CHAPTER 46 Benign disease of the breast

Stages of Human Breast Development

The lifecycle of the breast involves three main stages: development (and early reproductive life), mature reproductive life and involution. The mammary buds develop during the sixth week as outgrowths of epidermis into the underlying mesenchyme. These mammary buds develop as downgrowths from mammary crests, which are thickened strips of ectoderm extending from the axilla to the inguinal region. During the fourth week, the mammary crests appear and persist in humans in the pectoral region where the breasts develop (Sandler 2006). Several mammary buds developing from each primary bud eventually form lactiferous ducts, and by gestation 15–20 lactiferous ducts are formed. The adipose tissue and fibrous connective tissue of the breast develop from the surrounding mesenchyme. In the late fetal period, the epidermis at the origin of the mammary gland forms a shallow mammary pit, from which the nipples arise soon after birth due to epithelial proliferation of the surrounding connective tissue of the areola. At birth, the mammary glands of males and females are identical, enlarged and, on occasion, may produce a secretion called ‘witch’s milk’. The mammary gland remains undeveloped until puberty, with only the main lactiferous duct formed.

Breast development proceeds identically in boys and girls until puberty. During puberty, the female breast enlarges rapidly. The elevated level of circulating oestrogens causes growth of the ductal system; however, progesterones, growth hormone, prolactin and corticoids also play a role. During pregnancy, an increase in the number of lobules and a loss of fat occurs due to raised oestrogen levels and a sustained increase in the level of progesterone. The intralobular ducts form buds that become acini; the lactating breast is composed of dilated acini that contain milk. During weaning, following the suckling stimulus, the breast involutes and the secretory cells are removed by apoptosis and phagocytosis (Howard and Gusterson 2000). The two-layer epithelium of the breast is reformed following weaning. Following successive pregnancies and periods of involution, the terminal duct lobular units (the functional unit of the breast) increase and decrease in size, with an increase and decrease in the number of acini. During involution, the breast stroma is replaced by fat and, as a result, the breast becomes less radiodense, softer and more ptotic (Dixon 1994).

Congenital Abnormalities

These disorders are not uncommon referrals at breast clinics and can cause considerable concern.

Accessory breast tissue and supernumerary nipples

Accessory breast tissue consists of ectopic breast tissue resulting from the failure of the embryonic mammary ridge to regress, commonly found in the anterior axillary line (Qian et al 2008). This occurs in 0.4–0.6% of the population, although is more common in Asian women, and is bilateral in one-third of cases. Accessory breast tissue can cause discomfort, cosmetic problems and restriction in arm movement. This breast tissue may become prominent during pregnancy, and both benign and malignant conditions may occur within this tissue. An explanation of the ‘abnormality’ and reassurance is often all that is required, and surgical excision should be reserved for symptomatic patients as a good cosmetic outcome is difficult and associated with significant morbidity.

Breast hypoplasia and Poland syndrome

Poland syndrome is a group of conditions in which amastia develops with varying degrees of absence of the pectoralis muscles and syndactyly, affecting one in 30,000 live births (Figure 46.1). It was first described by Alfred Poland in 1841, whilst he was a medical student at Guys Hospital, London (Ram and Chung 2009). Subsequent reports have added numerous additional components to the syndrome including mammary hypoplasia, costal cartilage defects and rib defects. One study evaluating 75 patients showed 100% with an absence or hypoplasia of the pectoralis major, 67% with a hand abnormality, and 49% with athelia (congenital absence of one or both nipples) and/or amastia (breast tissue, nipple and areola is absent; differs from amazia which only involves the absence of breast tissue, and the nipple and areola remain present) (Katz et al 2001). The syndrome is almost always unilateral, with the right side more often affected than the left side, and is more common in men than women (3:1). Patients with Poland syndrome often request reconstruction of the muscular defect, producing symmetry and improving psychological well-being. This can be performed with an ipsilateral latissimus dorsi pedicled flap with or without an implant.

Aberrations of Normal Development and Involution

Fibroadenoma

Simple fibroadenoma

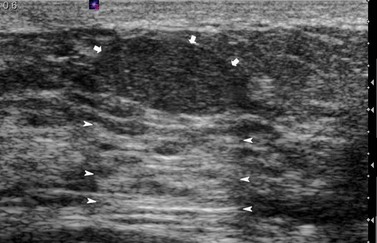

These are discrete, firm, highly mobile, benign breast masses which may present symptomatically or as an incidental screening finding. Fibroadenomas usually present unilaterally; however, in 20% of cases, multiple lesions may present in the same breast or bilaterally. They are found most commonly at the time of greatest lobular development in women aged 15–35 years. The encapsulation explains the motility of the masses, making them appear more superficial than they truly are (Figure 46.2). Fibroadenomas develop from the special stroma of the lobule. They are hormone dependent, lactate during pregnancy and involute with the rest of the breast in the perimenopause (Hughes et al 1987). A direct association has been reported between use of the oral contraceptive pill before the age of 20 years and risk of fibroadenoma. The Epstein–Barr virus is thought to play a causative role in the development of this tumour in immunosuppressed patients (Kleer et al 2002). Observation of fibroadenomas in younger women showed that 55% do not change size, 37% get smaller and 8% increase in size. Fifty percent of fibroadenomas contain other proliferative changes such as adenosis, sclerosing adenosis and duct epithelial hyperplasia; these are known as ‘complex fibroadenomas’. Complex fibroadenomas, but not simple fibroadenomas, are associated with an increased risk of breast cancer (Carter et al 2001). Fibroadenomas in older women or in women with a family history of breast cancer have a higher risk of associated breast cancer (Dupont et al 1994, Shabtai et al 2001).

Fibroadenomas over 5 cm in size are known as ‘giant fibroadenomas’, and are seen more commonly in women of African origin. Cancers rarely appear within a fibroadenoma. Patients with a histologically confirmed fibroadenoma can be managed conservatively, with follow-up imaging at 6 months to confirm that the lesion is not increasing in size. Excision is recommended if the mass increases in size, if it is larger than 3–4 cm or at the patient’s request. Recurrence is rarely due to incomplete excision, and is often due to an undiagnosed adjacent mass. A minimally invasive technique, such as ultrasound-guided cryoablation, is a treatment option for fibroadenomas in women who do not wish to have surgery (Caleffi et al 2004). Rapid growth of a fibroadenoma can occur in adolescence (juvenile fibroadenoma) or in women of perimenopausal age. Juvenile fibroadenomas usually present as painless, solitary unilateral masses over 5 cm in size (reaching up to 15–20 cm). Although benign, surgical excision of these masses is advised (Wechselberger et al 2002).

Phyllodes tumour

Johannes Muller (1838) first described a large mammary tumour with a cystic appearance and leaf-like growth pattern; he named this ‘cystosarcoma phyllodes’. Treves and Sunderland (1951) proposed that benign, premalignant and malignant forms of this disease existed. The term ‘phyllodes tumour’ (PT) was adopted by the World Health Organization in 1981 to describe this rare fibroepithelial lesion, which accounts for less than 1% of all breast neoplasms. They are less common than fibroadenomas (ratio 1:40), from which they need to be distinguished. PTs can present in women of any age, including adolescents and the elderly, but the majority occur in women aged 35–55 years; the median age of presentation is 45 years. PTs present clinically as a well-circumscribed, mobile mass which may be growing rapidly. The size of presentation of PTs is larger than that for fibroadenomas, although with increased breast awareness and the advent of breast screening, there has been a trend towards smaller tumours. Other signs and symptoms include dilated skin veins, blue skin discolouration, nipple retraction, fixation to the skin or pectoralis muscle, and pressure necrosis of the skin. Palpable axillary lymphadenopathy has been identified in up to 20% of patients, but axillary metastatic involvement is rare. PTs are more commonly found in the upper outer quadrant of the breast. Prevalence is higher in Latin American White and Asian populations. Certain clinical features may raise the index of suspicion, including a sudden increase in a longstanding breast mass, a fibroadenoma over 3 cm in size in a patient aged over 35 years, lobulated appearance on mammography, cystic areas within a solid mass on ultrasonography, and indeterminate features on fine needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) (Jacklin et al 2006). PTs are often not clinically distinguishable from fibroadenomas.

Diagnosis of PTs by FNAC is associated with a high false-positive rate due to the heterogeneity of the tumours. The risk of sampling error is reduced following a core biopsy. Criteria have been formulated to help physicians to select patients for core biopsy — the Paddington Clinicopathologic Suspicion Score (Jacklin et al 2006). Twenty-five percent of PTs are categorized as malignant and more than 50% are categorized as benign, with a number of prognostic factors implicated in the risk of local and distant recurrence including tumour size, grade and margin status. Benign PTs have the potential to recur locally, and rarely present at distant sites. Despite having an increased risk of distant spread (20%), malignant lesions have a 15-year survival rate of 89%.

Nipple Discharge

Ductoscopy allows direct visualization of the discharging duct, and biopsy, by a microendoscope, was investigated by Okazaki in the early 1990s. The procedure is carried out using local anaesthesia (topical local anesthetic cream plus intradermal local anesthetic injection at the areolar margin) and has no significant complications (Escobar et al 2006). An endoscope is inserted through the duct opening on the nipple surface after dilating the duct with a probe (e.g. lacrimal dilator), and saline solution is injected into the duct through the channel to widen it and facilitate the passage of the endoscope, enabling visualization of the intraductal space (Escobar et al 2006). Whilst ductoscopy can be used as a diagnostic and therapeutic addition in patients with nipple discharge, there is no evidence to support its use in the management or early detection of breast cancer.

The aetiology of non-surgically-treated nipple discharge can be grouped into four categories:

Intraductal papilloma and papillomatosis

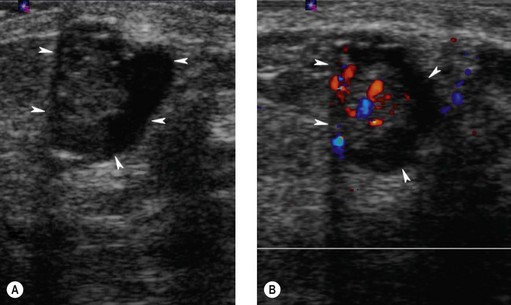

Intraductal papillomas are benign intraductal proliferations, usually found in the major ducts beneath the nipple (lactiferous sinuses); however, they can be found anywhere in the breast. The term ‘papilloma’ describes the fibrovascular cores covered by a double layer of cells comprising an outer myoepithelial layer and an inner luminal cell layer (Mallon et al 2000). The cells are cytologically benign. Squamous and apocrine metaplasia are common findings. There are three types of intraduct papilloma: solitary, multiple or juvenile papillomas. Solitary duct papillomas are the most common; these occur in large ducts (within 5 cm of the nipple) and present with either bloody or a serous single duct discharge (Figure 46.3). Two studies have demonstrated a correlation between the presence of atypical ductal hyperplasia (ADH) in a papillary lesion on needle core biopsy and the presence of invasive or in-situ carcinoma of the breast in the excisional biopsy (Agoff and Lawton 2004, Ivan et al 2004). It has been suggested that the risk of recurrence of papilloma is related to the presence of proliferative breast lesions in the surrounding breast tissue (MacGrogan and Tavassoli 2003). Papillomatosis (multiple intraductal papillomas; 10% of intraductal papilloma) is defined as a minimum of five discrete papillomas within a localized segment of breast tissue. Papillomatosis tends to occur in younger patients and is less often associated with nipple discharge. Multiple papillomas are more frequently peripheral, bilateral, present as a palpable mass and have a higher probability of having an in-situ or invasive carcinoma than central papilloma. Thorough radiological imaging of the contralateral breast is required to exclude malignancy (Ali-Fehmi et al 2003). Multiple papillomas are associated with an increased risk of developing subsequent breast cancer (Krieger and Hiatt 1992, Page et al 1996, Levshin et al 1998). Juvenile papillomatosis is a rare condition defined as severe ductal papillomatosis occurring in women under 30 years of age (median age 20 years). It often presents as a discrete mass up to 8 cm in diameter, and consists of a mixture of cysts, nodules of sclerosing adenosis and complex intraduct proliferations containing myoepithelial cells and luminal cells. Due to the holes seen in the cut surface of the tumour, it has been called ‘Swiss cheese disease’. A number of studies have suggested an association between juvenile papillomatosis and familial breast cancer; therefore, long-term follow-up is advised (Bazzocchi et al 1986).

Mastalgia

The majority of patients can be managed by exclusion of cancer and reassurance. Evening primrose oil (EPO) was previously used in the treatment of mastalgia, but has recently been withdrawn from prescription by the Medicines Control Agency. A recent randomized, double-blind controlled trial of 121 women comparing EPO and fish oil with control oils in the treatment of mastalgia showed no clear benefit from either EPO or fish oils (Blommers et al 2002). This study showed that 33% of women with cyclical mastalgia and 17% of women with non-cyclical mastalgia showed an improvement in symptoms with EPO compared with the control group (46% and 17% improvement, respectively). Other agents have shown some benefit, including phytoestrogens (soya milk) and Vitex agnus-castus (a fruit extract). A reduction in dietary fat intake has also been shown to improve symptoms. Second-line treatments include tamoxifen 10 mg daily and danazol 200 mg daily. Tamoxifen given in the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle controlled mastalgia in 85% of women, with recurrent pain noted in 25% of patients at 1 year. Tamoxifen has been found to be superior to danazol with a better toxicity profile. Fifty-three percent of patients receiving tamoxifen compared with 37% of patients receiving danazol were pain-free after 1 year. It is important to note that tamoxifen is not licenced for use in mastalgia. Due to the high toxicity rate (80%), bromocriptine is no longer used in the treatment of mastalgia.

Fibrocystic Change

Fibrocystic change (FCC; also called fibrocystic disease, cystic mastopathy, chronic cystic disease, mazoplazia, Reculus’s disease) is the most common benign disorder of the breast, affecting women between 20 and 50 years of age (Cole et al 1978, Hutchinson et al 1980, Cook and Rohan 1985, La Vecchia et al 1985, Bartow et al 1987, Sarnelli and Squartini 1991, Fitzgibbons et al 1998). FCC is observed in approximately 50% of women clinically and in 90% histologically (Love et al 1982). The most common symptoms of FCC are breast pain and tender nodularity. FCC is thought to be due to a hormonal imbalance, particularly the predominance of oestrogen over progesterone; however, the pathogenesis is not completely understood (Dupont and Page 1985). FCC is made up of cystic lesions (macrocystic and microcystic) and solid lesions, and includes adenosis, epithelial hyperplasia with or without atypia, apocrine metaplasia, papilloma and radial scar. FCC can be classified into non-proliferative lesions, and proliferative lesions with or without aytpia (atypical hyperplasia) (Dupont and Page 1985).

Non-proliferative lesions are not associated with an increased risk of developing breast cancer; however, women with proliferative disease without atypia and with atypia are at greater risk of breast cancer (relative risk 1.3–1.9 and 3.9–13.0, respectively) (Dupont and Page 1985, Palli et al 1991, Dupont et al 1993, Marshall et al 1997

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree