3.11 Care of the adolescent

Adolescent development

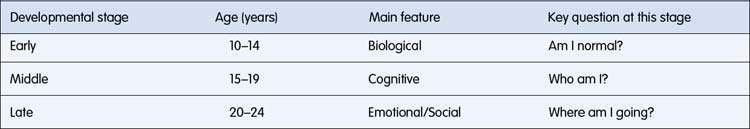

These stages are listed in Table 3.11.1 with an approximate age at which each stage occurs, the main feature of each stage and a key developmental question for young people at this stage.

Burden of illness in adolescence

Some of the major health issues affecting young people in Australia are summarized in Table 3.11.2. The data refer to 12–24-year-old Australians unless stated otherwise.

Table 3.11.2 Some of the key health issues and selected risk factors affecting young Australians

| Health issue | Burden of illness |

|---|---|

| Emotional distress | 9% of 16–24-year-old Australians had high or very high levels of psychological distress in 2007, and 1 in 4 experienced a mental disorder |

| Obesity and overweight | 35% of young Australians were estimated to be overweight or obese (23% overweight but not obese; 12% obese in 2007–2008) |

| Risky substance use | 11% of young Australians were daily smokers, 30% drank alcohol at risky or high-risk levels for short-term and 12% for long-term harm, and 1 in 5 had used an illicit substance in 2007 |

| Chlamydia notifications | Over the past decade, there has been a large increase in notifications for sexually transmitted infections, particularly chlamydia (5-fold increase) |

| Sexual intercourse in year 10 and 12 students | 27% of year 10 students and 56% of year 12 students had experienced sexual intercourse. Two-thirds of sexually active students (68%) used a condom at their most recent sexual encounter |

| Violence | 7% of young adults were victims of physical or sexual assault and almost half were victims of alcohol- or drug-related violence in 2007 |

| Chronic health condition | 60% of young Australians have a long-term health condition in 2007–2008. The prevalence of long-term conditions has declined since 2001 among 15–24 years from 71% to 64%. |

| Disability | 11% of 12–24-year-old Australians had a disability with specific limitations or restrictions; a quarter of these had profound or severe core activity limitations (2008) |

| Abuse and neglect | 4 in every 1000 young people aged 12–17 years were the subject of a substantiated report of abuse or neglect in 2008–2009. Indigenous young people were over-represented at 5 times the rate of other young people |

| Parent health | 16% of parents living with young people rated their health as fair or poor, and around one-fifth had poor mental health. An estimated 16% of young people lived with a parent with disability |

Source: Australian Institute of Health and Wellbeing (AIHW) 2011 Young Australians: their health and wellbeing 2011. Cat. no. PHE 140. AIHW, Canberra.

Risk and protective factors

Many adolescent health problems are a consequence of health risk behaviours (see Table 3.11.2) and developmental challenges. As a consequence, knowledge and assessment of adolescent development, including exposure to risk and protective behaviours, is the foundation of the clinical approach to working with teenagers. Health problems in adolescents don’t occur in isolation; one identified health problem raises the likelihood that there will be other health risk behaviours and various family, peer and community antecedents. Some behavioural concerns in teenagers have their onset in childhood, but others have their onset in adolescence. Once established, there is a greater risk of these behaviours continuing into adult life where they contribute to the adult burden of illness. Early identification and intervention is a desired outcome of any contact by adolescents with the health-care system.

Teenagers, adolescents, youth and young people

• Most teenagers are healthy and happy.

• Like younger children, adolescents continue to develop physically, emotionally and cognitively. All consultations with young people should involve an assessment of adolescent development.

• As children mature through adolescence, they are exposed to greater health risks from involvement in behaviours with significant health consequences, such as drugs and alcohol and sexual intercourse.

• The burden of illness in youth differs from younger children and from adults, being disproportionately affected by mental health problems, the consequences of drug and alcohol use, accidents and self-harm, and complications of sexual activity.

• Healthy adolescent development results from complex interactions between risk and protective factors within the individual, family, peers, school and community.