11 Breastfeeding

Breastfeeding Recommendations

Breastfeeding Recommendations

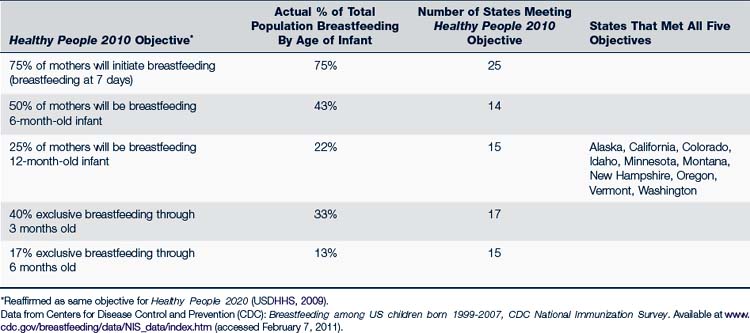

Proposed breastfeeding goals for Healthy People 2020 reaffirm those from the Healthy People 2010 document: 75% of mothers will initiate breastfeeding in the neonatal period; 50% will be breastfeeding at 6 months, and 25% at 1 year of age (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [USDHHS], 2009). Breastfeeding rates have increased in the U.S. (Table 11-1), and three out of four new mothers initiate breastfeeding, meeting one of the Healthy People goals. Exclusive breastfeeding until 3 to 6 months and continued breastfeeding from 6 to 12 months still fall short of desired goals, however (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2010). In 2011, the U. S. Department of Health and Human Services issued a report entitled The Surgeon General’s Call to Action to Support Breastfeeding (2011). Twenty actions were identified to support breastfeeding and include:

1. Give mothers the support they need to breastfeed their babies.

2. Develop programs to educate fathers and grandmothers about breastfeeding.

3. Strengthen programs that provide mother-to-mother support and peer counseling.

4. Use community-based organizations to promote and support breastfeeding.

5. Create a national campaign to promote breastfeeding.

6. Ensure that the marketing of infant formula is conducted in a way that minimizes its negative impact on exclusive breastfeeding.

7. Ensure that maternity care practices throughout the United States are fully supportive of breastfeeding.

8. Develop systems to guarantee continuity of skilled support for lactation between hospitals and health care setting in the community.

9. Provide education and training in breastfeeding for all health professionals who care for women and children.

10. Include basic support to breastfeeding as a standard of care for midwives, obstetricians, family physicians, nurse practitioners, and pediatricians.

11. Ensure access to services provided by the International Board of Certified Lactation Consultants.

12. Identify and address obstacles to greater availability of safe banked donor milk for fragile infants.

13. Work toward establishing paid maternity leave for all employed mothers.

14. Ensure that employers establish and maintain comprehensive high-quality lactation support programs for their employees.

15. Expand the use of programs in the workplace that allow lactating mothers to have direct access to their babies.

16. Ensure that all child care providers accommodate the needs of breastfeeding mothers and infants.

17. Increase funding of high-quality research on breastfeeding.

18. Strengthen existing capacity and develop future capacity for conducting research on breastfeeding.

19. Develop a national monitoring system to improve the tracking of breastfeeding rates as well as the policies and environmental factors that affect breastfeeding.

20. Improve national leadership on the promotion and support of breastfeeding.

TABLE 11-1 Healthy People 2010 Objectives: Initiation and Duration of Breastfeeding for Children Born in 2007

Providers can make a major contribution to breastfeeding’s success by supporting these actions.

Hospital-Based Support

Hospital-Based Support

The Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative

• Have a written breastfeeding policy that is routinely communicated to all health care staff.

• Prepare all health care staff in skills necessary to implement this policy.

• Inform all pregnant women about the benefits and management of breastfeeding.

• Help mothers initiate breastfeeding within one half hour of birth.

• Show mothers how to breastfeed and how to maintain lactation even if they are separated from their infants.

• Give newborn infants no food or drink other than breast milk, unless medically indicated.

• Practice rooming-in (i.e., allow mothers and infants to remain together) 24 hours a day.

• Encourage unrestricted breastfeeding.

• Give no artificial teats or pacifiers (also called dummies or soothers) to breastfeeding infants.

• Foster the establishment of breastfeeding support groups and refer mothers to them on discharge from the hospital or clinic.

Benefits of Breastfeeding

Benefits of Breastfeeding

With rare exception, breast milk is the ideal food for a human infant. Each mammalian species provides milk uniquely suited to its offspring, and milk from the human breast is no exception. It is a living fluid rich in vitamins, minerals, fat, proteins (including immunoglobulins and antibodies), and carbohydrates (especially lactose). It contains enzymes and cellular components, including macrophages and lymphocytes, in addition to many other constituents that offer ideal support for growth and maturation of the human infant. As the infant grows and develops, the properties of the breast milk change. The sequence of colostrum, transitional milk, and mature milk meets the changing nutritional needs of the newborn and infant. Thus the milk of a mother of a 9-month-old has different concentrations of fat, protein, and carbohydrate and different physical properties, such as pH, when compared with the milk of the mother of a newborn or 1-month-old. In addition, some of the constituent properties in the milk are different from one time of day to another.

Initiating breastfeeding is crucial; the infant enjoys health benefits with every day of breastfeeding. Maintaining breastfeeding is also crucial; there is evidence, for example, that infants who are breastfed for 6 months have less risk for infection than those breastfed for 4 months (Chantry et al, 2006). However, exclusive, prolonged breastfeeding may actually contribute to health problems. Pesonen and associates found that infants exclusively breastfed for 9 months or longer had an increased incidence of atopic dermatitis and food hypersensitivity in childhood (Pesonen et al, 2006). Complementary foods should be added to the infant diet by 6 months of age (see Chapter 10). Breastfeeding provides important nutritional and health-related benefits and should be continued to at least 1 year.

Contraindications to Breastfeeding

Contraindications to Breastfeeding

• Herpetic lesions on the mother’s nipples, areolas, or breast

• Maternal diagnosis and treatment of cancer

• Maternal human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, except in some areas (see WHO recommendations [Box 11-1]; breastfeeding for HIV-infected mothers is not recommended in developed countries)

BOX 11-1 World Health Organization Recommendations for Breastfeeding With Human Immunodeficiency Virus

• Acceptable (socially welcome)

• Feasible (facilities and help are available to prepare formula)

• Affordable (formula can be purchased for 6 months)

• Sustainable (feeding can be sustained for 6 months)

• Safe (formula is prepared with safe water and in hygienic conditions)

Adapted from WHO: 10 facts on breastfeeding, 2009. Available at www.who.int/features/factfiles/breastfeeding/en/index.html (accessed Aug 9, 2010).HIV, Human immunodeficiency virus; WHO, World Health Organization.

Characteristics of Human Milk

Characteristics of Human Milk

Components of Human Milk

The uniqueness of human milk to support the growth and development of the human infant cannot be overestimated. Scientists continue to find new components and to clarify the purposes of known components. More than 200 constituents of milk have been identified (Lawrence and Lawrence, 2005).

Anatomy and Physiology

Anatomy and Physiology

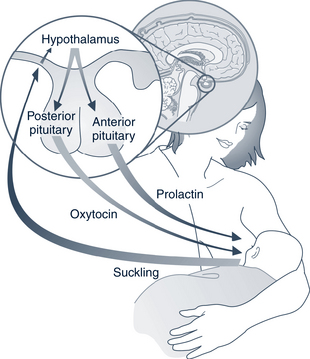

Suckling by the infant is essential to establish and maintain lactation. The amount of milk produced depends on stimulation of the breast, removal of milk from the breast, and release of hormones. The concept of “supply and demand” is an important one for providers and parents to understand. Suckling stimulates the hypothalamus to decrease prolactin-inhibiting factor and permits release of prolactin by the anterior pituitary, which leads to a rise in the level of prolactin. Prolactin levels are directly proportional to the level of suckling by the infant and are more important to initiating than maintaining lactation. The hypothalamus also stimulates the synthesis and release of oxytocin by the posterior pituitary (Fig. 11-1). Oxytocin reacts with receptors in the myoepithelial cells of the milk ducts to initiate a contracting action that results in forcing milk down the ducts. This action increases milk pressure called the letdown reflex or milk ejection reflex. Oxytocin also aids in maternal uterine involution.

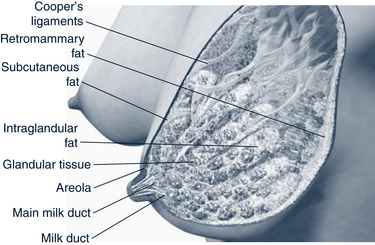

Under the influence of the hormones mentioned previously, the mammary gland undergoes a dramatic change with an increase in size and rapid growth of the lobuloalveolar tissue. The alveoli are the sites of milk production and combine in numbers of 10 to 100 to form lobuli: 20 to 40 lobuli combine into lobes, and 15 to 25 lobes empty into a lactiferous duct. The ducts transport the milk to the nipple (Fig. 11-2).

FIGURE 11-2 Anatomy of the lactating breast.

(Modified from Medela AG, 2006; Ramsay et al: Anatomy of the lactating human breast redefined with ultrasound imaging, J Anatomy, 2005.)

The size, shape, and position of the nipple also vary among women. The nipple may be everted (protuberant from the breast), flat, or inverted. It is not always possible to detect an inverted nipple by observation only. The “pinch test” may be needed to identify nipples that invert with tactile stimulation to the areola. To do the pinch test, place the thumb and forefinger on opposite sides of the areola about 1 to 1.5 inches back from the nipple-areolar junction. Gently compress as though bringing the two fingers together, causing the nipple to become more everted or inverted. This assessment should be conducted prenatally on every patient (Fig. 11-3). Management of inverted nipples is discussed later in this chapter.

Assessment of the Breastfeeding Dyad

Assessment of the Breastfeeding Dyad

Maternal History

Data should be collected about the following areas:

• Overall health, including documentation of any chronic illnesses or allergies

• Previous breastfeeding experience

• Cultural expectations about breastfeeding

• Routine use of over-the-counter, prescribed, or recreational or street drugs, including tobacco, alcohol, and herbal preparations or supplements

• Surgical interventions, especially to the breast or thoracic region

• Family and community support for breastfeeding

• Pregnancy history, especially any complications or need for medications

• Labor and delivery history, including medications, procedures, or complications

Infant History

Data are gathered on the infant in the following areas:

• Congenital conditions, such as cardiac, respiratory, or orofacial conditions

• Trauma or complications during delivery

• Medications received during labor and delivery or in the early postpartum period

• Activities or procedures including circumcision, use of bilirubin lights, or use of bottle, cup, or tube feeding

Maternal Examination

Examination of the mother should focus on an evaluation of the breast in the following areas:

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree