Baiba J. Grube

Armando E. Giuliano

Benign breast diseases are among the most common diagnoses that the busy obstetrician-gynecologist will see in practice. An ability to accurately and promptly diagnose both benign and malignant breast diseases is within the purview of the practicing gynecologist (1). Benign breast disease is a complex entity with a range of physiologic changes and clinical manifestations that have an impact on a woman’s health independent of breast cancer risk (2).

Detection

History

Evaluation of a new breast symptom begins with assessment of symptoms based on a thorough clinical history (3). The history should include questions regarding current symptoms, duration of the condition, fluctuation of the signs and symptoms, and factors that aggravate or relieve the symptom. Assessment of breast problems should focus on the following points:

The patient should be questioned about the following risk factors for breast cancer (see Chapter 40 for more details):

Breast cancer risk can be determined by the Gail Risk assessment model, which is available electronically (4). The Gail Risk assessment model calculates risk based on patient race, age, age of menarche, age of first live birth, number of first-degree relatives with breast cancer, number of previous breast biopsies, and presence of atypia on the biopsy.

It is important to obtain a current list of medications used, including hormone therapy and herbal medications such as phytoestrogens. The gestational history should take into consideration the possibility that the patient may be pregnant or has a prior history of miscarriage or abortion. A personal history of exposure to radiation, especially in the treatment of childhood malignancies, is associated with a higher incidence of developing breast cancer (5). The goal of breast evaluation is to determine clearly whether the symptom represents a benign breast condition or may be indicative of a neoplastic process.

Physical Examination

Breast tumors, particularly cancerous ones, usually are asymptomatic and are discovered by the patient or through physical examination or screening mammography. Typically, the breast changes slightly during the menstrual cycle. During the premenstrual phase, most women have increased innocuous nodularity and mild engorgement of the breast. Rarely these characteristics can obscure an underlying lesion and make examination difficult. Findings should be carefully documented in the medical record to serve as a baseline for future reference.

Inspection

Inspection is performed initially while the patient is seated comfortably with her arms relaxed at her sides. The breasts are compared for symmetry, contour, and skin appearance. Edema or erythema is identified easily, and skin dimpling or nipple retraction is shown by having the patient raise her arms above her head and then press her hands on her hips, thereby contracting the pectoralis muscles (Fig. 21.1). Palpable and even nonpalpable tumors that distort Cooper’s ligaments may lead to skin dimpling with these maneuvers.

Figure 21.1 Raising the arm reveals retraction of the skin of the lower outer quadrant caused by a small palpable carcinoma. (From Giuliano AE. Breast disease. In: Berek JS, Hacker NF, eds. Practical gynecologic oncology. 4th ed. Baltimore, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2005:628, with permission.)

Palpation

While the patient is seated, each breast should be palpated methodically. Some physicians recommend palpating the breast in long strips, but the exact palpation technique used is probably not as important as the thoroughness of its application over the entire breast. One very effective method is to palpate the breast in enlarging concentric circles until the entire breast is covered. A pendulous breast can be palpated by placing one hand between the breast and the chest wall and gently palpating the breast between both examining hands. The axillary and supraclavicular areas should be palpated for enlarged lymph nodes. The entire axilla, the upper outer quadrant of the breast, and the axillary tail of Spence are palpated for possible masses. While the patient is supine with one arm over her head, the ipsilateral breast is again methodically palpated from the clavicle to the costal margin and from the sternum to the latissimus dorsi laterally. If the breast is large, a pillow or towel may be placed beneath the scapula to elevate the side being examined; otherwise, the breast tends to fall to the side, making palpation of the lateral hemisphere more difficult. The major features to be identified on palpation of the breast are temperature, texture and thickness of skin, generalized or focal tenderness, nodularity, density, asymmetry, dominant masses, and nipple discharge. Most premenopausal patients have normally nodular breast parenchyma. The nodularity is diffuse but predominantly in the upper outer quadrants, where there is more breast tissue. These benign parenchymal nodules are small, similar in size, and indistinct. By comparison, breast cancer usually occurs in the form of a nontender, firm mass with irregular margins. A cancerous mass feels distinctly different from the surrounding nodularity. A malignant mass may be fixed to the skin or to the underlying fascia. A suspicious mass is usually unilateral. Similar findings in both breasts are unlikely to represent malignant disease (6).

Breast Self-Examination

There is controversy about recommending breast self-examination (BSE). There is no evidence that doing BSE improves survival rates from breast cancer (7). Staunch opponents of BSE argue that it doubles a woman’s risk of undergoing a breast biopsy for benign pathology (8). BSE increases breast health awareness and helps promote early detection of cancer (9–11). Most breast cancers are detected by women themselves (48%), followed by breast imaging (41%), and by physician clinical examination in only 11% (12). Although young women have a low incidence of breast cancer, it is important to teach BSE early so it becomes habitual. Organizations such as the American Cancer Society sponsor courses in BSE. Reassurance, support, and patient education may encourage women to overcome psychological barriers to routine BSE (13). Such instruction is available through electronic resources (14).

The following seven “P”s represent the essential components of breast examination:

The woman should inspect her breasts while standing or sitting before a mirror, looking for any asymmetry, skin dimpling, or nipple retraction. Elevating her arms over her head or pressing her hands against her hips to contract the pectoralis muscles will highlight any skin dimpling. Finally, the woman should examine her breasts while bending over and leaning forward. While standing or sitting, she should carefully palpate her breasts with the fingers of the opposite hand. She should lie down and again palpate each quadrant of the breast as well as the axilla using the pads of the three middle fingers with three pressures—light, medium, and deep—covering the entire breast from the clavicle to the inframammary fold, from sternum to latissimus dorsi laterally. The area within the perimeter of the breast should be palpated, preferably using an up-and-down method called vertical stripe, rather than the concentric circular or radial methods, in which the edges of the breast tissue often are omitted. Many women feel anxious about performing breast examination. The examination may be performed while showering; soap and water may increase the sensitivity of palpation, and the privacy of the shower may provide a less anxiety-provoking environment.

It is helpful for all women to examine their breasts at the same time each month to develop a routine. Premenopausal women should examine their breasts monthly 7 to 10 days after the onset of the menstrual cycle. For postmenopausal women, selection of a specific calendar date is a helpful way to remember to perform a monthly BSE. Women should be instructed to report any abnormalities or changes to their physicians. If the physician cannot confirm the patient’s findings, the examination should be repeated in 1 month or after her next menstrual period.

Breast Imaging

Mammography

Screen-film mammography was considered the best method for imaging the breast (15). Full-field digital mammography, which records mammographic images on a computer, is a modification of screen-film mammography (16). Some advantages of digital mammography include lower radiation exposure, ability to manipulate a computerized image for optimal viewing, and access to distance consultations through telemammography (17). Studies comparing the sensitivity of full-field digital mammography with screen-film mammography in detecting cancer had mixed results. The Digital Mammographic Imaging Screening Trial (DMIST) consisted of 49,528 asymptomatic women presenting for screening mammography, who underwent both digital and film mammography. Results suggested that while the overall accuracy of digital and film mammography for screening breast cancer is similar, digital mammography may be more accurate in women under the age of 50 years, women with radiographically dense breast, and premenopausal or perimenopausal women (18).

Slow-growing breast cancers can be identified by mammography at least 2 years before the mass reaches a size detectable by palpation. These tumors have a less aggressive biologic behavior than interval breast cancers (19–21). Mammography is the only reproducible method of detecting nonpalpable breast cancer, but its use depends on the availability of state-of-the-art equipment and a dedicated breast radiologist.

Compression of the breast is necessary to obtain good images, and patients should be forewarned that breast compression is uncomfortable. With good technique and well-maintained modern equipment, exposure to radiation can be limited. Full-field digital mammography (FFDM) has a 22% lower mean glandular radiation dose than film-screen mammography per acquired view. FFDM delivers 1.86 mGy average breast radiation dose per view compared to 2.37 mGy for film screen (22).

Indications for Mammography

The indications for mammography are as follows:

Screening

Screening programs to evaluate asymptomatic, healthy women combine physical examination with mammographic screening to identify breast abnormalities. During the past 30 years, there was an increase in the use of mammography, mammographic screening, and public awareness of breast health care. The cancer detection rate for screening mammography is 5 per 1,000 screening examinations (24). The cancer detection rate is 11-fold higher, at 55 per 1,000 examinations, when breast imaging is performed for a specific finding (i.e., diagnostic imaging) (24). Of seven randomized mammographic screening trials performed, five demonstrated a reduction in overall mortality from breast cancer screening programs (25–32). A study from the Rhode Island Cancer Registry indicates that the institution of population-based breast cancer screening programs can result in the reduction in the median tumor size at initial detection from 2.0 to 1.5 cm, which is associated with a 25% reduction in mortality (33). A study from the Norwegian breast-cancer screening program was associated with a reduction in the rate of death from breast cancer, but the screening itself accounted for only about a third of total reduction (30). Detecting breast cancer before it spreads to the axillary nodes greatly increases the chance of survival; about 85% of women with such cancer will survive at least 5 years (31,34). Because breast cancer presents first as local disease, screening mammography for breast cancer in asymptomatic women can detect small tumors and offer a better prognosis. These tumors had less opportunity to metastasize regionally or systemically; thus women have more options for treatment with reduced toxicity.

The American Cancer Society published an extensive review of the benefits, limitations, and potential harms of screening mammography (35). It addresses the role of physical examination, discusses screening in older and high-risk women, and reviews the role of newer technologies. A summary of the guidelines recommends that women of average risk for breast cancer begin mammographic screening at age 40. The rationale for beginning mammographic screening at age 40 is a 24% reduction in mortality in screened populations (28). For women in their 20s and 30s, a clinical breast examination is suggested at least every 3 years, and preferably annually, as part of a well-woman examination. For women older than age 40 years, annual clinical breast examination and mammography are recommended. For older women, recommendations for mammographic screening may be individualized based on the presence of any comorbidities. Chronologic age alone should not be considered a contraindication to mammographic screening as long as a woman is in reasonable health and would be a candidate for breast cancer surgery (35). The American Geriatrics Society recommends annual or at least biennial mammography for women up to age 75 years, and after that age, every 2 to 3 years if the woman has a life expectancy of more than 4 years (36). The reasons for liberalization of the screening interval recommendations for older women include improved biology profile, slower growth rate, and lower risk for recurrence (37–41). The natural history of the disease in older women must be balanced against life expectancy as a function of overall health (42). For high-risk women, consideration can be given to earlier initiation of screening (5 to 10 years earlier than the age of the index case) and shorter intervals between screening, and the use of additional imaging modalities such as breast ultrasonography and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with dedicated breast coils. No screening test is perfect, and false-negative imaging studies or benign clinical examinations may lead the patient to an erroneous sense of well-being only to be confronted later with a subsequent cancer. Likewise, a false-positive result can lead to significant anxiety and unnecessary biopsy.

Mammographic Abnormalities

A mammographic abnormality includes a mass (solid versus cystic), microcalcifications (benign, indeterminate, suspicious), asymmetric density, architectural distortion, and appearance of a new density. There are eight morphologic categories of mammographic abnormalities (43,44):

Mammographic abnormalities should be visible on two views, usually craniocaudal (CC) and mediolateral oblique (MLO). The lesion should triangulate to the same location on those two views. Calcifications can be macrocalcifications, which are coarse and usually represent benign degenerative breast conditions. Calcifications associated with breast cancer are clustered pleomorphic microcalcifications; typically five to eight or more calcifications are aggregated in one part of the breast (45). These calcifications may be associated with a mammographic mass density. A mass density may appear without evidence of calcifications. It can represent a cyst, benign tumor, or a malignancy. A malignant density usually has irregular or ill-defined borders and may lead to architectural distortion, which may be subtle and difficult to detect in a dense breast. Other mammographic findings suggesting breast cancer are architectural distortion, asymmetric density, skin thickening or retraction, or nipple retraction. Examples of mammographic abnormalities can be found in several electronic sources (46).

Mammographic Reports

The American College of Radiology recommended the Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System (BI-RADS) as a standardized scheme for describing mammographic lesions (47). In the BI-RADS system, there are six categories for mammographic findings (other than incomplete) (43,44).

The patient should be referred for tissue diagnosis if the report identifies a lesion as a category 4 or 5 (47). A category 0 indicates incomplete evaluation, and further diagnostic studies are required. Category 3 connotes a finding that is most likely benign; a short-interval follow-up is recommended, and breast examination by an expert should be considered.

Correlation of Findings

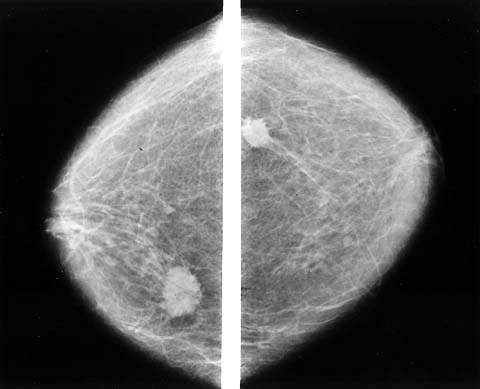

Biopsy must be performed on patients with a dominant or suspicious mass despite absence of mammographic findings (48). Mammography should be performed before biopsy so other suspicious areas can be noted and the contralateral breast can be checked (Fig. 21.2). Mammography is never a substitute for biopsy because it may not reveal clinical cancer, especially when it occurs in the dense breast tissue of young women with fibrocystic changes. The sensitivity of mammography is 75%, with a specificity of 92.3% depending on the patient’s age; breast density; use of hormone therapy; and the size, location, and mammographic appearance of the tumor (49). Mammography is less sensitive in young women with dense breast tissue than in older women, who tend to have fatty breasts, in which mammography can detect at least 90% of malignancies (50). Small tumors, particularly those without calcifications, are more difficult to detect, especially in women with dense breasts.

Figure 21.2 Bilateral mammography shows the extent of breast carcinoma, illustrating the importance of bilateral mammography in the workup of a clinically apparent mass. (From Giuliano AE. Breast disease. In: Berek JS, Hacker NF, eds. Practical gynecologic oncology. 4th ed. Baltimore, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2005:630, with permission.)

Ultrasonography

Breast ultrasonography is used for focused scanning of a questionable finding or for evaluation of a mammographic finding (51). Reliable, portable, computer-enhanced ultrasonography with high-frequency transducers and improved imaging is available to evaluate and treat problems of the breast (52). It is a sensitive, minimally invasive technique that is used frequently to evaluate some breast symptoms, especially in younger women with dense breast tissue, but is dependent on the availability of a skilled ultrasonographer (53). Some lesions can be detected only with ultrasonography (54). It is the preferred modality to distinguish a solid from a cystic mass (51). Breast ultrasonography is not recommended for routine screening, but is being studied as a means to screen women with dense breast tissue (54). Ultrasonography has a higher false-positive rate than mammography (51,53–55).

Following are indications for breast ultrasonography:

Palpable abnormality

Ambiguous mammographic findings

Silicone leak

Mass in woman younger than 30 years, lactating, or pregnant

Ultrasonography is useful in distinguishing benign from malignant lesions identified by mammography (56). Ultrasonography may be especially useful if the patient feels a mass, but the physician cannot detect an abnormality and the mammogram does not disclose one. It may identify cancers in the dense breast tissue of premenopausal women, but it is usually used to distinguish a benign cyst from a solid tumor. Ultrasonography cannot reliably detect microcalcifications, and it is not as useful as mammography in assessing women with fatty breasts.

Handheld or real-time ultrasonography is 95% to 100% accurate in differentiating solid masses from cysts (57). This finding is of limited clinical value because a dominant mass should be evaluated by biopsy, and a cystic mass can be studied by needle aspiration, which is far less expensive than ultrasonography. If a lesion proves to be a simple cyst, no further evaluation is necessary. Rarely ultrasonography may identify a small cancer within a cyst, an intracystic carcinoma. These complex cysts warrant surgical biopsy.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Magnetic resonance imaging may be of value in assessing breast lesions of an indeterminate nature detected by clinical and mammographic examination or occurring in patients who have implants (58). Both MRI and positron emission tomography (PET) are used to identify occult lesions, and MRI is increasing in popularity as a means of imaging the breast (58–60). It tends to be highly sensitive but not specific, leading to biopsies of benign lesions. Image enhancement with gadolinium discriminates between benign and malignant lesions with varying degrees of accuracy.

Several roles are proposed for breast MRI. The lack of radiation exposure makes MRI theoretically an ideal method for screening of healthy women, but widespread use is not cost-effective. Focal asymmetry is usually benign but can represent a malignancy. MRI may help identify those patients with focal asymmetric areas who should undergo biopsy. A scar can easily be distinguished from recurrent tumor based on the evaluation and diminution of the scar over time. Some scars do not resolve rapidly and are confused with cancer or, more commonly, with recurrent cancer after breast-conserving surgery and whole breast irradiation. Ideally, such cases are evaluated with MRI, sometimes obviating the need for biopsy. MRI is extremely useful in identifying silicone released by ruptured breast implants in patients with augmented breasts (Fig. 21.3). In patients with implants, MRI with gadolinium may be performed to detect breast cancer even if silicone release is not suspected. There may be a role for MRI in evaluation of specific conditions. It is used for the following indications:

Figure 21.3 Mammography shows implant and extracapsular free silicone (arrow).

The American Cancer Society recommends annual MRI screening for women who are high risk (greater than 20% lifetime risk) and consideration given to women with moderate risk (15% to 20% lifetime risk) (61). A study from the Netherlands in high-risk women reported 71% sensitivity for MRI compared with 17.9% for clinical breast examination and 40% for mammography (62). The International Cooperative Magnetic Resonance Mammography Study will help identify the advantages and limitations of MRI. At present, MRI should be considered only after conventional imaging is performed; it should not be used as a screening tool or a substitute for mammography or biopsy. Centers that perform MRI should have the ability to perform MRI-guided biopsies of lesions detected with MRI only and that are not visible with mammogram or ultrasound.

Positron Emission Tomography Scan

PET scanning is a diagnostic modality that assesses the metabolic activity of tumors. Radioactive fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) is an analogue of glucose that is metabolized by tissues of high metabolic activity. Although not specifically approved for the initial diagnosis of breast cancer or for staging the axilla, it can be useful in patients with advanced disease (59,63). This technique is used to identify occult breast lesions with positive axillary lymph nodes (59).

Breast Tissue Evaluation: Histology and Cytology

The safest course is tissue or cytologic biopsy evaluation of all dominant masses found on physical examination and, in the absence of a mass, evaluation of suspicious lesions shown by breast imaging. Over 1 million women have breast biopsies each year in the United States. Between 70% and 80% of these biopsies yield a benign lesion (64). The diagnosis of a benign breast lesion versus breast cancer is often difficult to determine based on clinical examination and requires evaluation of tissue by fine needle aspiration cytology (FNAC), core needle biopsy (CNB), or excisional biopsy (EB). Both FNAC and CNB are reasonable techniques for the evaluation of a palpable or image-identified lesion. CNB evolved as the diagnostic procedure of choice. More than half of all breast biopsies use a core-needle technique. The sensitivity of CNBs performed using either stereotactic or ultrasound guidance is 97% to 99% (65). CNB is used increasingly to diagnose breast cancer and to determine tumor histology, grade, and marker expression; select neoadjuvant therapy; and predict sentinel lymph node status (66). CNB and fine needle aspiration (FNA) are less invasive and achieve better cosmesis than excisional or even incisional biopsy. The main limitations of FNA are high rate of insufficient sampling and inability to distinguish invasive from noninvasive cancers. CNB is a well-accepted alternative to surgical biopsy and can avoid surgical biopsies in most patients (67). Investigators of the Fifth Radiologic Diagnostic Oncology Group demonstrated that image-guided biopsy of breast lesions provides high diagnostic accuracy. The sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy of CNB were 0.91, 1.00, and 0.98, respectively (68).

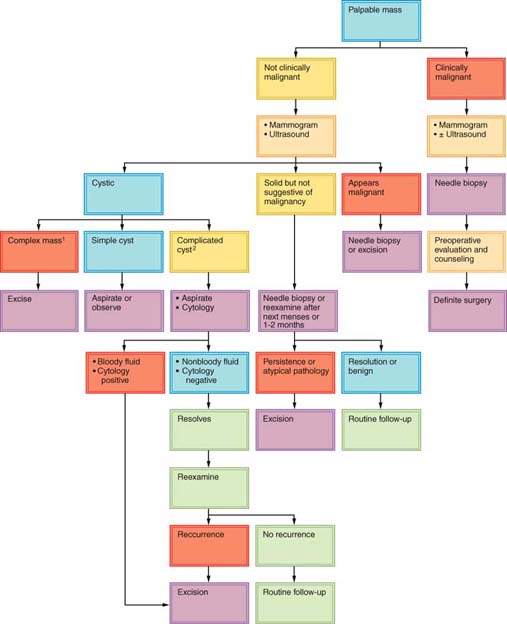

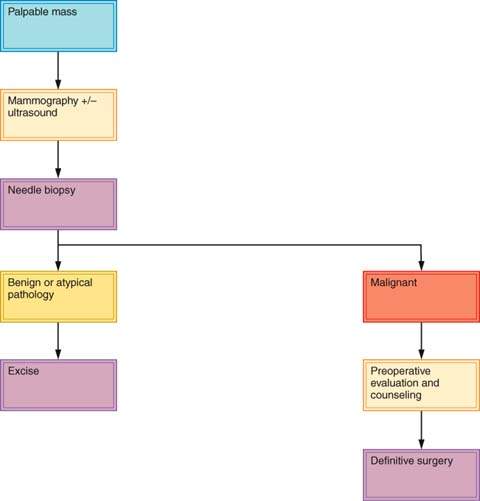

About 30% of lesions suspected to be cancer prove on biopsy to be benign, and about 15% of lesions believed to be benign prove to be malignant (23). Dominant masses or suspicious nonpalpable breast lesions require histopathological examination. Histologic or cytologic diagnosis should be obtained before the decision is made to monitor a breast mass (69). An exception may be a premenopausal woman with a nonsuspicious mass presumed to be fibrocystic disease. An apparently fibrocystic lesion that does not completely resolve within several menstrual cycles should be sampled for biopsy. Any mass in a postmenopausal woman who is not taking estrogen therapy should be presumed to be malignant. Some clinicians will monitor a mass when results of the clinical diagnosis, breast imaging studies, and cytologic studies are all in agreement, such as with fibroadenoma. Many clinicians will not leave a dominant mass in the breast even when FNAC or CNB results are negative, unless the FNA or CNB shows fibroadenoma. Such cases require periodic follow-up. Some surgeons excise lesions when the sampling technique shows only fibrocystic disease. Figures 21.4 and 21.5 present algorithms for management of breast masses in premenopausal and postmenopausal patients. Simultaneous evaluation of a breast mass using clinical breast examination, radiography, and needle biopsy can lower the risk of missing cancer to only 1%, effectively reducing the rate of diagnostic failure and increasing the quality of patient care (70).

Figure 21.4 Algorithm for management of breast masses in premenopausal women. (Revised and updated from Giuliano AE. Breast disease. In: Berek JS, Hacker NF, eds. Practical gynecologic oncology. 4th ed. Baltimore, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2005:640, with permission.)

Figure 21.5 Algorithm for management of breast masses in postmenopausal women. (Revised and updated from Giuliano AE. Breast disease. In: Berek JS, Hacker NF, eds. Practical gynecologic oncology. 4th ed. Baltimore, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2005:641, with permission.)

If the presence of breast cancer is strongly suggested by physical examination, the diagnosis can be confirmed by FNAC or CNB, and the patient may be counseled regarding treatment. Treatment should not be determined based on results of physical examination and mammography alone, in the absence of biopsy results. The most reasonable approach to the diagnosis and treatment of breast cancer is outpatient biopsy (either FNAC, CNB, or EB), followed by definitive surgery at a later date if needed. This two-step approach allows patients to adjust to the diagnosis of cancer, carefully consider alternative forms of therapy, and seek a second opinion. Studies show no adverse effect from the 1- to 2-week delay associated with the two-step procedure (71). Because cancer is found in the minority of patients who require biopsy for diagnosis of a breast mass, definitive treatment should not be undertaken without an unequivocal histologic diagnosis of cancer.

Fine-Needle Aspiration

With FNAC, cells from a breast tumor are aspirated with a small (usually 22-gauge) needle and examined by a pathologist. Precise guidelines for this technique are available (72). It can be performed easily, with no morbidity, and is much less expensive than excisional or open biopsy. It requires the availability of a pathologist skilled in the cytologic diagnosis of breast cancer to interpret the results, and it is subject to sampling problems, particularly when lesions are deep. Cytologic diagnoses must be correlated with clinical and imaging findings to achieve triple-test concordance and to decrease the false-negative rate (73). The triple-test concordance (i.e., concordance between fine-needle aspiration, physical examination, and mammography) is the foundation of breast evaluation. The triple-test results are more powerful than each modality alone (74). The incidence of false-positive diagnoses was 0% to 0.3%, and the rate of false-negative diagnoses was 1.4% to 2.3% in several recent studies (74,75).

Core Needle Biopsy

A core of tissue can be obtained from palpable lesions using a large cutting needle (76). Image-guided large-core needle biopsy is a reliable diagnostic alternative to surgical excision of suspicious nonpalpable breast lesions (77). As in the case of any needle biopsy, the main drawback is false-negative findings caused by improper positioning of the needle. False-negative findings may be reduced if core biopsy is performed with ultrasonographic guidance. The interpretation of results from CNB is classified by categories B1 to B5 (78):

Open Excisional Biopsy

Open biopsy with local anesthesia as a separate procedure before deciding on definitive treatment is the most reliable means of diagnosis. Its utility is reserved for when the results of needle biopsy are nondiagnostic or equivocal.

Histologic Analysis

Histologic evaluation with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining confirms benign or malignant disease. Images of benign and malignant breast lesions can be viewed through the Internet Pathology Laboratory for Medical Education (79). Assessment of prognostic factors, tumor grade; estrogen, progesterone, her-2/neu receptor status; and proliferative indices is performed on paraffin-fixed tissue by immunohistochemistry (78). Her-2/neu assessment in breast cancer by immunohistochemistry (IHC) is appropriate for patients with tumors that score 3+. Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) is recommended for 2+ IHC to more accurately assess her-2/neu amplification and provide better prognostic information (80).

Ductal Lavage Cytology

Ductal lavage using a microcatheter is a modality that was investigated in high-risk women (81). Patients undergo gentle nipple suction to elicit nipple fluid. A duct that yields fluid is cannulated with a microcatheter, and 10 to 20 mL of saline are introduced in 2- to 4-mL increments. The cytologic assessment of a sample obtained by ductal lavage is more sensitive than that of nipple aspiration. Ductal lavage performed to identify abnormal cells is not an effective tool in detecting breast cancer and is rarely performed (81).

Benign Breast Conditions

Benign breast disorders account for most breast problems. These conditions are frequently considered in the context of excluding breast cancer and often are unrecognized for their own associated morbidity (82). To provide appropriate management, it is important to consider benign breast disorders from four aspects: (i) clinical picture, (ii) medical significance, (iii) treatment intervention, and (iv) pathologic etiology (83). A framework for understanding benign breast problems is called Aberrations of Normal Development and Involution (ANDI) (2,82,83). It includes symptoms, histology, endocrine state, and pathogenesis in a progression from a normal to a disease state. Most benign breast conditions arise from normal changes in breast development, hormone cycling, and reproductive evolution (82).

Three life cycles reflect different reproductive phases in a woman’s life and are associated with unique breast manifestations.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree