12.2 Bone and joint infections

Pathogenesis

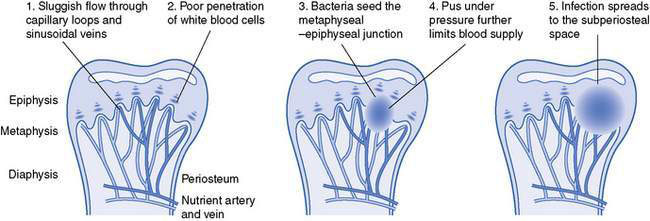

The area around the growth plates of children’s bones is particularly prone to infection. Although the metaphysis has a plentiful blood supply from nutrient arteries, blood flow through capillary loops and sinusoidal veins at the metaphyseal–epiphyseal junction is slow, which allows bloodborne bacteria to deposit in this region (Fig. 12.2.1). This area also has poor penetration of white blood cells and other immune mediators, so deposited bacteria are relatively protected. As the infection progresses, pus accumulates under pressure, further limiting the blood supply to the region. Increased stasis and activity of cytokines encourages clots to form in blood vessels, leading to ischaemic bone necrosis. Infection then spreads to the cortex through the Volkmann canals and haversian system, and subsequently into the subperiosteal space.

Fig. 12.2.1 Anatomical evolution of osteomyelitis.

(Adapted with permission from Krogstad P, Smith AL 2004 Osteomyelitis and septic arthritis. In: Feigin RD, Cherry JD, Demmler GJ, Kaplan SL (eds) Textbook of pediatric infectious diseases, 5th edn. WB Saunders, Philadelphia, PA, pp 683–703.)

Microbiology

• Staphylococcus aureus (80–90% of culture positive cases) – usually methicillin-susceptible but community-acquired methicillin-resistant S. aureus (CA-MRSA) is on the rise in many places.

• Kingella kingae – recent studies using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) diagnosis suggest that this organism is a common cause of osteomyelitis and septic arthritis in young children (usually under 2 years), but is often not identified using standard laboratory cultures.

• Streptococcus pyogenes (group A streptococcus) – sometimes associated with varicella infection.

• Streptococcus pneumoniae – mainly in children aged less than 2 years.

• Pseudomonas aeruginosa – immunocompromised patients or traumatic (classical cause is a nail through a tennis shoe causing calcaneal osteomyelitis).

• Group B streptococcus or Escherichia coli – especially in neonates.

• Haemophilus influenzae type b – in unimmunized populations (mainly in developing countries).

• Mycobacterium tuberculosis – mainly in children from developing countries or immigrant populations; 50% of cases affect the spine. Often subacute presentation.

• Salmonella spp – particularly in people with sickle cell anaemia.

• Neisseria gonorrhoeae – mainly in developing countries; may cause multifocal septic arthritis in neonates or sexually active adolescents.

Clinical presentation

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree