7 Burns

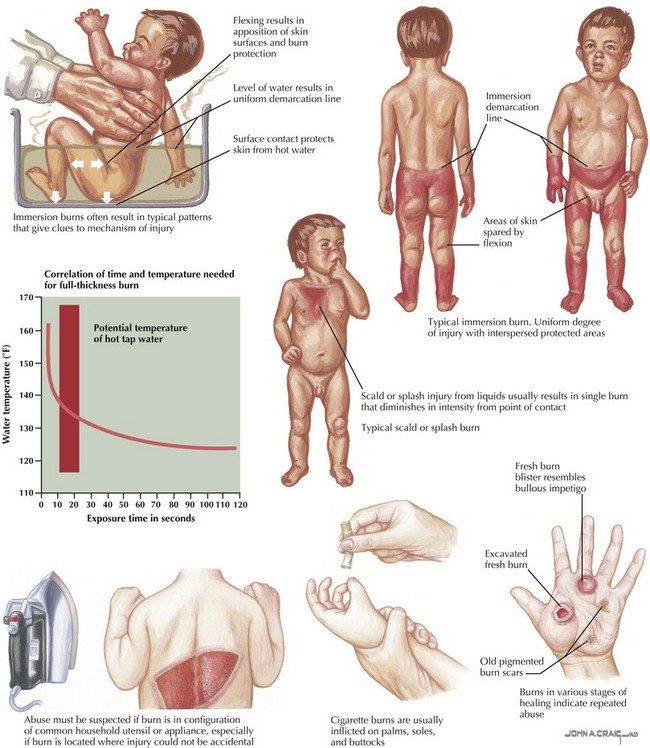

Burns and fire-related injuries account for significant morbidity and mortality in the pediatric population. In children younger than 18 years of age, fires and burns are the third leading cause of death from unintentional injury in the United States. Approximately one-third of all burns occur in children and adolescents younger than 20 years of age. Boys and children younger than 5 years of age are at highest risk of burn injuries. Burns may be thermal (resulting from flame, scald, steam, or contact), electrical, or chemical in cause (Figure 7-1). In children younger than 5 years of age, scalds resulting from bathing injuries or hot liquid spills account for the majority of burns. Fire and flames are the leading causes of burns in children older than 5 years of age. Electrical burns are seen primarily in adolescents. Child abuse accounts for up to 20% of burns in children and thus needs to be considered in all cases of pediatric burns, particularly in those with inconsistent mechanisms or specific patterns of injury (see Chapter 12). Carbon monoxide poisoning can occur with smoke inhalation and is responsible for many early deaths related to fire.

Etiology and Pathogenesis

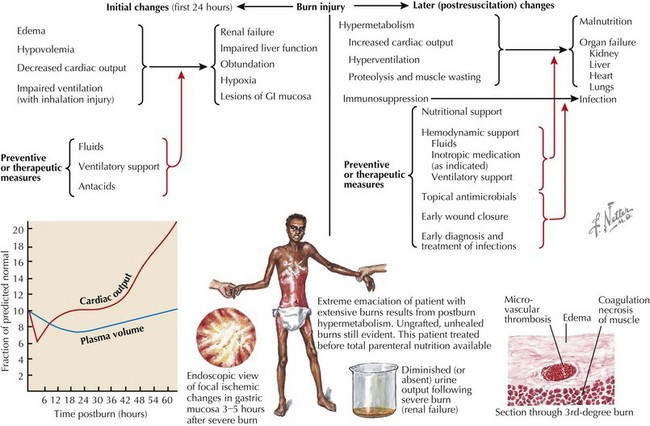

Larger burns may produce systemic effects (Figure 7-2). Bacterial colonization of burned tissue may result in infection caused by disruption of the protective epidermal barrier and the inability of immune system elements and antibiotic agents to penetrate burned tissue. Capillary permeability is increased by the release of osmotically active substances into the interstitial space and the release of vasoactive mediators into the systemic circulation. Edema with resulting intravascular hypovolemia results in both injured and noninjured tissues. Circulating factors reduce myocardial function, thus decreasing cardiac output. Direct heat damage and a microangiopathic hemolytic process result in acute hemolysis of erythrocytes. All of these acute processes may result in renal failure, liver dysfunction, mental status changes, and hypoxia. After the initial injury, a hypermetabolic and immunosuppressive state may ensue, resulting in malnutrition, infection, and multisystem organ failure.

Clinical Presentation

The diagnosis of a burn injury is typically evident from the patient’s history and clinical presentation. The differential diagnosis includes erythroderma, toxic epidermal necrolysis, and staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome; however, these are quickly distinguished from burns based on history and presentation. Certain patterns of injury are classic for an intentional burn as a result of child abuse (Figure 7-3). Scald injuries of the buttocks and thighs accompanied by perineal or foot injury that spares the flexion creases is classic for intentional injury with defensive posturing. Symmetric burns of the hands or feet with clear lines of immersion are classic for forced submersion injuries. Small, round, deep burns are suggestive of intentional cigarette burns. Any deep wound with some geometric pattern may suggest a contact burn, such as an iron. Suspicion should be raised for abuse in any case with a nonspecific history, a mechanism that is inconsistent with the clinical presentation, delayed presentation, or a classic injury pattern.

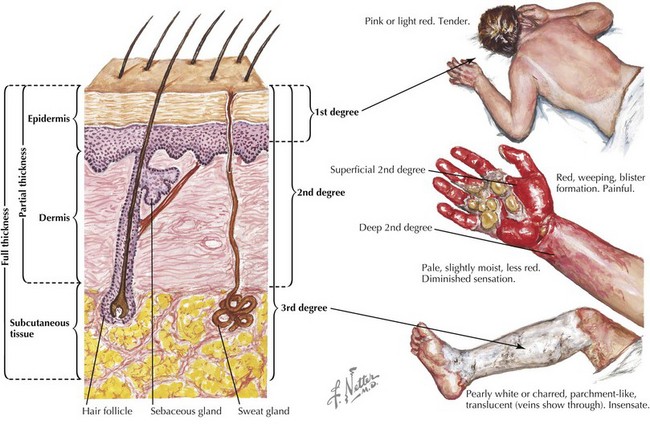

Burns are traditionally classified by the depth of skin injury (Figure 7-4). Superficial burns, formerly known as first-degree burns, involve the epidermis only and present with pain and redness over the affected areas without significant edema or blistering. These burns resolve in 3 to 5 days without residual scarring. Of note, superficial burns are not included in burn surface area (BSA) calculations.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree