1.2 Child health in a global context

Introduction

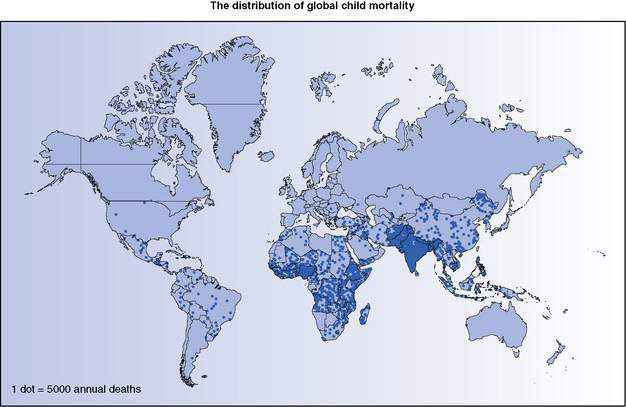

The World Health Organization (WHO) estimated in 2000 that 10.7 million children under the age of 5 years die annually and 99% of these deaths occur in developing countries. By 2008, the estimated number of deaths had fallen to 8.8 million. Figure 1.2.1 shows the distribution of child mortality globally, the majority of under-5 deaths being concentrated in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia. In 2010, it is estimated that 26 countries had child mortality rates greater than 100 per 1000 live births, all in sub-Saharan Africa except two, Afghanistan and Haiti. A further 30 countries had under-5 mortality rates above 50 per 1000 live births.

Causes of global child mortality

The major causes of death in children aged under 5 years globally are listed in Table 1.2.1. The percentages vary widely across regions, with skewed distribution in the Africa region. For example, 94% and 89% of the world’s malaria and HIV/AIDS deaths occur in Africa.

Table 1.2.1 Major causes of death in children under 5 years of age globally, with estimates for 2000–2003 and 2008

| No. of deaths, in thousands | ||

|---|---|---|

| 2000–2003 | 2008 | |

| Deaths in children aged 1 month to 5 years | 6685 (63%) | 5220 (59%) |

| Acute respiratory infections | 2027 (19%) | 1189 (14%)* |

| Diarrhoeal diseases | 1762 (17%) | 1257 (14%) |

| Malaria | 853 (8%) | 732 (8%) |

| Measles | 395 (4%) | 118 (1%) |

| HIV/AIDS | 321 (3%) | 201 (2%) |

| Injuries | 305 (3%) | 279 (3%) |

| Meningitis | 164 (2%) | |

| Pertussis | 195 (2%) | |

| Congenital anomalies | 104 (1%) | |

| Other | 1022 (10%) | 981 (11%) |

| Neonatal deaths | 3910 (37%) | 3573 (41%) |

| Pre-term birth | 1083 (10%) | 1033 (12%) |

| Severe infection | 1016 (10%) | |

| Sepsis | 521 (6%) | |

| Pneumonia | 386 (4%) | |

| Birth asphyxia | 894 (8%) | 814 (9%) |

| Congenital anomalies | 294 (3%) | 272 (3%) |

| Neonatal tetanus | 257 (2%) | 59 (1%) |

| Diarrhoeal diseases | 108 (1%) | 79 (1%) |

| Other | 258 (2%) | 409 (5%) |

| Total deaths in children under 5 years | 10 595 (100%) | 8793 (100%) |

Values in parentheses are percentages of total annual global deaths.

* The apparent dramatic reduction in pneumonia deaths in 2008 compared with 2000–2003 was highly dependent on data from China, the validity of which is uncertain. Note also that deaths from pertussis and meningitis were reported separately in 2008, and neonatal pneumonia was not specifically reported in 2000–2003 data.

Data from: World Health Organization 2005 The World Health Report 2005 – make every mother and child count. WHO, Geneva, p 190 (http://www.who.int/whr/2005/en/) and Black RE, Cousens S, Johnson HL et al. 2010 Global, regional, and national causes of child mortality in 2008: a systematic analysis. Lancet 375:1969–1987.

More than one-third of children who die in developing countries have moderate or severe malnutrition, and malnutrition is implicated in deaths from diarrhoea (61%), malaria (57%), pneumonia (52%) and measles (45%). However, malnutrition is often under-reported in national statistics and under-recognized in clinical settings where childhood malnutrition is so common as almost to be the norm. The situation is even more complex than Table 1.2.1 suggests: although children often present with a single condition (e.g. acute respiratory infection), those who are most likely to die will often have experienced several other infections in recent months, have more than one infection concurrently (e.g. pneumonia and diarrhoea, or pneumonia and malaria) and have malnutrition with micronutrient (such as iron, zinc or vitamin A) deficiency.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree