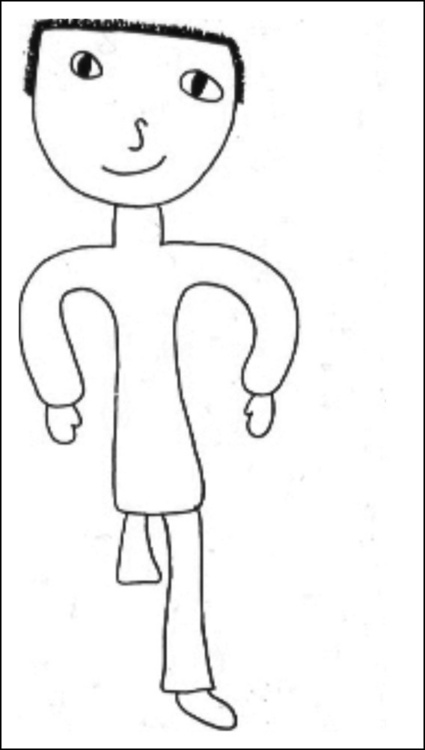

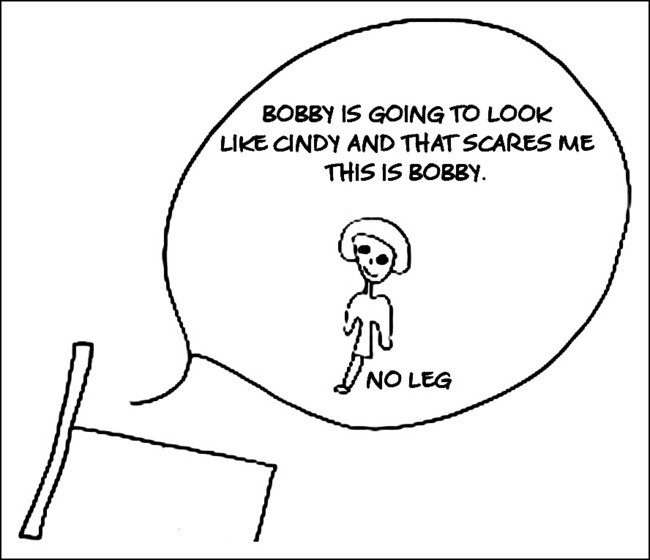

Bobby, 10, reported his version of the sequence of events that led to his sister’s diagnosis of osteosarcoma and amputation: “She hurt her leg on the chain of her bike. She didn’t even notice it until I pointed it out to her. I don’t even ride my bike anymore. One night I went out and broke the chain so I couldn’t ride it. I told my mother it broke by itself, but I broke it.”3 (p. 55) He wrote a story: “This is my sister (drew a one-legged stick figure) and this is me (drew a two-legged stick figure). There is a difference. But I still think that this is the same Cindy and I know that she is not the same to you and I think that she is beautiful.” He then drew a picture of Cindy, stressing her very short hair and her stump. He expressed much concern about how the stump would look.3 (p. 57) (Fig. 3-7) In a subsequent session, Bobby admitted to nightmares of “the same thing” happening to him (Fig. 3-8).

Fig. 3-7 Bobby’s portrait of Cindy.

(Reprinted with permission from Kellerman, J. Psychological Aspects of Childhood Cancer. (1980). Courtesy of Charles C. Thomas, Publisher, Ltd., Springfield, Illinois.)

Fig. 3-8 Bobby’s nightmare.

(Reprinted with permission from Kellerman, J. Psychological Aspects of Childhood Cancer. (1980). Courtesy of Charles C. Thomas, Publisher, Ltd., Springfield, Illinois.)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree