CHAPTER 23 Biliary Atresia

Step 1: Surgical Anatomy

♦ Biliary atresia is thought to be the result of an inflammatory process that destroys the bile ducts, causing fibrous obliteration of the intrahepatic and extrahepatic bile ducts and consequent biliary cirrhosis.

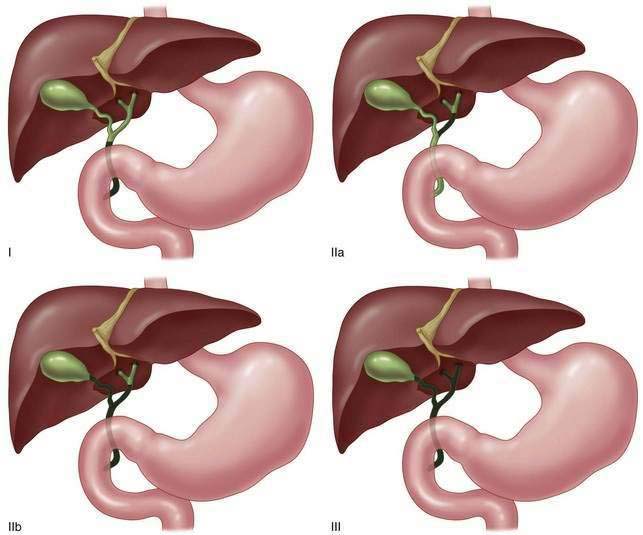

♦ Biliary atresia has been classified by subtype based on macroscopic and cholangiographic findings (Fig. 23-1):

♦ These subtypes allow for comparison of common groups and are based on extrahepatic ductal involvement. The degree of intrahepatic involvement associated with the type III lesion is a key contributor to the prognosis for successful reconstruction and the duration of response.

Step 2: Preoperative Considerations

♦ The cardinal signs and symptoms are jaundice within weeks after birth and the development of acholic stools, dark urine, and hepatomegaly. Any newborn with persistent jaundice after 4 weeks of age should be aggressively investigated. The clinical examination is typically normal in early presentations, and an enlarged liver is often appreciated by 6 to 8 weeks of age.

♦ Laboratory examination demonstrating direct (conjugated) hyperbilirubinemia is the hallmark of biliary atresia. This should never be confused with physiologic jaundice of the newborn, which shows indirect (unconjugated) hyperbilirubinemia. Because the cause of pathologic jaundice in an infant is diverse, biochemical evaluation must include hepatitis serologies, TORCH (toxoplasmosis, rubella, cytomegalovirus, and herpes simplex) titers, α1-antitrypsin level, serum ferritin, and a sweat chloride test or direct genetic analysis to rule out cystic fibrosis.

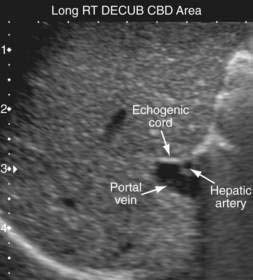

♦ Abdominal ultrasound is useful in the evaluation of cholestatic jaundice. Absence of the gallbladder or identification of a small, shrunken, noncontractile gallbladder is suggestive of biliary atresia. Occasionally the fibrous cord remnant of the biliary ducts can be identified as the “triangular cord” sign (Fig. 23-2, portal vein and hepatic artery with echogenic cord in expected region of bile duct).

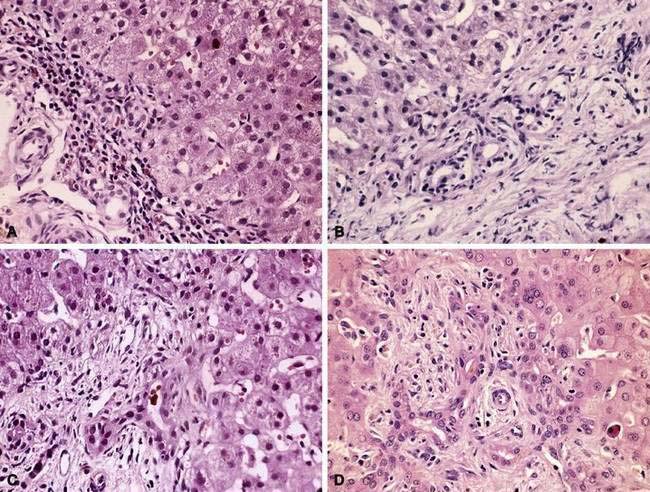

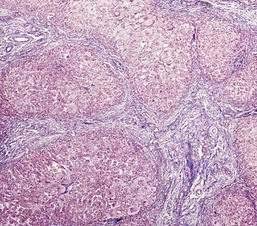

♦ Liver biopsy is considered the most reliable preoperative test in the diagnosis of biliary atresia. Histologic findings consistent with biliary atresia include preservation of basic hepatic architecture (Fig. 23-3, A); bile ductular proliferation (Fig. 23-3, B); bile duct plugs (Fig. 23-3, C); inflammatory cell infiltrate, hepatocyte giant cell transformation, and edema and fibrosis of the portal tract (Fig. 23-3, D). Uncorrected biliary atresia results in histologic evidence of cirrhosis as early as 3 to 4 months of age (Fig. 23-4).

Step 3: Operative Steps

Anesthetic Induction

♦ General endotracheal anesthesia is administered by standard technique. A urinary catheter and a nasogastric tube are placed.

Incision

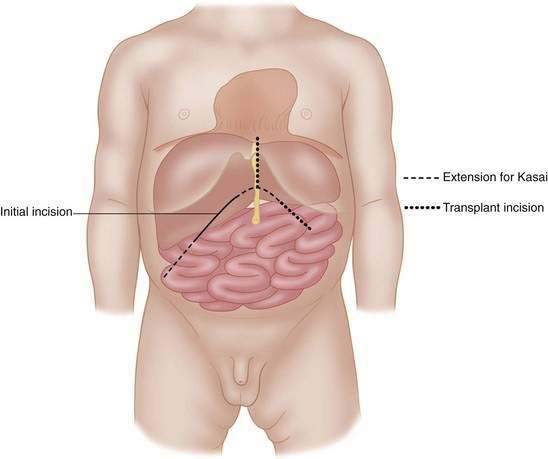

♦ A short subcostal incision (Fig. 23-5, solid line) overlying the gallbladder region of the liver will allow initial investigation and cholangiography. If the diagnostic phase of the operation confirms biliary atresia, we prefer to extend this incision to a full subcostal incision to allow for mobilization of the liver.

♦ The suspensory ligaments of the liver, the coronary and falciform ligaments, are divided to mobilize the liver in the abdomen. The liver is then externalized and rotated to allow clear and unobstructed observation of the hilum and the vascular structures. We find that this exposure facilitates safe dissection of the lateral fibrous mass regions, and it does not significantly complicate liver transplantation if needed in the future.

♦ The operation is divided into two stages: (1) diagnostic confirmation and (2) Kasai portoenterostomy.

Operative Procedure Step 1: Diagnostic Confirmation

♦ The liver in biliary atresia is characteristically firm, dark, and cholestatic in color, and it typically has many subcapsular telangiectatic vessels on its surface, representing early cirrhosis and portal hypertension changes (Fig. 23-6). Metabolic liver diseases rarely demonstrate these features.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree