There is a greater risk of dying on the first day of life than on any other day (except the last).

There is a greater risk of dying on the first day of life than on any other day (except the last).7.1 The effects of birth on the fetus

7.1.1 Normal physiology (Table 7.1)

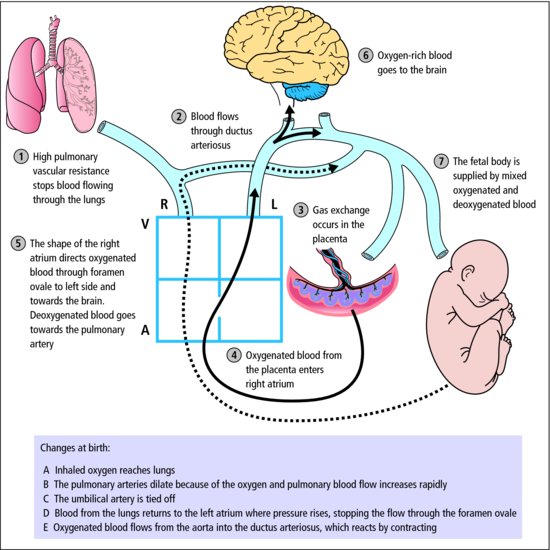

The most dramatic events are the switch from placenta to lung as the organ of gas exchange, and the change from fetal to adult circulation (Figure 7.1).

Table 7.1 Normal physiological events at birth

| Phenomena | Effects |

Stress of labour  catecholamine and steroid catecholamine and steroid | ↓ Lung liquid and ↑ surfactant release |

| Compression of thorax in birth canal | Expulsion of lung liquid |

| Sensory stimuli and clamping of umbilical cord | Initiation of breathing |

Air enters lungs  ↑ lung tissue oxygen ↑ lung tissue oxygen | Pulmonary vascular resistance ↓  ↑ pulmonary blood flow ↑ arterial Po2 ↑ pulmonary blood flow ↑ arterial Po2 |

| Systemic pressure > pulmonary pressure | Foramen ovale closes |

| Ductus arteriosus fills with oxygen-rich blood | Ductus arteriosus closes |

Figure 7.1 Fetal circulation. Follow the circulation in the fetus 1 to 7. Then review the changes which occur at birth, which are listed A to E at the bottom of the figure.

For most fetuses these events occur without problems; a minority suffer potentially damaging asphyxia along the way.

7.2 Perinatal asphyxia and its prevention

In the healthy fetus the Po2 is only about 4 kPa, which is the arterial Po2 at the summit of Mount Everest (normal child 12–15 kPa). The needs of the fetus are fully met thanks to fetal adaptation, but oxygenation around the time of birth is in a state of delicate balance which depends critically on many factors.

Fetal adaptations to hypoxia

Fetal adaptations to hypoxia- High haemoglobin (18 g/dL)

- Fetal haemoglobin with left shifted dissociation curve (Chapter 25)

- High cardiac output.

It is not surprising that the fetus has good defences against acute hypoxia. These include redistribution of blood flow in favour of vital tissues, and a myocardium and nervous system more resistant to hypoxic damage than those of the adult. Despite this, a small minority of fetuses suffer perinatal brain damage. Fetal hypoxia calls for prompt obstetric action and resuscitation at birth in order to prevent permanent damage.

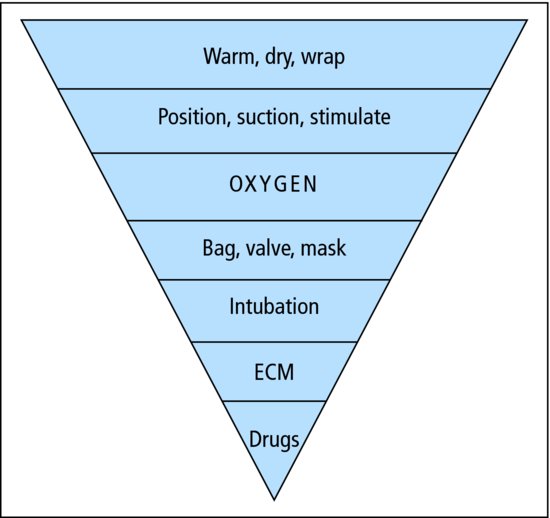

7.2.1 Resuscitation (Figure 7.2)

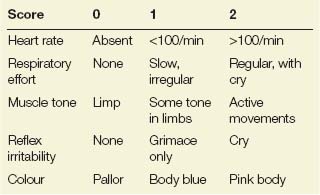

Rapid assessment and action is needed for any baby who does not breathe within 30 s of birth, or who exhibits slow or irregular gasping. Bradycardia indicates hypoxia (Tables 7.2 and 7.3).

Figure 7.2 Resuscitation of the newborn. If you are at a delivery, rapidly assess pulse, respiration and colour. All babies are cleaned, dried and wrapped. If assessment is not satisfactory, move down the steps of the triangle, re-assess frequently, and go back up the triangle as the baby improves. External cardiac massage (ECM) and drugs are not used very often. You will need special training when you work with newborns.

Table 7.2 Apgar score, usually recorded at 1, 5 and 10 min after birth

Table 7.3 Pointers to fetal hypoxia

| Obstetric | Fetal |

| Antepartum | |

| Placental disease (pre-eclampsia, diabetes) | Intrauterine growth retardation |

| Placental abruption | Reduced fetal movements |

| Severe maternal illness | Abnormal fetal blood flow (Doppler’s) |

| Intrapartum | |

| Umbilical cord prolapse/compression | Meconium-stained liquor |

| Obstructed labour/shoulder dystocia | Abnormal fetal heart rate (cardiotocograph) |

| Placenta praevia/placental abruption | Metabolic acidosis (fetal blood sample) |

| Postpartum | |

|

Avoid hypothermia by drying, and use the radiant heater (Figure 7.3). If needed, clear secretions from the mouth and then the nose with a soft suction catheter. In the correct position, the neck is extended, allowing for the infant’s large occiput. If hypoxia is not far advanced, breathing can usually be started by stimulation: gentle rubbing with a towel dries and stimulates! Some asphyxiated infants are pale, limp, apnoeic and bradycardic, and intermittent positive pressure ventilation is begun by either bag and mask or tracheal tube.

Figure 7.3 The resuscitaire comprises a heater, source of oxygen and suction, and an equipped platform for neonatal resuscitation.

PRACTICE POINT

PRACTICE POINTInfants who recover rapidly should be given to their mothers as soon as possible. Some babies with severe asphyxia need to be admitted to the neonatal unit.

7.2.2 Birth asphyxia

Birth asphyxia is the consequence of intrapartum fetal hypoxia/ischaemia. Most infants will recover rapidly with prompt resuscitation. More severe asphyxia may lead to hypoxic ischaemic encephalopathy (HIE), the acute neurological illness due to the effects of asphyxia on the fetal brain. HIE occurs in 1–2 per 1000 deliveries.

TREATMENT

TREATMENTHIE is graded by clinical severity in the first days. The grade is important for prognosis (Table 7.4).

Table 7.4 Hypoxic ischaemic encephalopathy (HIE) grading

| HIE grade | Prognosis |

| Mild: irritable with a high-pitched cry and poor feeding | Normal |

| Moderate: lethargic and hypotonic, poor feeding and occasional fits | 40% risk of cerebral palsy |

| Severe: diminished conscious level, no spontaneous movement, multiple seizures and multi-organ failure | 30% mortality 90% cerebral palsy |

HIE requires intensive care. Some 20% of cerebral palsy is due to intrapartum hypoxic-ischaemic damage.

7.3 Routine care of the normal baby

Labelling. All newborn babies should have name bands attached to wrist and ankle in the delivery room and in the presence of the mother.

Vitamin K. Newborn babies have low levels of vitamin K and its dependent clotting factors. Untreated, in less than 1%, this causes haemorrhagic disease of the newborn with bleeding from the gastrointestinal tract, into the skin or mucous membranes, or rarely into the brain. Haemorrhagic disease is prevented by prophylaxis.