1.1 Child health and disease

What do we know about children and young people in Australia today?

• 19.4% of the Australian population is now aged 0–14 years (4.1 million children), compared with over 28% in 1971, although children in the Northern Territory comprise about 25% of the population.

• 4.8% of Australian children are Indigenous and 38% of the Indigenous population is aged less than 14 years. This reflects the higher birth rate amongst Indigenous women (2.1 births per 1000 compared with 1.8 per 1000 in the total population) and the younger age structure of the Indigenous population due to shorter life expectancy.

• 5.9% of Australian children were born overseas in 2009 and 33% have at least one overseas-born parent. Sudan-born had the highest proportion (21%) of residents aged 0–14 years, followed by the USA (16%), Afghanistan (14%), South Africa, Singapore, Pakistan and Zimbabwe (12–13% each). Most migrants enjoy health that is equal to or better than that of the Australian-born population, often with lower rates of death, mental illness and disease risk factors.

What are the circumstances of Australian households?

Family income and work

• In 1999, 12% of Australian children aged 0–17 years lived in households with equivalent income of less than 50% of the median household income (relative poverty).

• In 2005–2006, low-income households (those in the second and third income deciles) with children aged 0–12 years accounted for 421 300 households Australia-wide and received on average $347 a week ($218 a week less than median-income households with children aged 0–12 years).

• Jobless families are disproportionately likely to be reliant on welfare, to have low incomes and to experience financial stress. In 2006, 15% of Australian children aged 0–14 years lived in jobless families, a decline from 19% in 1996.

• Nearly half (42%) of Indigenous children aged 0–14 years live in jobless families, three times the proportion of all children. The higher proportion of Indigenous children living in one-parent families contributes to this higher rate, as 45% of Indigenous children live in one-parent families compared with 20% of all children. 68% of Indigenous children living in one-parent families do not live with an employed parent.

• Australia had the second highest proportion of working-age, jobless families with children aged 0–17 years of 24 OECD countries in 2000, largely due to the relatively high rate of one-parent households in Australia and the high rate of joblessness (51%) among this group.

Childcare and early childhood education

Why is the proportion of children in the population declining and what does that mean for children of the future?

Child health

How do we describe child health?

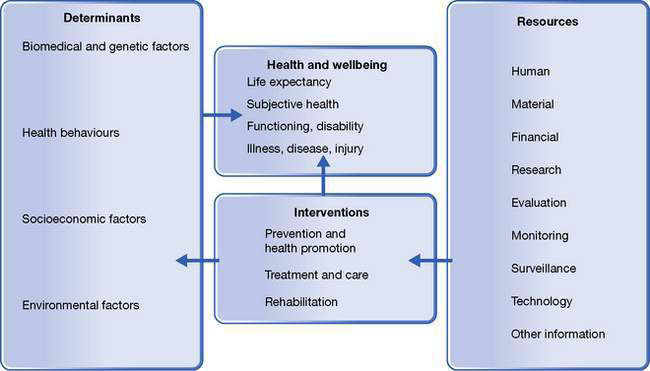

We use rates of mortality and morbidity to evaluate the health status of a community. Mortality is a very crude index of health and is of limited value in assessing the health status and health needs of a community. Morbidity is a measure of the presence or absence of medical diseases or conditions. A widely accepted view is that to describe health adequately involves also measuring a broad range of social and economic risk and protective factors. In 1946, the World Health Organization (WHO) defined health holistically as ‘a state of complete physical, mental, and social wellbeing and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity’. A child’s physical, mental and social wellbeing is inextricably linked to the environment and social values surrounding that child. Furthermore, children and adolescents are growing and developing rapidly, and may be more susceptible than adults to adverse environmental influences (Fig. 1.1.1).

Individual and social determinants of health

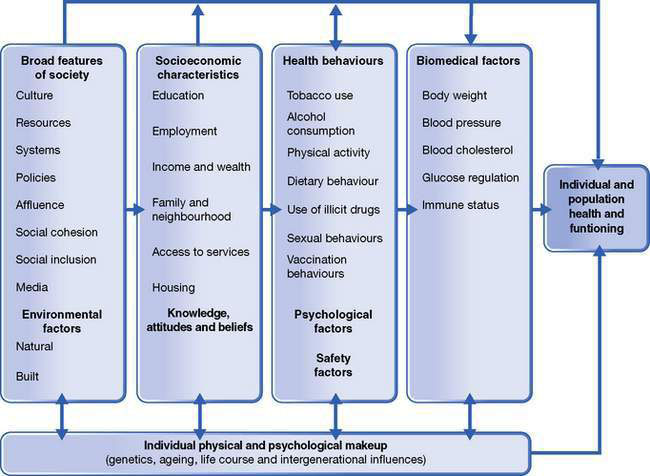

Protective factors promote positive health and development and include factors such as infant breastfeeding, physical activity and sound nutrition. Factors that increase the risk of ill-health in children include overweight and obesity, exposure to tobacco smoke or alcohol use in pregnancy. From a practical point of view, complete paediatric clinical assessment requires a consideration of all aspects of the child’s life, such as the home circumstances, the access to health care, the physical and mental health of the parents, and the quality of community support available. This applies equally to every child whether they present with leukaemia, cystic fibrosis, acute bacterial meningitis, developmental delay, child maltreatment, behaviour problems or even a well-child review (Fig. 1.1.2).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree