Neurological problem

Passing objects hand to hand

8 months

Musculoskeletal problem

Neurological problem

Neurological problem

Co-ordination problem

Gross motor problem

Neurological problem

‘Bottom shuffler’

Musculoskeletal problemm

Neurological problemm

Lack of stimulus

Motor disorderm

Austistic spectrum disorderm

Lack of stimulus

Musculoskeletal problem

Co-ordination problems

In order to be able to identify what is abnormal, you need to have an idea of what a normal child of that age can do. Below are descriptions of what children can normally do at certain ages.

Six weeks

By 6 weeks babies start to gain some control over their head movements and should be able to move their heads from side to side when lying on their fronts. Newborn babies have very blurry vision and cannot ‘fix’ on objects with their eyes but by 6 weeks their vision will have developed enough to allow them to ‘fix and follow’, i.e. focus on an object placed in the centre of their vision and turn their head to the left or right to follow the object with their gaze as it moves. Babies are particularly interested in faces and will be more likely to focus on a face than any other object.

Top Tip

Top TipFrom 6 weeks of age babies start to learn to smile. Don’t expect to always be able to elicit this on examination – ask the parents if baby has been smiling in response to them.

Six to eight months

By 6 months most babies will be able to sit up. They may still be needing support to sit initially but by 8 months most will sit unsupported. They should be reaching out for and grabbing at objects with the palm of their hand and able to hold simple objects; they will also be developing the ability to transfer objects from hand to hand.

By this age babies should be making babbling noises and turning their head to noises out of sight. From 6 months, babies start learning how to feed themselves by picking up food with their hands and start to put everything they pick up in their mouths.

Twelve months

By the time babies reach one year old, they should be able to pull themselves to a standing position and start ‘cruising’ around the furniture (travelling around the room on their feet by grabbing onto furniture with their hands to help them balance). Some children will even be able to walk unsupported by this age (albeit rather unsteadily). They will use a pincer grip (between thumb and fingers) to pick up objects, will be able to wave bye-bye and play peek-a-boo. They will probably be able to say one or two words and understand their name.

Eighteen months

At 18 months old, children should be able to walk independently and may be able to start running a little too. They can hold a crayon to draw random scribbles and build a small tower of bricks (2–4 cubes). They may be starting to use one hand in preference to the other but if this has occurred any earlier than 18 months, this is a worrying sign as it may represent a problem with the side they are not using. They will be able to use between six and 12 words and will be able to use a spoon to feed themselves. At this age children also start to use ‘symbolic play’, e.g. pretending to cook.

Two years

By the time children are 2 years old they are much more steady on their feet and should be able to run around and may be able to kick a ball and jump. They will be able to say more words and will start joining two or three words together to express what they want, e.g. ‘give me teddy’. Most will know five or six body parts, which can be helpful when trying to examine them (‘where is your tummy?’) and will be able to remove items of clothing. At this age they may start with potty training and be dry by day.

Three years

By 3 years of age children can handle three wheels – they will be able to ride a tricycle. Most children at this age can walk up and down stairs (but will probably still have to use two feet on each step on the way back down). Most can draw a circle and build a tower of nine bricks or a little bridge out of three blocks.

Many 3 year olds will chat almost constantly to their parents in three- or four-word sentences and ask a lot of questions. They are able to play with other children and start to understand the concept of taking turns. Most will be fairly independent with toileting, but they won’t be able to wipe themselves effectively at this age.

Top Tip

Top TipIt goes without saying that children continue to develop after the age of 3 but the obvious big milestones (in terms of motor and language skills) mostly happen within those first few years when skills develop very rapidly. After this it becomes a case of refining the skills that they have learnt.

School

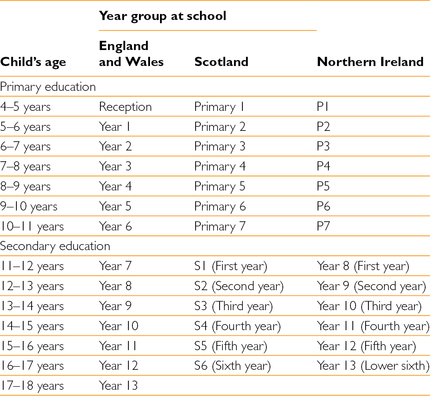

School plays a crucial role in a child’s development and is a big part of their life, so knowing which year group a child belongs to at which age can be helpful in discussions with children and parents. In the UK school starts and finishes at slightly different ages between the different countries, as does progression between ‘primary’ and ‘secondary’ education (in some areas children go to ‘middle school’ between primary and secondary). It may be worth finding out what is the case in your local area as education systems and rules can change. Table 2.2 provides a rough cheat sheet to give you an idea.

Developmental delay and children with disabilities

A child’s development can be delayed in relation to one specific skill or across all developmental aspects (global delay). GLOBAL DEVELOPMENTAL DELAY usually becomes apparent within the first 2 years of a child’s life. It is often associated with a degree of cognitive IMPAIRMENT but this may only become apparent in later years.

Table 2.2 Age ranges of primary and secondary school years in England and Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland.

Many children with DEVELOPMENTAL DELAY will have an underlying medical condition and referral for detailed assessment early on is crucial. Diagnosis can allow treatment to start for the child and genetic counselling for parents if an inherited illness is diagnosed.

In 2007 the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) published Promoting the Rights of Children with Disabilities (Innocenti Research Centre 2007). It opens with this paragraph:

‘Children with disabilities and their families constantly experience barriers to the enjoyment of their basic human rights and to their inclusion in society. Their abilities are overlooked, their capacities are underestimated and their needs are given low priority. Yet, the barriers they face are more frequently as a result of the environment in which they live than as a result of their impairment.’ (Reproduced by permission of UNICEF – Office of Research)

Top Tip

Top TipSo how can you make sure that you don’t become another barrier along the way? Here are some suggestions.

Avoid making assumptions about what a child is or is not able to do.

Avoid making assumptions about what a child is or is not able to do.

Talk to the child too. Just as you would with any other child, don’t just ignore them and talk to the parents. Help them find ways to communicate with you if possible.

Talk to the child too. Just as you would with any other child, don’t just ignore them and talk to the parents. Help them find ways to communicate with you if possible.

They are the experts. Parents of children with long-term conditions often become experts on their child’s health problems and it is vital that they are treated as such. For tips on how to communicate well with expert parents, see Chapter 3 – Communication with Children and Their Parents.

They are the experts. Parents of children with long-term conditions often become experts on their child’s health problems and it is vital that they are treated as such. For tips on how to communicate well with expert parents, see Chapter 3 – Communication with Children and Their Parents.

Be patient. It is incredibly hard work looking after a child who is profoundly disabled, particularly for parents who have other children to look after as well. Be patient, even (and especially) if they are rude to you; they may be reaching the end of their tether. Contact a Family is a national UK charity with a great website to refer parents to if they don’t know of it already (www.cafamily.org.uk). The charity has a freephone national helpline and a website with lots of information on medical conditions and can point parents towards where they can access support in their local area. It is also worth having a look yourself at the information for professionals available on the website.

Be patient. It is incredibly hard work looking after a child who is profoundly disabled, particularly for parents who have other children to look after as well. Be patient, even (and especially) if they are rude to you; they may be reaching the end of their tether. Contact a Family is a national UK charity with a great website to refer parents to if they don’t know of it already (www.cafamily.org.uk). The charity has a freephone national helpline and a website with lots of information on medical conditions and can point parents towards where they can access support in their local area. It is also worth having a look yourself at the information for professionals available on the website.

Be sensitive. A child may have DEVELOPMENTAL DELAY as a result of an illness or injury and have been developing normally before that. Be sensitive when talking to parents about this – they may have had to repeat the story hundreds of times to different health professionals each time their child needs medical attention and it can be stressful and painful recalling what happened.

Be sensitive. A child may have DEVELOPMENTAL DELAY as a result of an illness or injury and have been developing normally before that. Be sensitive when talking to parents about this – they may have had to repeat the story hundreds of times to different health professionals each time their child needs medical attention and it can be stressful and painful recalling what happened.

Do your homework. This child may be very well known to your hospital from multiple previous attendances. Rather than making parents go through all of it again, try having a look at a recent clinic or discharge letter which summarises the child’s past medical history and ongoing medical problems. If you feel that you need to clarify with the parents, you could always show them a copy and ask if everything is up to date and if they want to add anything. Even if the child hasn’t been seen at your hospital before, it is worth asking the parents if they have a summary of their child’s illnesses and medications with them (many will have an organised and printed list with them detailing everything you need to know).

Do your homework. This child may be very well known to your hospital from multiple previous attendances. Rather than making parents go through all of it again, try having a look at a recent clinic or discharge letter which summarises the child’s past medical history and ongoing medical problems. If you feel that you need to clarify with the parents, you could always show them a copy and ask if everything is up to date and if they want to add anything. Even if the child hasn’t been seen at your hospital before, it is worth asking the parents if they have a summary of their child’s illnesses and medications with them (many will have an organised and printed list with them detailing everything you need to know).

Be alert. Children with disabilities are much more prone to abuse – be alert to signs that their parents are not coping, for physical signs on examination of the child or for a change in the child’s behaviour from their normal selves. For more information, see Chapter 4 – Child Protection and Safeguarding.

Be alert. Children with disabilities are much more prone to abuse – be alert to signs that their parents are not coping, for physical signs on examination of the child or for a change in the child’s behaviour from their normal selves. For more information, see Chapter 4 – Child Protection and Safeguarding.

Support for children with disabilities and their families

Children with disabilities can have complex needs, both health and otherwise. This means that lots of different organisations are involved in supporting them (health, education, social services and voluntary services) and making sure that they communicate effectively with one another is difficult. This can be a source of enormous frustration for families when it doesn’t work well.

Child development team

Child development services aim to have lots of different professionals under one roof to try to help communication between them and also to make services easier for families to access. A child development team normally consists of the following people: community paediatrician, speech and language therapist, occupational therapist, physiotherapist, psychologist, special needs teacher, health visitor and social worker. For more information about what each of these people does as part of their job, see Chapter 1 – Getting Started. The main aims of the child development team are to provide a diagnosis, medical management and refer for genetic counselling if appropriate. Many child development teams will only see children with complex needs who require access to more than one of their services.

Social services

All children with disabilities are considered to be ‘CHILDREN IN NEED’ and therefore must be assessed by social services in order to establish what extra support they may need. Social services must keep a register of children with disabilities and help to ensure that services for the child are well co-ordinated.

Education

Children with disabilities must be offered the opportunity to attend mainstream school and the school is legally obliged to make ‘reasonable adjustments’ in order to support the child in doing so if this is what the family wishes. This can vary from making physical adjustments to ensure that a child in a wheelchair can get to lessons to providing one-to-one support in the classroom and at break times.

Some families prefer their child to attend a special school where all the members of staff have expertise and class sizes are much smaller.

There is debate about whether mainstream schooling or special schools are better for children with disabilities. It is vital to listen to the wishes of the child and their parents when considering what will work best in each case.

If a child has complex or severe difficulties then the local education authority is legally obliged to perform an assessment for that child in order to establish what the child’s educational needs are and what support they require. The authority will produce a document called a STATEMENT OF SPECIAL EDUCATIONAL NEEDS which is reviewed annually.

Finances

Caring for a child with disabilities is expensive for a whole host of different reasons. Parents may have reduced income from reducing hours or giving up work completely to look after the child and at the same time have increased costs of multiple trips to the hospital, specialist equipment and sometimes even needing to move to a bigger house in order to accommodate all the new equipment.

There are many different types of financial support available from the state to help cover some of these costs. Contact a Family has helpful information on its website about the different kinds of benefits available as does the UK government website (www.gov.uk) in its ‘help if you have a disabled child’ guide. The Family Fund (www.familyfund.org.uk) provides special grants for children with disabilities in the UK for one-off costs.

There are also many voluntary organisations who may be able to provide support by giving families specialist equipment or advice about what they are entitled to access from the state. The Disabled Living Foundation’s website (www.livingmadeeasy.org.uk/children) has information about what funding is available for buying children’s equipment (from the state and the charity sector).

Transition

Transition to adult services is difficult and needs to be planned carefully. Transfer of information to adult services is crucial to avoid patients being investigated all over again for the same condition. People with learning difficulties are considered children until the age of 21 and once within adult services, there may well be a named learning disabilities specialist nurse who can offer support.

Growth

Keeping a record of how a child is growing is a crucial indicator for their underlying health. This means that measuring head circumference, length and weight (for babies) and weight and height (once over 2 years of age and able to stand) should be a routine part of any examination of a child and you should get into the habit of plotting these numbers on a growth chart.

It is important to know how to measure these things properly and also how to plot them on the growth charts. There are special growth charts available for children with certain conditions (such as Down and Turner syndrome) as they will be expected to grow at a different rate from other children. There are also charts available for Body Mass Index (more about this in the obesity section later in this chapter). See Box 2.1 for details of how to use growth charts properly.

Isolated measurements are less important than the trend of growth a child is showing. Children with normal growth should follow a centile line when you plot their growth (until they reach puberty when growth accelerates). For example, if a child has been following the 50th centile for weight and then the latest value plots them on the 25th, you may not be initially concerned but plan to reweigh them in a few months’ time. If their subsequent weight is below the 25th centile then this might be more of a cause for concern as the trend is continuing downwards. If a child’s height or weight drops by two or more CENTILES then you certainly need to be discussing this with someone senior.