37 Bronchiolitis and Wheezing

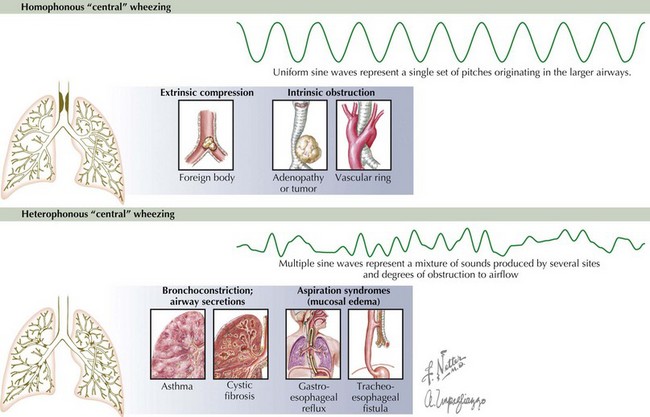

Wheezing is heterophonous or polyphonic in nature when there is diffuse narrowing of the airways. This widespread involvement of the airways produces a mixture of sounds associated with various degrees of obstruction to airflow. Multiple varied degrees of obstruction typically occur in the presence of bronchospasm, edema, or intraluminal secretions. The most common causes of heterophonous wheezing in the pediatric population are viral bronchiolitis and asthma (see Chapter 38). Conversely, homophonous wheezing refers to a single set of pitches that originates in the larger airways but that can be transmitted widely. Common causes of homophonous wheezing include tracheomalacia, bronchomalacia, foreign body aspiration, and anatomic compression of the airways (Figure 37-1).

Etiology and Pathogenesis

The majority of wheezing in infants is caused by viral bronchiolitis or asthma, but many other entities can also cause wheezing at this age (Box 37-1).

Box 37-1 Differential Diagnosis of Wheezing in Infants and Young Children

Bronchiolitis

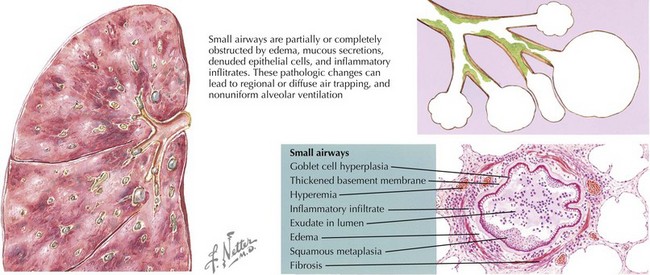

The infectious cause of acute bronchiolitis typically includes viruses with specific tropism for bronchiolar epithelium. Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) is responsible for more than 50% of cases, but other viruses are increasingly recognized as causes of this clinical entity. Viral infection of the lower airways can induce severe changes in the epithelial cell and mucosal surfaces of the human respiratory tract. Bronchiolar epithelial cell necrosis, ciliary disruption, and peribronchiolar lymphocytic infiltration are the earliest lesions. Edema of the small airways and mucus secretion, mixed with denudated epithelial cells, elicits obstruction and narrowing of the airways (see Figure 37-2). The generation of atelectasis is often associated with ventilation/perfusion mismatch and consequent hypoxemia. Heterogeneous ventilation and dynamic collapse of the airways during exhalation can lead to air trapping and pulmonary hyperinflation (see Figure 37-2). With severe obstructive lung disease and respiratory muscle fatigue, hypercapnia can also arise.

Asthma

Asthma is another important cause of wheezing in infants and children (see Chapter 38). This clinical entity is characterized by recurrent episodes of airway obstruction that are at least partially reversible with bronchodilators. Another pathogenic feature of the disease is chronic inflammation of the airways. Whereas extensive bronchiolar epithelial cell necrosis and T-helper cell type 1 (Th1) cytokines like interferon-γ are present in viral bronchiolitis, inflammation in asthma is often driven by allergic (Th2) cytokines such as interleukin-13 (IL-13), IL-4, and IL-5. Other abnormalities of the asthmatic airway include constriction and hypertrophy of the airway smooth muscle, mucosal edema, hypertrophic mucous glands, and sometimes eosinophilic infiltration.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree