chapter 10 Cardiovascular Assessment of Infants and Children

Classification of Heart Disease in Children

History of Present Illness and Cardiac Functional Inquiry in the Infant and Young Child

Congenital heart lesions can be divided into three groups:

Age of onset

Significance of the Age of Onset of Congestive Heart Failure

The clinical significance of the age of onset of congestive heart failure is as follows:

Approach to Cardiovascular Examination of the Infant

Because infants and children have an unfortunate habit of not always cooperating, you need to have an organized approach to the cardiovascular examination, while also staying flexible. Do what can be done when the opportunity arises. Begin by assessing the child’s physical development and looking for dysmorphic features, using a systematic approach (see Chapter 5).

Looking for central cyanosis

Because the most pressing clinical problems are congestive heart failure and cyanosis, decide early in the examination whether central cyanosis is present. Because this determination is not always easy, you may find an experienced nurse’s opinion invaluable. Many normal newborns have a deep plethoric appearance as a result of a transiently high hemoglobin concentration, particularly if there was a delay in clamping the umbilical cord. Plethora is not as obvious in the mucous membranes, so look carefully in the baby’s mouth. Deep pressure on the skin may help, because the blanched area does not pink up as quickly in infants with central cyanosis. Many normal infants exhibit a generalized mottling, particularly after being bathed (see Fig. 4-2); this condition is called cutis marmorata (literally, marbled skin) and is not pathologic. It also is common in children with Down syndrome. Observe the effect of crying. Invariably, central cyanosis resulting from cardiac disease increases during crying, but do not make the baby cry until after you have listened to the heart.

Clinical manifestations of heart failure

When low cardiac output and high pulmonary venous pressure cause sufficient hemodynamic disturbance to produce clinical manifestations, cardiac enlargement is invariably present. Whether the disturbance involves primarily the left or the right ventricle, the left side of the thorax becomes prominent anteriorly (Fig. 10–1). Although this prominence may not be evident in the first month of life, it certainly will be evident by the age of 3 months. When respiratory distress due to heart failure has been present for 2 months or longer, the greater diaphragmatic contractions during respiration may produce a sulcus in the lower thorax, with outward flaring of the inferior rib cage edge. Therefore, look for a sulcus, left-sided chest prominence, abnormal chest or abdominal movement, an increased respiratory rate, and subcostal indrawing.

Palpation

Now lay your prewarmed hand very gently on the infant’s chest, remembering that the heart may not be in its normal position. With the tips of the first and second fingers of your right hand, depress the thorax just left of the xiphoid process (Fig. 10–2). Your fingertips are now lying on the right ventricle. A faint impulse is allowable, but if the heart is enlarged, a definite forceful movement will be present. When you perform this maneuver repeatedly in normal infants, you soon will be able to tell the difference between normal and abnormal findings. This distinction will help you make a quick decision about whether the 6-week-old baby who presents with respiratory distress has a cardiac or a respiratory problem.

Now depress the thorax in the apical area. Prominence of the apical impulse is diagnostically less helpful in infants than in older children, except in rare instances, such as in tricuspid atresia in which the right ventricle is hypoplastic. Then palpate in the second interspace at the left sternal border, where a prominent pulmonary artery pulsation may be elicited. Finally, place one index finger carefully in the suprasternal notch (Fig. 10–3), searching first for an abnormal pulsation and then for a thrill. Then work in the opposite direction, searching for thrills and palpable sounds. At this point, you should have made a reasonable appraisal of the child’s cardiac dynamics.

Liver size and position

Whether you are right- or left-handed, stand or sit on the baby’s right side to palpate for the liver. Use the tip of your right thumb and begin well down in the right lower quadrant of the abdomen, pressing inward and upward (Fig. 10–4). If the baby has just been fed, do not press very deeply. If the edge of the liver is soft, its margin may be difficult to detect; nevertheless, if the liver is enlarged, you should appreciate a sense of resistance as your thumb tip moves superiorly. If the edge is difficult to feel, use soft percussion, tapping the second digit of your left hand with the second digit of your right hand, beginning low in the right lower quadrant and placing the second digit of your left hand parallel to the liver edge (Fig. 10–5). You should be able to sense the change in the percussion note signifying the liver’s edge. Except in the presence of pulmonary hyperinflation, the edge of the liver normally should not be more than 1 to 2 cm below the costal margin.

Finally, remember that the liver can be ectopic (i.e., on the left side or up in the thorax).

Auscultation

Palpating the femoral pulses

Palpation of the pulses calls for gentleness, persistence, and patience, so make yourself comfortable before you begin. First, remove the baby’s diaper and palpate for femoral pulsations. Many babies do not appreciate having people poke around in their groins and may cry, urinate, or both. Femoral pulses are particularly difficult to appreciate in obese babies; thus, do not rush into a diagnosis of coarctation of the aorta if you have difficulty feeling them. If the femoral pulses are not palpable in an asthenic baby, however, there is cause for concern (see Fig. 4-20). Now palpate both brachial pulses again. If you can detect good brachial pulses and are certain that the femoral pulses are absent or greatly depressed, listen to the heart before measuring the blood pressure and upsetting the baby. Listen particularly for a high-pitched blowing systolic murmur, which is best heard anteriorly below the left clavicle and can be heard clearly in the left axilla and back, medial to the scapula.

Blood pressure

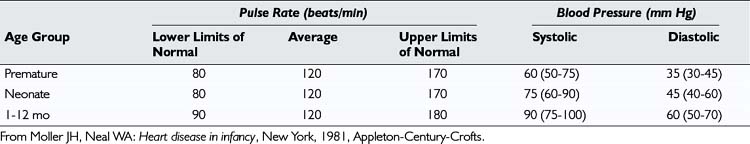

Although measuring the systemic blood pressure can be a difficult task, you should try to do so. The normal systolic blood pressure of an infant is between 60 and 80 mm Hg in both the arm and the leg (Table 10–1). The four methods of measuring blood pressure are (1) auscultatory, (2) palpatory, (3) visual (flush), and (4) Doppler.

For all methods of measuring blood pressure, first supinate the child’s arm to make the radial artery easily accessible. Apply the cuff, elevate the arm, and then inflate the cuff. Prior elevation of the arm (or opening and closing the hand) prevents the auscultatory gap phenomenon (Fig. 10–6). If this procedure is not followed, when you inflate the cuff and listen for Korotkoff sounds, as you decrease the pressure in the cuff you may hear a sound appear, then disappear, and then reappear as the pressure is further decreased. This phenomenon, known as the auscultatory gap, occurs because of increased vascular resistance distal to the cuff.

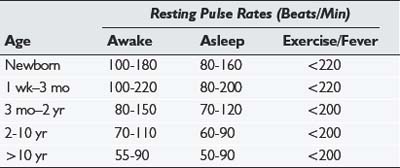

One way or another, a reliable blood pressure measurement must be obtained. If you suspect an aortic coarctation (i.e., if there is high pressure in the arm, an absence of femoral pulses, and a murmur), repeat the procedure in the thigh, using a blood pressure cuff of an appropriately larger size. Again, the manual Doppler method with the probe held on the posterior tibial or popliteal pulse is our preferred method of measuring blood pressure. The normal range of systolic and diastolic blood pressures for older children is shown in Table 10–2.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree