20

Cardiology

Chapter map

Most cardiac conditions present as a heart murmur, heart failure or the presence of cyanosis. Congenital heart disease is the most common cause of cardiac problems in children (Table 20.1). Primary myocardial disease and endocarditis are rare. Rheumatic fever (Section 23.3.6) and heart disease are still prevalent in developing countries, but are now rarely seen in Europe.

Doctors who look after children need to be able to recognize the possibility of heart disease, distinguish it from normal, and assess the urgency of the need for cardiological assessment. This can be difficult.

20.1.2 Pulmonary systolic murmur

20.2 Changes in circulation at birth

20.5 Classification of congenital heart disease

20.6 Surgical treatment of congenital heart disease

20.8.1 Supraventricular tachycardia (SVT)

20.8.2 Ventricular extrasystoles

20.1 Innocent murmurs

These murmurs (also called benign, functional and physiological) occur in children without any cardiac abnormality and are especially common in the newborn. Three main types of innocent murmur are recognized.

KEY POINTS

KEY POINTS- Cardiac murmurs do not always mean heart disease.

- Severe heart disease may occur without a murmur.

PRACTICE POINT Clinical features of an innocent murmur

PRACTICE POINT Clinical features of an innocent murmur- Asymptomatic

- Accentuated by fever/exercise

- Varies with respiration/posture

- Systolic/continuous

- Quiet (grade 1 or 2)

- Never harsh in character.

RESOURCE

RESOURCE20.1.1 Vibratory murmur

This is like the quiet buzzing of a bee. It is very short, mid-systolic and less obvious when the child sits up. It usually disappears by puberty.

20.1.2 Pulmonary systolic murmur

This is a soft, blowing ejection systolic murmur, heard at the upper left sternal edge. The differential diagnosis is a mild pulmonary stenosis.

20.1.3 Venous hum

This is due to blood cascading into the great veins. It is a blowing continuous murmur best heard above or below the clavicles. The hum is greatly diminished when the ipsilateral internal jugular vein is compressed, or when the child lies down flat.

20.2 Changes in circulation at birth

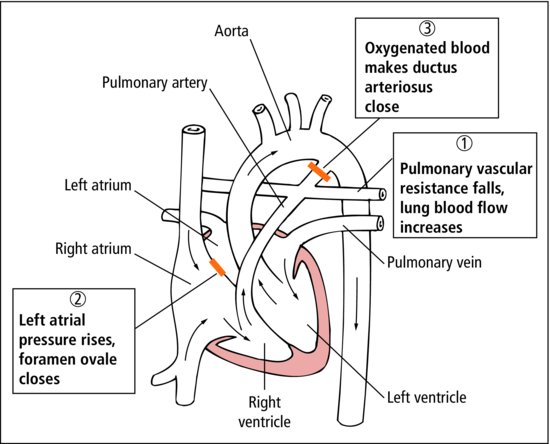

The changes that take place in the circulation at birth explain why symptoms of congenital heart disease may not occur until a few weeks after birth (Figure 7.1 and Figure 20.1). In the fetus, only 15% of the right ventricular blood enters the lungs, the rest passes through the ductus arteriosus to the descending aorta; the ductus is as large as the aorta.

After birth, the ductus closes within 10–15 h and the pulmonary artery pressure falls over the first 3 days of life. In lesions with a left-to-right shunt, the volume of blood shunted increases over the first weeks as pulmonary blood pressure falls.

RESOURCE

RESOURCE PRACTICE POINT Paediatric ECGs

PRACTICE POINT Paediatric ECGs20.3 Congenital heart disease

Congenital abnormalities of the heart (Table 20.1) are the most common important group of congenital anomalies. In Europe, most heart disease in children is congenital. There is a spectrum of severity in each defect from mild to severe, and in every lesion changes take place as a child grows, sometimes for better and sometimes for worse. Most severe symptoms occur in the first year of life, particularly in the newborn infant, and urgent investigation and treatment are required. Mild lesions cause no symptoms, are compatible with a normal life and require no treatment. Full initial assessment and follow up is important to prevent secondary changes in the myocardium.

Table 20.1 Congenital heart abnormalities

| Condition | Typical heart abnormality |

| Down syndrome | Atrioseptal defect |

| Trisomy 13 or 18 | Complex septal defects |

| Turner’s syndrome | Coarctation of the aorta |

| Marfan’s syndrome | Aortic aneurysm |

Heart defects occur in nearly 1% of live born infants. An abnormal heart may be found in around 10% of spontaneously aborted fetuses. Routine examination of the heart antenatally has led to an increased rate of fetal diagnosis.

RESOURCE

RESOURCE- Extra chromosomes (e.g. trisomy 21, Down syndrome)

- Missing chromosome (e.g. 46 XO, Turner syndrome)

- Chromosome mutations (e.g. 22q mutation)

- Congenital viral infections (e.g. rubella, toxoplasmosis)

- Maternal disease (e.g. diabetes mellitus, systemic lupus erythematosus)

- Therapeutic (e.g. warfarin, phenytoin)

- Toxins (e.g. excessive alcohol, illicit drugs)

20.3.1 Risk of endocarditis

Children with structural congenital heart disease are at increased risk of infective endocarditis. Antibiotic prophylaxis is no longer advised for procedures that might cause a bacteraemia (e.g. dental work). Evidence indicates: bacteraemias are commonly caused by everyday activities such as toothbrushing; a lack of association between endocarditis and prior interventional procedures; lack of efficacy of antibiotic prophylaxis. Instead, patients and families are given general advice about good oral health, when to suspect endocarditis and that there may be increased risk after invasive procedures (including body piercing).

RESOURCE

RESOURCE20.4 Neonatal presentations