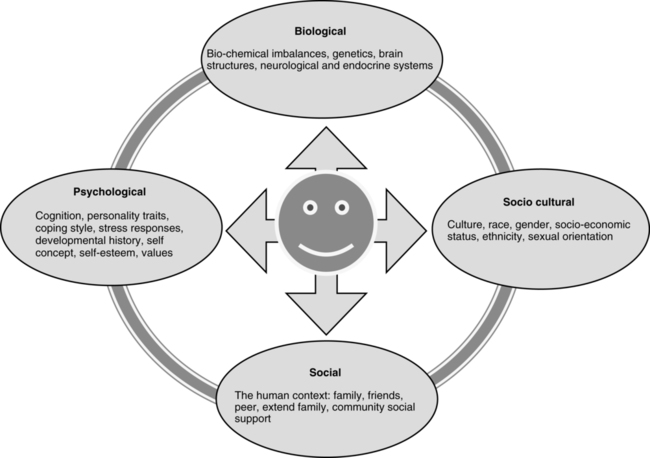

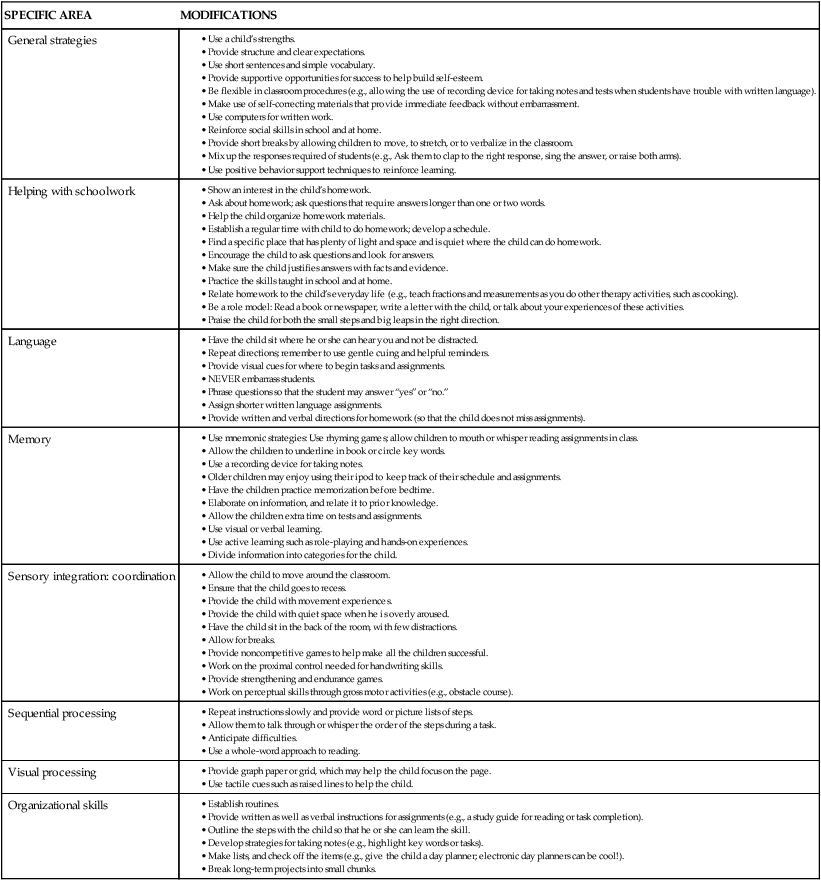

13 KERRYELLEN G. VROMAN and JANE CLIFFORD O’BRIEN After studying this chapter, the reader will be able to accomplish the following: • Define psychosocial occupational therapy practice for children and adolescents. • Recognize the signs of behavioral and mental health disorders seen in children and adolescents. • Recognize the symptoms of behavioral and mental health disorders seen in children and adolescents. • Assist in the occupational therapy evaluation process. • Recognize typical assessments used by the occupational therapy practitioner to develop intervention. • Use evaluation results to guide mental health and psychosocial practice. • Be familiar with types of frames of reference that direct intervention in psychosocial practice. • Select activities that support evidence-based practice. • Be familiar with the types of group intervention for children and adolescents. Occupational therapy (OT) practitioners employed in all pediatric settings (early intervention programs and school systems) provide psychosocial occupational therapy to address children’s mental health, since physical and emotional well-being through successful participation and adaptation is a fundamental goal of therapy. In addition, some children and their families are referred to OT because their mental health disorders interfere with successful occupational performance and participation. The performance problems associated with these disorders include regulating and controlling behaviors, interacting and collaborating with other children, forming and maintaining friendships, relating to and taking directions from adults, and attending to tasks.8 Children diagnosed with mental disorders also present as having difficulties in regulating emotions, organizing thoughts, and demonstrating appropriate behaviors. The overall focus of this chapter is mental health disorders and behavioral problems that present in childhood and adolescence. The descriptions of childhood mental health disorders in this chapter are consistent with the diagnostic criteria of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-VI-TR).5 These diagnostic categories assist health care professionals to describe and organize the physical, mental, and behavioral signs and symptoms to determine the most effective interventions and to measure treatment effectiveness.5 One out of five children has a mental health problem or disorder that is likely to disrupt his or her ability to perform age-related activities. These disorders include major depression, bipolar disorder, anxiety disorders, disruptive behavioral disorders, and schizophrenia (Box 13-1). In adolescence, the risk of mental health disorders increases significantly; eating disorders, aggressive and antisocial behaviors, and substance abuse are more prevalent than they are in younger children.26 Effective treatment for mental health problems in childhood and adolescence is crucial, since mental health disorders and behavioral problems disrupt learning and social development, which, in turn, can have an effect on adult functioning. For example, disorders that develop in adolescence are associated with poorer occupational performance and adaptation in adulthood.27 In children and adolescents, mental health disorders often present as behavioral problems and/or as difficulty performing everyday activities. They are the result of the interaction of biological, behavioral, psychological, and social factors (Figure 13-1). Family history of mental illness, or sexual, physical, or emotional abuse or stresses associated with lower socioeconomic circumstances such as poverty or parental unemployment increase the risk of mental illness (Box 13-2). A biological predisposition or genetic component may make a child vulnerable to a mental health disorder, but a child will only develop a disorder when other factors are also present. Therefore, an integrative model that considers all biological, behavioral, psychological, and sociocultural dimensions is typically used to understand each child’s mental health disorder.33 The biological dimension includes genetics, and the structures and functions of the brain such as the role of neurotransmitters, sensory processing, and the endocrine system. Some disorders have explicit genetic causes that are present at birth. These conditions are often those with multiple symptoms, including intellectual disabilities. Other disorders have genetic or biological origins that are less clearly identified. This includes disorders such as depression, anxiety disorders, and those on the autism spectrum. The psychological dimensions encompass cognitive, emotional, and personality factors, namely, characteristics of personality, learning abilities, emotional arousal, coping abilities, self-concept, and self-esteem. The social dimension includes relationships of family, friends, and other significant adults (such as teachers and extended family), while the sociocultural dimension encompasses such factors as gender orientation (see Chapter 9), ethnicity, culture, religion, and socioeconomic status. Attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is the most common behavioral and cognitive disorder diagnosed in childhood in the United States.7 The three types are: (1) predominantly hyperactive-impulsive type, (2) predominantly inattentive type, and (3) combined type. A diagnosis of ADHD relies on an experienced multidisciplinary health care team to make the determination that the symptoms are interfering with the child’s ability to perform ADLs and that these symptoms are not the result of another medical, psychiatric, or social condition.19 It is necessary to rule out other reasons that children have difficulty paying attention in class, such as anxiety, sensory difficulties, feeling overwhelmed, fatigue, and boredom. Diet, routines at home, and exercise can also influence a child’s ability to pay attention in class. The symptoms must be evident before age 7, last for at least 6 months, and not be associated with an anxiety disorder.19 Interventions for ADD may include medication (stimulants), behavioral modification techniques, sensory modulation, and learning strategies to help these children focus on a task. Children with ADD generally respond to lower levels of medication compared with children with ADD of the hyperactivity type.14 Behavioral strategies can be very beneficial for these children. This may include classroom modification such as low sensory areas, which help children focus on their work and can be calming for a child when overstimulated (Table 13-1). TABLE 13-1 Classroom Modifications to Improve Attention Some children with ADD have excessive energy and motor activity. They are diagnosed with ADD of the predominantly hyperactivity type (referred to as ADHD), which is more common in boys and children from lower socioeconomic backgrounds.15 Signs of ADHD include fidgeting, squirming, talking excessively, and impulsive behavior (e.g., difficulty waiting one’s turn, and interrupting others who are talking). Other features associated with ADHD include sleep disorders, mood fluctuation, emotional hypersensitivity (i.e., emotional lability), poor self-esteem, and low frustration tolerance.27 It is common for children with ADHD to experience difficulties relating to other children. As in the case example of Thomas, a child with ADHD would receive a comprehensive evaluation before a diagnosis. The team of health care and educational personnel determines if there are any other causes for the impulsive-hyperactive behaviors. An OT practitioner observes and evaluates the child in the classroom, at home, and in the clinic and provides information on how the child’s behaviors affect his or her daily functioning, especially during play and learning tasks. The OT practitioner provides strategies and modifications to help the child regulate his or her emotional arousal and manage sensory distractions. Interventions include sensory integration therapy, accommodations and modifications in the classroom and home environment, self-regulation strategies, positive behavioral support, cognitive–behavioral therapy, and monitoring the behavioral outcomes of medication. OT practitioners work with teachers to develop therapy goals for an individualized education program (IEP). Their work with family involves developing parenting strategies to create an environment that supports a child to modify and regulate his or her behavior. The work with families and teachers is likely to involve positive behavior support strategies based on an applied functional behavioral analysis frame of reference (Table 13-2).12 TABLE 13-2 Psychosocial Frames of Reference • Identifying patterns of thinking and core beliefs and being aware of how thinking affects feelings and behavior (e.g., “I always fail”) and leads to anxiety in new situations and not trying new activities because of the fear of failure. • Cognitive restructuring, also called reframing thinking. This involves changing beliefs and thinking patterns. • Self-monitoring and self-talk • Learning skills to reduce stress, such as relaxation • Developing problem-solving skills to address client-identified problems • Homework assignments to consolidate learning and transfer it beyond the therapy setting CBT, cognitive behavioral therapy; OT, occupational therapy. Data compiled from Furr SR: Structuring the group experience: A format for designing psycho-educational groups, J Specialists Group Work 25:29, 2000; Jones KD, Robinson EH: A model for choosing topics and experiences appropriate to group stage, J Specialists Group Work 25:356, 2000; Kramer P, Hinojosa J: Frames of reference for pediatric occupational therapy, ed 2, Baltimore, MD, 1999, Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; Sommers-Flanagan R, Barrett-Hakanson T, Clake C, et al: A psycho-educational school-based coping and social skills group for depressed students, J Specialists Group Work 55:170, 2000; Stein F, Culter SK: Psychosocial occupational therapy: A holistic approach, ed 2, New York, 2002, Delmar; Crone D, Robert Horner R: Building positive behavior support systems in schools, New York, 2003, The Guildford Press. Rodney’s behaviors are characteristic of a conduct disorder, characterized by long-standing behaviors that violate the rights of others and the rules of society. The following behaviors characterize conduct disorder in children and adolescents:5,11 • Physical aggression toward other people or animals • Participation in mugging, purse snatching, shoplifting, or burglary • Destruction of other people’s property (e.g., setting fires) • Breaking of rules (e.g., running away from home or skipping school) • Impaired school performance, especially verbal and reading skills Children with conduct disorder are at high risk of poor outcomes, including dropping out of school, unemployment, and engaging in criminal behaviors and substance abuse. If left untreated, many will develop antisocial personality disorder as adults (i.e., in approximately 40% of cases, childhood-onset conduct disorder develops into antisocial personality disorder).29 Antisocial personality disorders are associated with serious crimes, including rape, physical assault, and homicide.5 The primary symptoms of oppositional defiant disorder (ODD) are negative, hostile, and defiant behaviors that are uncharacteristic of typical children.5 Children and early adolescents with ODD display outbursts of temper, argue, defy adults, and are especially hostile to authority figures. These children seem to be angry all the time and resent rules; they become easily annoyed and readily blame others for their mistakes. Behaviors that might be observed are frequent temper tantrums; mean, hateful talking; revenge-seeking behaviors; and deliberately annoying others. These behaviors differ in duration and intensity from the occasional “difficult” periods some children and adolescents may experience.5 The ongoing oppositional behavior and stormy relationships with teachers and other children result in poor academic performance in school and few friendships.10 Children with ODD may eventually grow out of it, especially if the onset occurs in preschool years. Adolescents diagnosed with ODD are more likely (75%) to have symptoms that persist into adulthood.2

Childhood and adolescent psychosocial and mental health disorders

Understanding mental health disorders

Disruptive behavior disorders

Attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder

Predominantly hyperactivity: impulsive type

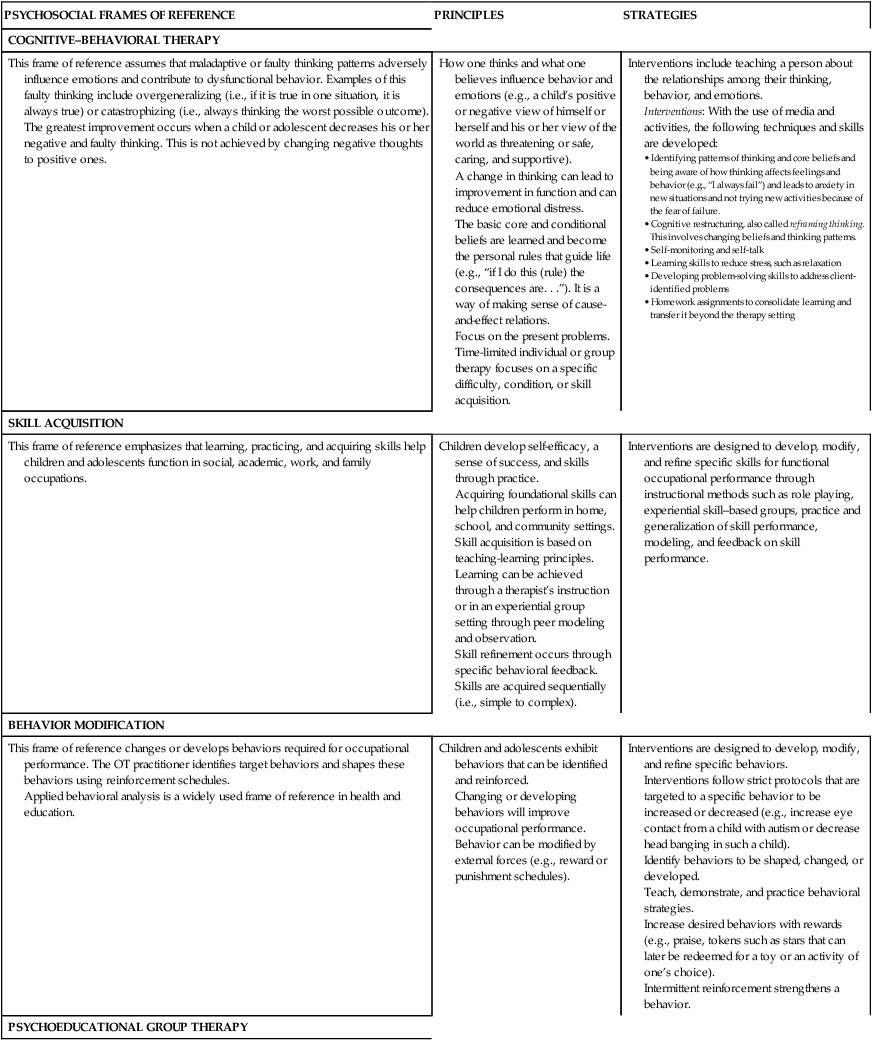

PSYCHOSOCIAL FRAMES OF REFERENCE

PRINCIPLES

STRATEGIES

COGNITIVE–BEHAVIORAL THERAPY

This frame of reference assumes that maladaptive or faulty thinking patterns adversely influence emotions and contribute to dysfunctional behavior. Examples of this faulty thinking include overgeneralizing (i.e., if it is true in one situation, it is always true) or catastrophizing (i.e., always thinking the worst possible outcome). The greatest improvement occurs when a child or adolescent decreases his or her negative and faulty thinking. This is not achieved by changing negative thoughts to positive ones.

How one thinks and what one believes influence behavior and emotions (e.g., a child’s positive or negative view of himself or herself and his or her view of the world as threatening or safe, caring, and supportive).

A change in thinking can lead to improvement in function and can reduce emotional distress.

The basic core and conditional beliefs are learned and become the personal rules that guide life (e.g., “if I do this (rule) the consequences are. . .”). It is a way of making sense of cause-and-effect relations.

Focus on the present problems.

Time-limited individual or group therapy focuses on a specific difficulty, condition, or skill acquisition.

Interventions include teaching a person about the relationships among their thinking, behavior, and emotions.

Interventions: With the use of media and activities, the following techniques and skills are developed:

SKILL ACQUISITION

This frame of reference emphasizes that learning, practicing, and acquiring skills help children and adolescents function in social, academic, work, and family occupations.

Children develop self-efficacy, a sense of success, and skills through practice.

Acquiring foundational skills can help children perform in home, school, and community settings.

Skill acquisition is based on teaching-learning principles.

Learning can be achieved through a therapist’s instruction or in an experiential group setting through peer modeling and observation.

Skill refinement occurs through specific behavioral feedback.

Skills are acquired sequentially (i.e., simple to complex).

Interventions are designed to develop, modify, and refine specific skills for functional occupational performance through instructional methods such as role playing, experiential skill–based groups, practice and generalization of skill performance, modeling, and feedback on skill performance.

BEHAVIOR MODIFICATION

This frame of reference changes or develops behaviors required for occupational performance. The OT practitioner identifies target behaviors and shapes these behaviors using reinforcement schedules.

Applied behavioral analysis is a widely used frame of reference in health and education.

Children and adolescents exhibit behaviors that can be identified and reinforced.

Changing or developing behaviors will improve occupational performance.

Behavior can be modified by external forces (e.g., reward or punishment schedules).

Interventions are designed to develop, modify, and refine specific behaviors.

Interventions follow strict protocols that are targeted to a specific behavior to be increased or decreased (e.g., increase eye contact from a child with autism or decrease head banging in such a child).

Identify behaviors to be shaped, changed, or developed.

Teach, demonstrate, and practice behavioral strategies.

Increase desired behaviors with rewards (e.g., praise, tokens such as stars that can later be redeemed for a toy or an activity of one’s choice).

Intermittent reinforcement strengthens a behavior.

PSYCHOEDUCATIONAL GROUP THERAPY

The purpose of the psychoeducational group is to share information along a common focus and learn from the experiences and knowledge of group members. This process facilitates change and/or the development of skills.

This approach is often used in school-based programs to develop or improve social, communication, or coping skills.

Through knowledge comes change.

To develop knowledge and skills for coping with crisis events, developmental transitions, mental health disorders, or current situational challenges (e.g., parental divorce, adolescent difficulties, depression, or bullying)

Draws from cognitive–behavioral principles

Education is a significant component.

Focuses on the here and now

Intentional use of group experience for mutual and vicarious (by the examples of others and observation) learning as well as support.

Time-limited and theme-focused groups of children and adolescents with similar needs or difficulties.

A well-developed curriculum with sequential instructional sessions in which a variety of teaching methods are used, such as videos, handouts, PowerPoint presentations, and blackboards. Interactive and experiential learning strategies are important components.

The techniques consist of brief lectures or presentations, small-group discussions, written exercises, role playing and behavior rehearsal, peer group modeling and learning from others, and homework tasks to reinforce learning and transfer it to everyday settings.

APPLIED BEHAVIORAL ANALYSIS

Positive Support Behavior: This approach consists of systemic and individualized strategies for achieving social and learning outcomes.

The goal is preventing problem behavior.12

All behavior has a purpose for a child, and behavior is related to context.

Challenging behaviors are symptoms.

Interventions respect the child’s preferences, dignity, and goals.

Relationships are the building blocks of prosocial behaviors

Learning new skills takes time.

Teach skills directly.

Ask why a child is acting the way he or she is acting, as there is always a reason.

Identify patterns of behavior; if problems are predicted, they can be prevented.

A-B-C Model: Identify the Antecedent behavior or event that precedes the child’s behavior. Identify the Behavior that is to be acquired or decreased, and establish Consequences and teach skills.

COACHING MODEL

The premise is that children will be more successful at reaching the goals that they develop themselves. Children will learn life-long strategies through setting goals and take progressive steps toward meeting goals successfully. This child-directed model requires that the OT practitioner provide direction, support, advice, and strategies. This takes the form of coaching and mentoring.

Children and adolescents will be more successful meeting goals that they develop.

Children will develop life-long strategies as they learn to analyze the steps toward goals.

Providing children with support and encouraging them will facilitate progress toward goals.

Children may need “coach” support or mentorship to develop abilities to meet goals.

Teach children to self-evaluate and problem-solve.

Children develop goals with support from OT practitioners.

Analyze the steps to meet goals.

Children set realistic tasks to meet goals.

Support children in addressing steps and learning skills to meet goals.

Get children to practice skills.

Use cueing and reminders.

Act as the children’s “coach” or “mentor” with weekly or daily “check-ins.”

Conduct disorder: childhood onset

Oppositional defiant disorder

Learning disorders

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Childhood and adolescent psychosocial and mental health disorders

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue