CHAPTER 39 Cancer of the uterine cervix

Epidemiology

Cervical cancer is the most common gynaecological malignancy in the world with an estimated 493,000 new cases diagnosed each year (Ferlay et al 2004). It accounts for nearly 10% of all cancers in women. Although the incidence of cervical cancer has decreased in industrialized countries in the past 20 years, it still remains a major problem in the developing world. In most parts of Africa, South-Central Asia and Central America, cervical cancer accounts for 7–13% of all newly diagnosed cancers, with an incidence of 30–40 new cases per 100,000 population (Cancer Research UK, 2005).

In the UK, 2800 patients are diagnosed with cervical cancer per year, which accounts for approximately 2% of all female cancer cases, and 950 patients die from the disease (Cancer Research UK, 2005). With the introduction of the cervical screening programme in the UK, the incidence of cervical cancer has decreased from 16/100,000 in 1985 to 8/100,000 in 2005, while the incidence of carcinoma in situ has risen because of early detection with screening (Cancer Research UK, 2005). Carcinoma in situ is most common in women aged 35–39 years, while the incidence of cervical cancer is highest in women aged 30–34 years (17/100,000). The distribution of cervical cancer is bimodal, with a second peak reached in women aged over 85 years (14/100,000) (Cancer Research UK, 2005). Only 30% of cervical cancers are detected by screening, and the majority of cases occur in women who have never had a smear test or who have not been regular participants in the screening programme.

Aetiology

Epidemiological studies have long indicated a positive correlation between sexual activity and cervical cancer (Schiffman and Brinton 1995). Promiscuity, a sexual partner with promiscuous sexual behaviour and early age at first sexual intercourse have all been associated with a high risk of cervical cancer. It has been well demonstrated that human papilloma virus (HPV) infection is the major and probably a necessary causal factor, enhanced by several cofactors for both squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma of the cervix (Muñoz et al 1992, Schiffman et al 1993, Bosch et al 2002). HPV viral particles have been detected in almost all cases of cervical cancer (99.7%) (Walboomers and Meijer 1997, Franco et al 1999, Walboomers et al 1999).

Human papilloma virus

To date, more than 200 subtypes of HPV have been identified. According to oncogenic potential, HPVs can be classified as low-risk or high-risk types (Table 39.1) (Duenas-Gonzalez et al 2005, Smith et al 2007). Approximately 75% of cervical cancers are related to HPV 16 and 18 in Europe, and 90% of genital warts are caused by HPV 6 and 11 (Smith 2003). However, the distribution of HPV subtypes varies in other parts of the world (Smith et al 2007).

Table 39.1 Risk groups of human papilloma virus (HPV)

| High-risk HPV | 16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 45, 51, 52, 58, 59, 68, 73, 82 |

| Low-risk HPV | 6, 11, 40, 42, 43, 44, 54, 61, 70, 72, 81 |

It is estimated that nearly 80% of sexually active women will acquire an HPV infection during their lifetime, while oncogenic subtypes are identified in 15% of the population (Brown et al 2005, Dunne et al 2007). Ninety percent of HPV infections will be eradicated by the host immune system, and only a minority of women will develop preinvasive disease or cancer (Pagliusi and Teresa Aguado 2004). The prevalence of HPV infection decreases with age, from approximately 20% in women aged 20–25 years to approximately 5% in women aged 50 years (Woodman et al 2001).

Cofactors

Cigarette smoking

Cigarette smoking has been linked with a higher risk of cervical cancer and has been demonstrated to be an independent risk factor (Winkelstein 1990, Kapeu et al 2009). High concentrations of nicotine metabolites have been detected in cervical mucus, and their molecular interaction with fragile histidine triad (FHIT) tumour suppressor gene has been investigated (Schiffman et al 1987, Holschneider et al 2005). The loss of function of FHIT plays an important role in early carcinogenesis (Pichiorri et al 2008). In comparison with non-smokers, smokers have impaired immune responses in the cervical epithelium and produce reduced levels of HPV 16/18 antibodies (Simen-Kapeu et al 2008).

A recent meta-analysis confirmed that smoking is an independent risk factor for squamous cell cervical cancer, but failed to demonstrate the same for adenocarcinoma (Berrington de González et al 2004).

Oral contraceptives

The association between long-term oral contraceptive (OC) use and cervical cancer is unclear. Recent analyses have shown an increased risk (relative risk 1.3–1.9) of cervical cancer amongst OC users (Smith 2003, Appleby et al 2007, Hannaford et al 2007). In contrast, others have reported that sexual behaviour differs between OC users and non-users, and that OC use is not an independent risk factor (Miller et al 2004, Syrjänen et al 2006).

Immunodeficiency

It has been observed that patients with immunodeficiency disorders, those on immunosuppressive therapy and those with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection are at higher risk of developing anogenital HPV-related premalignant changes and cancers. Cervical cancer is an acquired-immunodeficiency-syndrome-defining disease. One meta-analysis estimated a six-fold increased risk of developing cervical cancer for patients with HIV infection, and a two-fold increased risk for those with previous transplant surgery (Grulich et al 2007).

HPV vaccination

Cervical cytology

Two types of HPV vaccine have been developed: the bivalent Cervarix targeting HPV 16 and 18, and the quadrivalent Gardasil for HPV 6, 11, 16 and 18. The efficacy of Gardasil and Cervarix has been demonstrated in large, prospective, randomized trials (FUTURE II and PATRICIA) (FUTURE II Study Group 2007, Paavonen et al 2007). The vaccines are prophylactic and are not effective in patients with existing HPV infection. There is some cross-protection against other high-risk types of HPV.

Clinical Presentation

The positive predictive value of postcoital and intermenstrual bleeding for the diagnosis of cervical cancer in younger women is very low (Shapley et al 2006). Only 2% of patients with postcoital bleeding will be diagnosed with cervical cancer (Shapley et al 2006).

Diagnosis and Staging

Imaging in cervical cancer

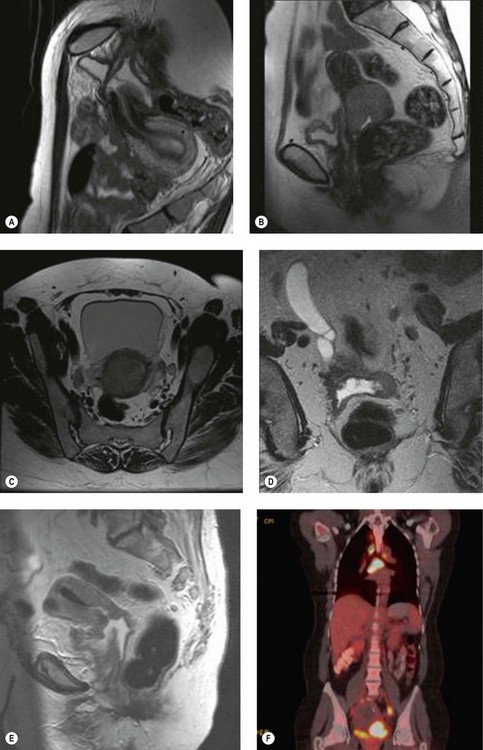

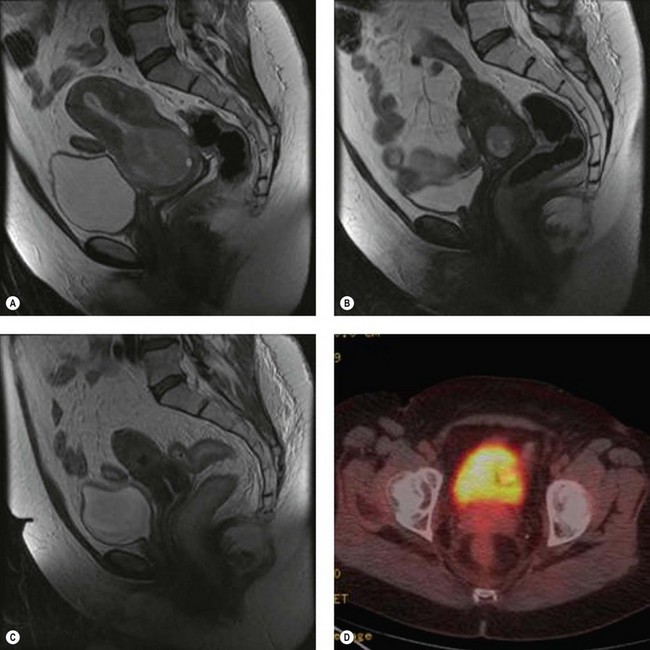

Positron emission tomography (PET) is a functional scan that assesses the increased uptake of fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG). Organs with high metabolic activity (liver, brain, neoplastic tissue) have high FDG uptake. Addition of CT to PET (PET–CT) provides improved assessment of tumour localization. PET–CT has been used to assess para-aortic nodal status to facilitate planning of radiotherapy fields (Figure 39.1F) (Grigsby et al 2001). A further role of PET–CT is to assess the response to primary chemoradiotherapy, as well as early detection of cancer recurrences (Figure 39.2D).

Laparoscopic para-aortic lymph node sampling

Laparoscopic para-aortic lymph node sampling has been performed to assess the para-aortic lymph nodes; however, the only prospective randomized study failed to confirm therapeutic benefit (Lai et al 2003). The detection of micrometastasis in the para-aortic nodes has been used to modify radiation treatment fields (Leblanc et al 2007). Superiority of lymphadenectomy over PET–CT in assessment of the para-aortic nodes has not been established.

Staging

The International Federation of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (FIGO) staging of cervical cancer is based on clinical findings and, in the early stages, on the microscopic extent of the disease, and is not changed by intraoperative findings or the postoperative histological result (Table 39.2). When doubt exists regarding the stage of a particular cancer, the earlier stage should be chosen.

Table 39.2 Revised FIGO staging of cervical cancer (2009)

| Stage I | The carcinoma is strictly confined to the cervix (extension to the corpus would be disregarded) |

| IA | Invasive carcinoma which can be diagnosed only by microscopy, with deepest invasion ≤5.0 mm and largest extension ≤7.0 mm |

| IA1 | Measured stromal invasion of ≤3.0 mm in depth and horizontal extension of ≤7.0 mm |

| IA2 | Measured stromal invasion of >3.0 mm and not >5.0 mm with an extension of not >7.0 mm |

| IB | Clinically visible lesions limited to the cervix uteri or preclinical cancers greater than stage IA* |

| IB1 | Clinically visible lesion ≤4.0 cm in greatest dimension |

| IB2 | Clinically visible lesion >4.0 cm in greatest dimension |

| Stage II | Cervical carcinoma invades beyond the uterus, but not to the pelvic wall or to the lower third of the vagina |

| IIA | Without parametrial invasion |

| IIAl | Clinically visible lesion ≤4.0 cm in greatest dimension |

| IIA2 | Clinically visible lesion >4.0 cm in greatest dimension |

| IIB | With obvious parametrial invasion |

| Stage III | The tumour extends to the pelvic wall and/or involves lower third of the vagina and/or causes hydronephrosis or non-functioning kidney§ |

| IIIA | Tumour involves lower third of the vagina, with no extension to the pelvic wall |

| IIIB | Extension to the pelvic wall and/or hydronephrosis or non-functioning kidney |

| Stage IV | The carcinoma has extended beyond the true pelvis or has involved (biopsy proven) the mucosa of the bladder or rectum. A bullous oedema, as such, does not permit a case to be allotted to stage IV |

| IVA | Spread of the growth to adjacent organs |

| IVB | Spread to distant organs |

* All macroscopically visible lesions, even with superficial invasion, are allotted to stage IB carcinomas. Invasion is limited to a measured stromal invasion with a maximal depth of 5.0 mm and a horizontal extension of not >7.0 mm. Depth of invasion should not be >5.0 mm taken from the base of the epithelium of the original tissue — superficial or glandular. The depth of invasion should always be reported in mm, even in those cases with ‘early (minimal) stromal invasion’ (∼1.0 mm). The involvement of vascular/lymphatic spaces should not change the stage allotment.

§ On rectal examination, there is no cancer-free space between the tumour and the pelvic wall. All cases with hydronephrosis or non-functioning kidney are included, unless they are known to be due to another cause.

Surgical staging in cervical cancer is an issue that continues to generate discussion. Should lymph node status influence the staging? Should further substages be included? Should the histological findings and cross-sectional imaging influence the process of staging? A consensus statement from the International Gynecological Cancer Society meeting in 2006 reported as follows (Odicino et al 2007).

Stage IIA: should be subgrouped similar to stage IB based on tumour size as stage IIA1 with tumour size less than 4 cm with involvement of up to two-thirds of the upper vagina, and stage IIA2 with tumour size greater than 4 cm with involvement of up to two-thirds of the upper vagina.

Stage IIA: should be subgrouped similar to stage IB based on tumour size as stage IIA1 with tumour size less than 4 cm with involvement of up to two-thirds of the upper vagina, and stage IIA2 with tumour size greater than 4 cm with involvement of up to two-thirds of the upper vagina.Histology

Adenocarcinoma is the second most common histological type and represents 20% of cervical cancers. The proportion of adenocarcinomas compared with squamous cell carcinomas has increased significantly over the past three decades. The cause of this change is two-fold: relative, due to the gradual decrease in incidence of squamous cell carcinoma following the introduction of the cervical screening programme; and absolute, probably due to factors such as increased use of OCs (Ursin et al 1994, Smith et al 2000, Sasieni and Adams 2001). The gross appearance of adenocarcinomas is similar to squamous lesions; however, nearly 15% of patients present with clinically non-apparent lesions due to the endophytic expansion of the cancer (barrel-shaped cervix).

Neuroendocrine cervical carcinomas are rare histological subtypes, accounting for less than 5% of cervical cancers. They are characterized by highly aggressive clinical behaviour, manifesting as early nodal and distant diseases in more than half of patients. This results in poor survival despite multimodal treatment. Neuroendocrine cervical carcinomas are similar to the neuroendocrine cancers of the lung, both clinically and histologically. There are four subgroups: classical carcinoid, atypical carcinoid tumour, neuroendocrine large cell carcinoma and neuroendocrine small cell (oat cell) carcinoma (Albores-Saavedra et al 1997).

Treatment of Cervical Cancer

Surgical management

The method of surgical treatment of cervical cancer depends on the stage of disease, tumour volume, histological features, patient’s desire for future fertility and performance status. Treatment options for different stages of cervical cancer are shown in Table 39.3. The Wertheim-Meigs radical hysterectomy with pelvic lymphadenectomy has been the standard treatment for over a century in patients with stage IA2–IIA cervical cancer. Critical analysis of the data on the role of parametrectomy and pelvic lymphadenectomy has changed the practice significantly, and narrowed the indication for the radical operation. In stage IA2 and low-volume stage IB1 (<500 m3) cervical cancer, the risk of parametrial involvement is low (<2%); therefore, simple hysterectomy is recommended (Stegeman et al 2007). Novel developments in surgical technique, such as fertility-sparing surgery (trachelectomy), laparoscopic radical hysterectomy, pelvic lymphadenectomy and para-aortic lymphadenectomy, have been developed and are practised increasingly. Sentinel node biopsy in cervical cancer is also being explored (Levenback et al 2002).

Table 39.3 Management of cervical cancer

| Stage | Treatment | LND |

|---|---|---|

| IA1 | Cone biopsy/simple trachelectomy/simple hysterectomy | No |

| IA2 | Cone biopsy/simple trachelectomy/simple hysterectomy | +/− (variable practice) |

| IA1/IA2 + LVSI | Cone biopsy/simple trachelectomy/simple hysterectomy | + |

| IB1: low volume (<500 mm3) | Simple trachelectomy/simple hysterectomy | + |

| IB1: <2 cm diameter | Radical trachelectomy/radical hysterectomy | + |

| IB1: 2–4 cm diameter | Radical hysterectomy | + |

| IB2/IIA | Chemoradiation/radical hysterectomy | + |

| IIB–IVA | Chemoradiation/palliative surgery | |

| IVB | Chemotherapy +/− palliative radiotherapy |

LND, lymph node dissection.