CHAPTER 45 Carcinoma of the ovary and fallopian tube

Carcinoma of the Ovary

Epidemiology

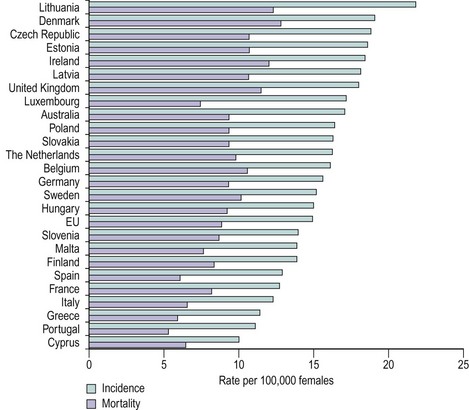

The incidence of ovarian carcinoma varies around the world, with lower rates recorded in Japan (3/100,000 women) and some of the highest rates recorded in the Nordic countries (20/100,000 women). Variations are also noted within Europe, with lower rates occurring in Mediterranean countries (Figure 45.1). In the UK, approximately 7000 cases are reported each year, with a mortality rate of 4500. As such, ovarian cancer remains the most lethal of the gynaecological cancers, and the fourth most common malignant cause of death in women. The majority of women present with disease spread outside the ovaries, normally stage III–IV disease (Table 45.1), and this has a 5-year survival rate of approximately 40%. Ovarian cancer is mainly a disease of postmenopausal women, with the bulk of cases occurring in women aged 50–75 years. The main histological tumours are epithelial in origin, accounting for 90% of cases. Serous tumours are the most common, and as tubal tumours are also serous, accurate identification of the true primary site of disease can be difficult.

Figure 45.1 Age-standardized incidence and mortality rates for ovarian cancer, European Union, 2002 estimates.

Table 45.1 FIGO staging for ovarian cancer

| Stage I | Growth limited to the ovaries |

| Stage IA | Growth limited to one ovary, no ascites, no tumour on external surface, capsule intact |

| Stage IB | Growth limited to both ovaries, no ascites, no tumour on external surface, capsule intact |

| Stage IC | Tumour as for stage IA or B, but tumour on surface of one or both ovaries or capsule ruptured or positive ascites/peritoneal washings |

| Stage II | Tumour as for stage IC, but growth involving one or both ovaries with pelvic extension |

| Stage IIA | Extension and/or metastases to the uterus and/or tubes |

| Stage IIB | Extension to other pelvic tissue |

| Stage IIC | Tumour as for stage IIA or B, but tumour on surface of one or both ovaries or capsule ruptured or positive ascites/peritoneal washings |

| Stage III | Tumour involving one or both ovaries with peritoneal implants outside the pelvis and/or positive retroperitoneal or inguinal nodes. Includes superficial liver metastases or histologically proven malignant extension to small bowel/omentum |

| Stage IIIA | Tumour grossly limited to true pelvis with negative nodes, but histologically confirmed microscopic seeding of abdominal peritoneal surfaces |

| Stage IIIB | Tumour involving one or both ovaries with histologically confirmed implants of abdominal peritoneal surfaces, none exceeding 2 cm in diameter |

| Stage IIIC | Abdominal implants greater than 2 cm in diameter and/or positive retroperitoneal or inguinal nodes |

| Stage IV | Growth of one or both ovaries with distant metastases, e.g. parenchymal liver metastases, or cytologically proven pleural effusion |

Aetiology

The main theory recounted for many years, called the ‘incessant ovulation theory’, is derived from the association between a woman’s number of lifetime ovulations and the risk of ovarian cancer. The greater the number of ovulations, the greater the risk of ovarian cancer. Prevention of ovulation by either pregnancy or use of the combined contraceptive pill should reduce the risk of ovarian cancer, and this has indeed been noted. Some of the proposed explanations for this theory are that the milieu of rapid cellular turnover (in the development of the ovum), the injury caused with release of the ovum and stromal invagination (which occurs at ovulation) contribute to the risk of malignancy. However, more complex factors are likely to be involved. For example, the progesterone in the contraceptive pill is known to cause apoptosis of ovarian cells, and this is being investigated in a phase II trial by the Gynecologic Oncology Group in high-risk patients to determine the apoptotic effect on ovarian tissues. This may potentially become a preventative therapy in the future.

Infertility

For many years, it has been recognized that there may be an association between infertility and risk of ovarian cancer. The relationship has never been absolutely clarified, and there are many conflicting reports in the literature (Mahdavi et al 2006, Jensen et al 2009). The difficulties mainly relate to the information available, as the types of drugs used, their duration of use and the outcome of pregnancies were not well recorded in many reports. One proposal associating the use of drug-induced ovulation and potential malignant transformation was seen in the increased ovarian cellular dyplasia in ovaries removed from women with a history of in-vitro fertilization treatment (Chene et al 2009). However, further larger longitudinal studies are needed to confirm the situation regarding infertility and ovarian cancer.

Endometriosis

Endometriosis affects approximately one in eight women. The notable tumours associated with endometriosis are ovarian clear cell carcinomas. Endometrioid tumours are also known to have a relationship with endometriosis, but this association is weaker. An interesting fact is that clear cell tumours are most prevalent in Japan, despite the fact that Japan has the lowest incidence of ovarian cancer in the world. The concept that endometriosis is a premalignant condition has been proposed, based on the ability of endometriosis to metastasize, and also as it is found in association with ovarian malignancies. There is a need for further work in this area, but it is interesting to note that women with endometriosis also have a higher relative risk of developing other cancers (Melin et al 2007).

Molecular biology

One aspect of ovarian cancer is the somewhat limited understanding of the tumour biology and the natural history of the condition itself. Most patients present with advanced disease and it is often considered that ovarian cancer has a rapid growth phase, hence the late presentation with a short history of symptoms. Some work on symptoms in ovarian cancer suggests that these may be present some time prior to diagnosis (Goff et al 2007), and the natural progression of the disease may be different to previous assumptions. However, this requires further research before becoming acceptable.

In ovarian cancer, molecular markers have been researched although there is a lack of true understanding of tumour biology. Tumour vascular proteins (Buckanovich et al 2007) have been shown to have different expression in ovarian malignancies compared with normal, and with the development of antivascular endothelial growth factor therapies with a spectrum of tumour vascular proteins now recognized, further therapies may be developed. Serum mesothelin level is another marker noted to be elevated in ovarian cancer and to have a direct correlation with disease stage, and this could have potential use in screening (Huang et al 2006). Proteomic studies are used increasingly and should yield some valuable information to facilitate the understanding of ovarian cancer (Boyce and Kohn 2005).

Classification of ovarian tumours

The most commonly used classification of ovarian tumours was defined by the World Health Organization (Scully 1999). This is a morphological classification that attempts to relate the cell types and patterns of the tumour to tissues normally present in the ovary. The primary tumours are thus divided into those that are of epithelial type (implying an origin from surface epithelium and the adjacent ovarian stroma), those that are of sex cord gonadal type (also known as sex cord stromal type or sex cord mesenchymal type, and originating from sex cord mesenchymal elements) and those that are of germ cell type (originating from germ cells). A simplified classification is given in Table 45.2.

Table 45.2 Simplified classification of ovarian cancers

| Epithelial origin | |

| Germ cell origin | |

| Others |

Pathology of epithelial tumours

Epithelial tumours are derived from the ovarian surface epithelium, which is a modified mesothelium with a similar origin and behaviour to the Müllerian duct epithelium, and from the adjacent distinctive ovarian stroma. They are subclassified according to epithelial cell type (serous, mucinous, endometrioid, clear, transitional, squamous); the relative amount of epithelial and stromal component (when the stromal is larger than the cystic epithelial component, the suffix ‘fibroma’ is added); and the macroscopic appearance (solid, cystic, papillary). They account for 50–55% of all ovarian tumours, but their malignant forms represent approximately 90% of all ovarian cancers in the Western world (Koonings et al 1989). Well-differentiated epithelial carcinomas are more often associated with early-stage disease, but the degree of differentiation does correlate with survival, except in the most advanced stages. Diploid tumours tend to be associated with earlier stage disease and a better prognosis. Histological cell type is not in itself prognostically significant.

Endometrioid carcinoma

Endometrioid carcinomas are ovarian tumours that resemble the malignant neoplasia of epithelial, stromal and mixed origin that are found in the endometrium (Czernobilsky et al 1970). They account for 2–4% of all ovarian tumours. They are accompanied by ovarian or pelvic endometriosis in 11–42% of cases, and a transition to endometriotic epithelium can be seen in up to 30% of cases. The pathologist must distinguish metaplastic and reactive changes in endometriosis from true neoplastic changes.