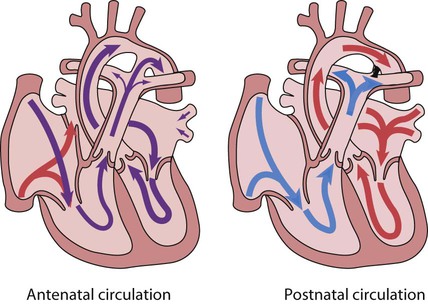

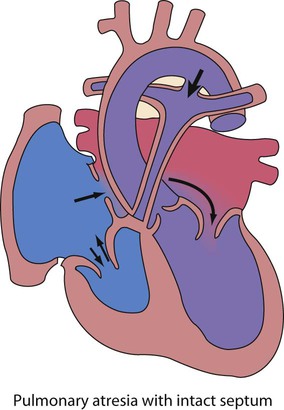

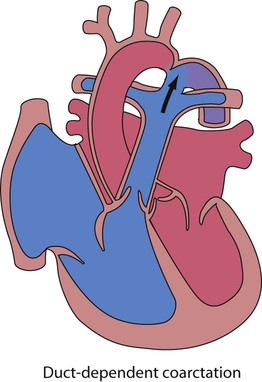

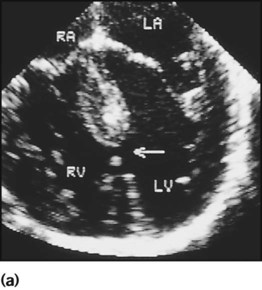

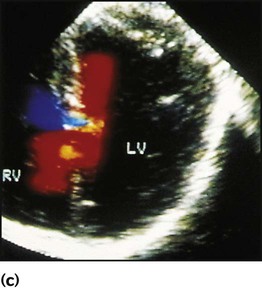

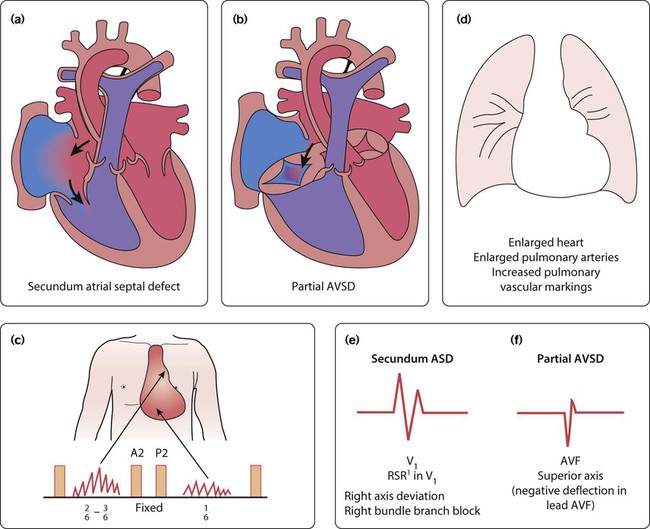

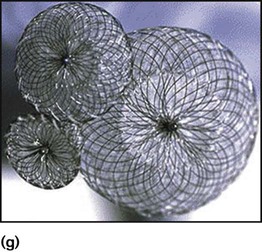

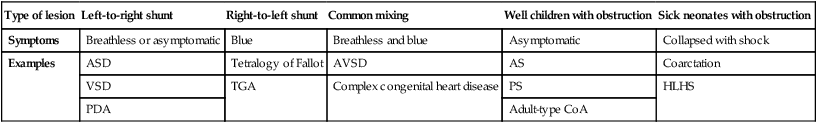

Recent developments in paediatric cardiac disease are: • Lesions are being increasingly identified on antenatal ultrasound screening • Most lesions are diagnosed by echocardiography, the mainstay of diagnostic imaging • MRI allows three-dimensional reconstruction of complex cardiac disorders, assessment of haemodynamics and flow patterns and assists interventional cardiology, reducing the need for cardiac catheterisation • Most defects can be corrected by definitive surgery at the initial operation • An increasing number of defects (60%) are treated non-invasively, e.g. persistent ductus arteriosus • New therapies are available to treat pulmonary hypertension and delay transplantation • The overall infant cardiac surgical mortality has been reduced from approximately 20% in 1970 to 2% in 2010. Genetic causes are increasingly recognised in the aetiology of congenital heart disease, now in more than 10%. These might affect whole chromosomes, point mutations or microdeletions (Table 17.1). Polygenic abnormalities probably explain why having a child with congenital heart disease doubles the risk for subsequent children and the risk is higher still if either parent has congenital heart disease. A small proportion are related to external teratogens. Table 17.1 Causes of congenital heart disease ASD, atrial septal defect; PDA, persistent ductus arteriosus; VSD, ventricular septal defect. In the fetus, the left atrial pressure is low, as relatively little blood returns from the lungs. The pressure in the right atrium is higher than in the left, as it receives all the systemic venous return including blood from the placenta. The flap valve of the foramen ovale is held open, blood flows across the atrial septum into the left atrium and then into the left ventricle, which in turn pumps it to the upper body (Fig. 17.1). Congenital heart disease presents with: In the first week of life, heart failure (Box 17.2) usually results from left heart obstruction, e.g. coarctation of the aorta. If the obstructive lesion is very severe then arterial perfusion may be predominantly by right-to-left flow of blood via the arterial duct, so-called duct-dependent systemic circulation (Fig. 17.2). Closure of the duct under these circumstances rapidly leads to severe acidosis, collapse and death unless ductal patency is restored (Case History 17.1). • Peripheral cyanosis (blueness of the hands and feet) may occur when a child is cold or unwell from any cause or with polycythaemia • Central cyanosis, seen on the tongue as a slate blue colour, is associated with a fall in arterial blood oxygen tension. It can only be recognised clinically if the concentration of reduced haemoglobin in the blood exceeds 5 g/dl, so it is less pronounced if the child is anaemic • Check with a pulse oximeter that an infant’s oxygen saturation is normal (≥94%). Persistent cyanosis in an otherwise well infant is nearly always a sign of structural heart disease. • Cardiac disorders – cyanotic congenital heart disease • Respiratory disorders, e.g. surfactant deficiency, meconium aspiration, pulmonary hypoplasia, etc. • Persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn (PPHN) – failure of the pulmonary vascular resistance to fall after birth • Infection – septicaemia from group B streptococcus and other organisms This is summarised in Table 17.2. Table 17.2 Types of presentation with congenital heart disease ASD, atrial septal defect; VSD, ventricular septal defect; PDA, patent ductus arteriosus; TGA, transposition of the great arteries; AVSD, atrioventricular; AS, aortic stenosis; PS, pulmonary stenosis; CoA, coarctation of the aorta; HLHS, hypoplastic left heart syndrome. If congenital heart disease is suspected, a chest radiograph and ECG (Box 17.3) should be performed. Although rarely diagnostic, they may be helpful in establishing that there is an abnormality of the cardiovascular system and as a baseline for assessing future changes. Echocardiography, combined with Doppler ultrasound, enables almost all causes of congenital heart disease to be diagnosed. Even when a paediatric cardiologist is not available locally a specialist echocardiography opinion may be available via telemedicine, or else transfer to the cardiac centre will be necessary. A specialist opinion is required if the child is haemodynamically unstable, if there is heart failure, if there is cyanosis, when the oxygen saturations are <94% due to heart disease and when there are reduced volume pulses. There are two main types of atrial septal defect (ASD): • Secundum ASD (80% of ASDs) (Fig. 17.5a) • Partial atrioventricular septal defect (primum ASD, pAVSD) (Fig 17.5b). Partial AVSD is a defect of the atrioventricular septum and is characterised by: • An inter-atrial communication between the bottom end of the atrial septum and the atrioventricular valves (primum ASD) • Abnormal atrioventricular valves, with a left atrioventricular valve which has three leaflets and tends to leak (regurgitant valve). • An ejection systolic murmur best heard at the upper left sternal edge – due to increased flow across the pulmonary valve because of the left-to-right shunt • A fixed and widely split second heart sound (often difficult to hear) – due to the right ventricular stroke volume being equal in both inspiration and expiration • With a partial AVSD, an apical pansystolic murmur from atrioventricular valve regurgitation. • Secundum ASD – partial right bundle branch block is common (but may occur in normal children), right axis deviation due to right ventricular enlargement (Fig. 17.5e) • Partial AVSD – a ‘superior’ QRS axis (mainly negative in AVF) (Fig 17.5f). This occurs because there is a defect of the middle part of the heart where the atrioventricular node is. The displaced node then conducts to the ventricles superiorly, giving the abnormal axis.

Cardiac disorders

Aetiology

Cardiac abnormalities

Frequency

Maternal disorders

Rubella infection

Peripheral pulmonary stenosis, PDA

30–35%

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE)

Complete heart block (anti-Ro and anti-La antibody)

35%

Diabetes mellitus

Incidence increased overall

2%

Maternal drugs

Warfarin therapy

Pulmonary valve stenosis, PDA

5%

Fetal alcohol syndrome

ASD, VSD, tetralogy of Fallot

25%

Chromosomal abnormality

Down syndrome (trisomy 21)

Atrioventricular septal defect, VSD

30%

Edwards syndrome (trisomy 18)

Complex

60–80%

Patau syndrome (trisomy 13)

Complex

70%

Turner syndrome (45XO)

Aortic valve stenosis, coarctation of the aorta

15%

Chromosome 22q11.2 deletion

Aortic arch anomalies, tetralogy of Fallot, common arterial trunk

80%

Williams syndrome (7q11.23 microdeletion)

Supravalvular aortic stenosis, peripheral pulmonary artery stenosis

85%

Noonan syndrome (PTPN11 mutation and others)

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, atrial septal defect, pulmonary valve stenosis

50%

Circulatory changes at birth

Presentation

Heart failure

Signs

Cyanosis

Type of lesion

Left-to-right shunt

Right-to-left shunt

Common mixing

Well children with obstruction

Sick neonates with obstruction

Symptoms

Breathless or asymptomatic

Blue

Breathless and blue

Asymptomatic

Collapsed with shock

Examples

ASD

Tetralogy of Fallot

AVSD

AS

Coarctation

VSD

TGA

Complex congenital heart disease

PS

HLHS

PDA

Adult-type CoA

Diagnosis

Left-to-right shunts

Atrial septal defect

Clinical features

Physical signs (Fig. 17.5c)

Investigations

ECG

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree