CHAPTER 10 Breast Cancer

For the majority of women with breast cancer, complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) has become a standard part of their treatment and healing.1

THE BREASTS AND THE BREAST EXAM

ANATOMY OF THE BREASTS

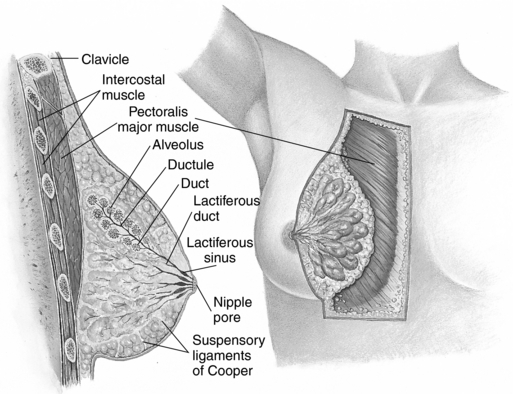

The breasts of an adult woman are tear-shaped mammary glands (Fig. 10-1), technically developmentally modified sweat glands with the potential for milk production. A layer of subcutaneous adipose tissue surrounds the glands and extends throughout the breast itself, comprising 80% to 85% of the normal breast. The breasts are supported by and attached to the pectoral muscles of the thorax by ligaments. Each breast contains 12 to 25 circularly arranged lobes radiating around the nipple. Each lobe is comprised of numerous lobules containing clusters of alveolar glands that produce milk in a lactating woman. The alveolar glands transport the milk into lactiferous ducts that drain its respective lobe. Each lactiferous duct widens to form an ampulla, and then narrows prior to termination at openings in the nipple. A band of circular smooth muscle surrounds the base of the nipple, whereas longitudinal smooth muscle fibers extend this ring, encircling the lactiferous ducts as they converge toward the nipple. The adipose tissue and configuration of lobes determine the size and shape of the breast.

Figure 10-1 Anatomy of the female breast.

Seidel HM: Mosby’s Guide to Physical Examination, ed 6, St. Louis, 2006, Mosby.

The darker-pigmented area around the nipple is called the areola. Its size and color varies from 2 to 6 cm in diameter and from pale pink to deep brown depending on age, parity, and skin pigmentation. The areola contains numerous small oil-producing glands called Montgomery’s tubercles, which serve to lubricate the areola and become more pronounced during pregnancy.3

Women’s breast shape, size, and “tone” are as highly variable as are women themselves. Yet, because of a narrow range of acceptable breast appearance in Western culture, many women are dissatisfied with their breasts. According to the American Society for Plastic Surgery, nearly 250,000 breast augmentation procedures were performed in 2005. Breast augmentation for teenagers accounted for 3841 procedures in 2003. The number of breast augmentations increased 7% from 2002 to 2003. When physicians were asked the primary reason, their patients offered for wanting a breast augmentation, 91% said it was to improve the way they feel about themselves.4

CYCLIC INFLUENCES ON BREAST TISSUE

During pregnancy, in response to progesterone, breast size and turgidity increase significantly, accompanied by deepening nipple and areolar pigmentation, nipple enlargement, areolar widening, and an increase in the number and size of Montgomery’s tubercles. In response to hormonal signals, the alveoli enlarge and their lining cells, the acini cells, increase in number and size (hyperplasia and hypertrophy). The breast ductal system branches markedly. In late pregnancy, the fatty tissues of the breasts are almost completely replaced by cellular breast parenchyma. Secretion of colostrum may begin during pregnancy. After birth, the fully mature breasts secrete milk in response to prolactin.

BREAST CANCER

Breast cancer is perhaps the single most important medical concern women face today. Although there has been an overall decrease in breast caner rates in the United States in recent decades, in 2007 there were greater than 180,000 new cases of invasive breast cancer and 40,910 breast cancer-related deaths. This is equivalent to a breast cancer diagnosis every 2 minutes.2 Breast cancer is the leading cause of cancer in women, accounting for one-third of all cancer cases.3 All women are affected by breast cancer—whether by literal diagnosis or a lifetime of worry about whether they will experience this disease.2 It has been estimated that 50% of all women in the United States at some point in their lives will ask their physicians about a concerning lump or other worrisome breast finding with the anxiety that they have breast cancer. Many have known a friend, relative, or colleague who has gone through a possible or actual breast cancer diagnosis.

RISK FACTORS FOR DEVELOPING BREAST CANCER

Breast cancer is the result of the complex interaction of multiple factors—hormonal, genetic, environmental, and lifestyle.2 Breast cancer risk factors can be divided into nonmodifiable and modifiable risks. The former are heritable or genetic, although it is arguable that genetics can be favorably or negatively influenced by either beneficial or harmful environmental exposures, diet, and therapies that target genetic processes such as transcription and tumor suppression, and thus to some extent, may be modifiable. Modifiable factors include diet, obesity, alcohol intake, and environmental exposures.

GENETICS

Germ line mutations are responsible for no greater than 10% of human breast cancers.3 However, women with specific mutations have a much higher lifetime risk of developing breast cancer, are more likely to experience breast cancer at an earlier age than the average population, and may experience more severe forms of the disease, BRCA-1 and BRCA-2 are known as tumor suppressor genes. Women who have inherited a mutated BRCA-1 allele from either parent have a 60% to 85% lifetime likelihood of developing breast cancer (as well as a 33% chance of developing ovarian cancer). Women with this gene born after 1940 have an even higher risk, attributed to increased exposure to cancer-promoting environmental factors, and Ashkenazi Jewish women have an increased likelihood of carrying this mutation.3 Mutation of the p53 tumor suppressor gene, such as occurs in the inherited Li-Fraumeni syndrome, is associated with an increased incidence of breast cancer and other cancers, as are PTEN tumor suppressor mutations. Heightened oncogene expression is seen in approximately 25% of breast cancer cases. Erb-2 (HER-2 neu), a member of the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) superfamily, is a product of oncogene overexpression, and can contribute to malignant transformation of human breast epithelium.3 Women with a genetic cancer predisposition are considered high risk for breast cancer and may receive recommendations for prophylactic cancer treatment including oophorectomy, elective mastectomy, and chemotherapy with tamoxifen, raloxifene, and/or aromatase inhibitors, discussed in the following.2

Endogenous Hormone Exposure

Breast cancer is a hormone-dependent disease manifesting as a malignant proliferation of clonal epithelial cells lining the ducts or lobules of the breast.3 Its hormonal dependence is demonstrated by the fact that women who lack functioning ovaries and who never received hormone replacement (HR) do not develop breast cancer. Women are 150 times more likely to develop breast cancer than are men because of their greater exposure to estrogen and progesterone.3 Although women may develop breast cancer at any age, there is a slight decline in breast cancer incidence after menopause accompanying naturally declining levels of estrogen and progesterone; however, statistically, as women age they have an increasing likelihood of being diagnosed with breast cancer, likely as a result of a lifetime of accumulated exposures (0.4% chance of diagnosis between 30 and 40 years of age; 4% chance between the ages of 70 and 80 years).3,4

Three life cycle events appear to significantly influence a woman’s overall risk of developing breast cancer: age at menarche, age at first pregnancy, and age at menopause. Women who begin to menstruate at age 16 have 50% to 60% of the risk of developing breast cancer compared with those who experience menarche at age 12.3 Having a full-term pregnancy by age 18 confers a 30% to 40% lower risk of developing breast caner compared with women who have no children, and menopause (natural or surgical) that occurs 10 years prior to the median age of 52 years old for menopause decreases lifetime breast cancer risk by approximately 35%.3 Breastfeeding duration has been shown by meta-analysis to also confer substantial protection against breast cancer regardless of age at first pregnancy or number of pregnancies.3 The risk reduction is directly correlated with a decreased amount of time during which breast tissue is exposed to endogenous estrogens. International variation in breast cancer rates has also supported the role of hormonal exposure as an etiologic factor in breast cancer. Asian women, for example, have been found to have significantly lower serum estrogen and progesterone levels, and have breast cancer rates of 10% to 20% of women in westernized nations (see discussion on diet and phytoestrogens).

Alcohol Intake

Even modest amounts of regular alcohol consumption (e.g., one glass of wine daily) has been associated with a 26% increased risk of breast cancer on the basis of multiple cohort studies.2,3 Folic acid supplementation may modify this risk somewhat.3 The risk of breast cancer needs to be weighed against the cardioprotective effects of modest alcohol intake.3

Dietary Fat Intake and Obesity

Dietary fat intake has been a focus of much research and debate. The dietary fat hypothesis, which proposed a correlation between amount of dietary fat intake and breast cancer incidence, is based on the observation that national per capita fat consumption is highly correlated with breast cancer mortality rates. However, per capita fat intake is also associated with economic prosperity, and this is accompanied by other factors that are also related to breast cancer risk, such as early menarche, low parity, later age at first birth, and lower levels of physical exercise.5 Studies have failed to show a direct correlation between consumption of specific types of dietary fats, or the amount of fat in the diet, and breast cancer.6 However, excessive caloric intake from any source in adolescent girls has been shown to lead to earlier menarche, whereas in older women can delay the onset of menopause, which as discussed are risk factors for breast cancer development.3

Obesity has been correlated with increased risk of all-cause mortality in women.7 Postmenopausal weight gain and obesity have been shown to increase breast cancer risk by as much as 50%.2 Increased risk results from prolonged and increased aromatase activity in the adipose tissue leading to increased conversion of fat to estrogen.2,3,7 As many as 20% of all postmenopausal breast cancers and 27% of all cancers in women over 70 years of age may be attributable to obesity or moderate to significant weight gain after the fifth decade of life, and up to 50% of all postmenopausal deaths resulting from breast cancer may be attributable to obesity.7 Obesity is also a risk factor for poor breast cancer prognosis with larger tumor size, greater risk of metastases, poorer surgical outcome, and less efficient response to chemotherapy and radiation. The Cancer Prevention Study II concluded that as many as 18,000 deaths of women in the United States over 50 years old could be prevented if women maintained a body mass index (BMI) of less than 25 kg/m2 throughout adulthood.7 Weight loss and maintenance of weight in the BMI ranger of 19 to 25 kg/m2 has been shown to reduce breast cancer risk by about 30%.2

Environmental Hormone Exposure

Exogenous hormone exposure may play a significant risk in the etiology of breast cancer. There is well-supported evidence that many commonly used chemicals and widespread environmental pollutants act as hormone disruptors.8 Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) and polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), in conjunction with certain genetic polymorphisms involved in carcinogen activation and steroid hormone metabolism, cause mammary gland tumors in animals specifically by mimicking estrogen, or increasing susceptibility of the mammary gland to carcinogenesis.9 Evidence regarding dioxins and organic solvents is sparse and methodologically limited but also suggestive of an association between breast cancer and exposure.9 Scientist Rachel Carson suggested the role of environmental contamination in human cancers several decades ago, however, it is only in recent years that the role of exogenous hormones acting as hormone disruptors has begun to be seriously studied, and a great deal is unknown.

Although older studies suggested an association between oral contraceptive (OC) use and breast cancer, more recent meta-analyses imply little to no breast cancer risk from their use.2,3 The Women’s Health Initiative trial found a correlation between risk of breast cancer (and increased cardiovascular risk) and hormone replacement therapy (HRT), particularly with conjugated equine estrogens (CEE) plus progestins. Further, women with a prior breast cancer diagnosis have an increased rate of recurrence with HRT.3 Minimizing unnecessary human exposure to known endocrine disruptors and other carcinogens should be high on our national medical and environmental research budgets.

Prior Radiation Exposure

Women with Hodgkin’s lymphoma who were treated with thoracic radiation have a significantly higher risk of developing breast cancer caused by exposure.2

Lifetime vs. Age-Adjusted Risk of Developing Breast Cancer

The figure that one in eight women will develop breast cancer is slightly misleading and may create unnecessary fear in women. Based on statistics from 2002 to 2003 from the National Cancer Institute (NCI), 12.7% will be diagnosed with cancer in their lives, and it is from this figure that the “one in eight” statistic is derived. However, lifetime risk is a cumulative average and does not reflect a woman’s risk at different ages. The age-adjusted risk gives women a more realistic, although still generalized, picture of their risk of developing breast cancer. According to the NCI’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results statistics (http://seer.cancer.gov/), a woman’s chance of being diagnosed with breast cancer is:

Of course, as discussed, many more factors than gender, age, and nationality contribute to breast cancer risk. To adjust for such factors as genetics, weight, and lifestyle, a number of statistical tools have been devised to calculate what might be closer to actual risk for any individual woman. The most widely used scale is the Gail model, which is available as a risk calculator via the National Cancer Institute website at http://www.cancer.gov/bcrisktool/for individuals and practitioners to use.2,10,11 The tool is not a valid method of calculating breast cancer or recurrence risk in women who have already had a diagnosis of breast cancer, lobular carcinoma in situ (LCIS), or ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS). One research group suggests that another model, the Rosner and Coldiz model, more accurately classifies women according to their risk stratification; however, it is not as widely used as the Gail model.11

Race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status have been associated with delayed diagnosis of breast cancer, and therefore may contribute to poorer outcomes. Breast cancer outcomes are also worse for uninsured and Medicaid patients than for privately insured patients.12

Breast Cancer in Pregnancy

During pregnancy breast tissue is stimulated by increased levels of estrogen, progesterone, prolactin, and human placental lactogen (HPL).3 Breast cancer occurs at a rate of 1/3000 to 4000 pregnancies. Pregnant or lactating women should have any persistent breast or axillary lumps evaluated by a gynecologist. Too often breast lumps in this population are dismissed by women or health care professionals as the result of hormonal changes, unfortunately sometimes leading to detection of breast cancer only once it has become advanced.

CONVENTIONAL RISK REDUCTION STRATEGIES

Conventional breast cancer risk reduction strategies include:2

Surveillance

Breast Self-Exam

A recent review by the Cochrane group, the results of several large randomized trials, and a review by the US Preventative Services Task Force (USPSTF) all concluded that breast self-exam (BSE) does not reduce breast cancer specific mortality, and in fact, may increase the number of unnecessary biopsies women receive for benign findings.4 Nonetheless, it is a noninvasive method that some women find self-empowering or reassuring to perform, and which may sometimes lead to the early detection of breast cancer.3 Women should be informed about the potential risk of BSE findings leading to unnecessarily invasive testing and they should be taught to perform the BSE correctly to maximize the value of the exam.

Breast cancer is a leading cause of death in American women. Overall exposure to circulating and environmental estrogens, lifestyle factors, and genetic predisposition may all contribute to breast cancer development. The clinical practitioner should include a thorough breast exam as part of routine gynecologic care. It is a simple technique, and when done properly, can be an important part of overall cancer screening. In recent years, the value of the BSE has come under scrutiny, and large trials suggest that it is not helpful in reducing cancer mortality and may actually contribute to an overall higher rate of unnecessary breast biopsies. It is clear that if women wish to perform BSE, they should be taught to do so correctly. The Susan E. Komen Breast Cancer Foundation website (http://www.komen.org/bse/) offers a valuable video demonstration on the proper techniques for BSE, relevant to the health practitioner and patient alike. Additionally, numerous other websites provide invaluable resources on BSE for patients and care providers. The following discussion provides very general guidelines for BSE.

When to Perform a Breast Self-Exam

In 80% of all cases, breast lumps and changes do not signal breast cancer. However, women should report all unusual changes (Box 10-1) to their health care provider and seek a clinical evaluation. Many women put off telling their doctor out of fear. It can be reassuring for patients to know that at least 50% of all women will seek evaluation for a suspicious lump or breast change at some point in their life.

BOX 10-1 Breast Self-Exam

Breast Changes and Warning Signs

Differentiating Breast Lumps by Palpation

WARNING: A physician should evaluate persistent lumps or abnormalities as soon as possible.

Performing the Breast Self-Exam

Breast self-examination requires examining the entire chest area and both breasts, as well as the axillary area. Although it does not matter in what order the steps of the BSE are performed, it is essential that all steps be performed so that no area remains overlooked. Therefore, women should perform the BSE systematically each time. A log or journal, with an entry after each exam, can help a woman keep track of her findings, and can help her to objectively track any changes she might notice. The instructions that follow are adapted from the American Cancer Society.

General Rules

Although cancerous growths are most likely to be found in the upper, outer breast quadrant or behind the nipple, they can occur in any area of the breast, chest, or lymph network (Box 10-2); therefore, a thorough exam is essential.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree