CHAPTER 16 Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is the most common neurobehavioral health condition among children. Although it has been the subject of great controversy, it is also the most studied neurobehavioral condition of childhood with the greatest empirical basis for evaluation and treatment. Affected children usually present with behavioral problems or academic difficulties. It is important to determine whether these concerns arise from true ADHD, from a condition that mimics ADHD, from ADHD complicated with by a comorbid diagnosis, or from normal activity for the child’s age. Understanding the current recommendations for the evaluation, diagnosis, treatment, and management is imperative to provide these children the best care possible. Guidelines have been published by experts in pediatrics1,2 and mental health3,3a for the diagnosis and treatment of ADHD. These recommendations, along with the criteria set forth in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition (DSM-IV),4 provide for greater uniformity of the diagnosis, treatment, and management processes in the care of children with this complicated symptom complex.

HISTORY

In the media, ADHD is often represented as a newly discovered entity. In reality, the core symptoms of ADHD have been puzzling health care providers since the mid-1800s. The first literary description was provided in a children’s book written in 1848 by a German physician, Heinrich Hoffmann5:

The poem continues, giving a description of Fidgety Phil’s antics, which resemble hyperactive/impulsive symptoms. Hoffmann also described inattentive symptoms in another character, Johnny Head-In-Air. Johnny was watching the birds and the sun and never knew what hit him when he fell headlong into the river and had to be fished out.5

A perhaps more parent-friendly description appeared soon after in 1851 in a story by George Sand. In this story, a mother dies young, leaving three children in the care of their father and grandparents. The woman’s father encourages the father to remarry because the grandparents cannot keep up with the care of the children, particularly “Sylvain, who is not four years old, and who is never quiet day or night. He has a restless disposition like yours; that will make a good workman of him, but it makes a dreadful child, and my old wife cannot run fast enough to save him when he almost tumbles into the ditch, or when he throws himself in front of the tramping cattle.”6 This description highlights the familial nature of the disorder, its early onset, and the burden of care that it places upon families.

At first, in dealing with this disorder, the primary focus was on conduct. In 1902, Still described children with ADHD symptoms and believed these children had a “defect in moral control.”7 He stated the “problem resulted in a child’s inability to internalize rules and limits, and additionally manifested itself in patterns of restlessness, inattentive, and over-aroused behaviors.”7 This stress on control of behavior has returned, renamed as response inhibition or executive dysfunction.8 In 1937, a stimulant, racemic amphetamine (Benzedrine), was noted to improve the behaviors in children affected with these core symptoms.9 Methylphenidate, whose effects were similar to those of the amphetamines, was released for general use in 1957.10

As research has revealed more about this troubling symptom complex of inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity, there have been many causal theories and name changes. The cause of the disorder was first thought to be brain damage when some of the children recovering from encephalitis caused by the worldwide influenza epidemic in 1917 exhibited symptoms of restlessness, inattention, impulsivity, easy arousability, and hyperactivity11,12 When brain damage was found to be less evident in many children exhibiting symptoms, the name was changed to minimal brain damage and minimal cerebral dysfunction. It shifted from an etiological name to a behavioral descriptive name in the late 1960s. In the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 2nd edition (DSM-II), it was labeled Hyperkinetic Impulse Disorder,13 which reflected a focus on the hyperactive symptoms. In the third edition (DSM-III),14 the name underwent further change as the focus shifted from hyperactive symptoms to inattention, with the name Attention Deficit Disorder, on the basis of research by Douglas that demonstrated deficiencies in continuous performance and similar vigilance tasks.15 The name Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder was introduced in the revision of the third edition (DSM-III-R).16 The latest terminology is defined in the fourth edition (DSM-IV),4 in which Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder is divided into three subtypes: primarily inattentive type, primarily hyperactive-impulsive type, and combined type.4

The confusion over the causes and even the specific definition of this symptom complex is demonstrated by the frequent name changes. This is perhaps not surprising, inasmuch as the intimate interrelationship between attention and intention was pointed out as early as 1890 by William James: “The essential achievement of the will, in short, when it is most ‘voluntary,’ is to attend to a difficult object and hold it fast before the mind. The so-doing is the fiat; and it is a mere physiological incident that when the object is thus attended to, immediate motor consequences should ensue.”17

PREVALENCE

Researchers have identified individuals with ADHD symptoms in every nation and culture studied,18 but determining the true prevalence rate of ADHD has been a challenging task. Prevalence estimates for ADHD vary, depending on the diagnostic criteria used, the population studied, and the number of sources necessary to make the diagnosis.2 Several features of the disorder are major contributors to the challenge. First, there are no known specific biological markers (laboratory tests or image studies) that can discriminate children with ADHD from children with another neurobehavioral disorder or from normal controls. Second, the behaviors observed in ADHD differ in quantity, not quality, from those of typical children. This contrasts to disorders such as schizophrenia, in which the presence of auditory hallucinations is qualitatively distinct from normal experience, or conduct disorder, in which a child may willfully engage in criminal activity. Third, the frequency of these behaviors is observed and reported by the child’s caregivers; therefore, the diagnosis must rely on the judgment of persons who do not share any uniform training or view of child development and whose interrater reliability is unknown. Fourth, there is no consensus about what frequency of any given behavior is normal at any given age; for example, in assessing intelligence, there are clear normative guidelines for which tasks can be accomplished at which age. Fifth, the behaviors are context specific; in situations of stress, most people exhibit inattention, overactivity, and impulsive behaviors.18a Sixth, the ADHD core symptoms and signs are not specific to ADHD; for example, the continuous performance task that was used to establish the attentional component of ADHD was first developed to study subjects with schizophrenia.

The modifications in diagnostic criteria over time have further complicated the process of determining the true prevalence of ADHD. The most recent change, from only one subtype in DSM-III-R to three subtypes in DSM-IV, has increased the prevalence rates. In addition to the challenges to making accurate diagnoses, studies of prevalence rates are dependent on the sample studied. The rates are different in a sample referred to a mental health clinic from those in a primary care sample or from a community/school sample. In view of these challenges, it is not surprising that varying rates have been reported. The prevalence has ranged from 4% to 12% (median, 5.8%).2 Rates are higher in community samples (10.3%) than in school samples (6.9%), and higher among male subjects (9.2%) than among female subjects (3.0%).2 This effect also seems to extend even into population-based studies. One population-based survey in which identical interview strategies were used in four different communities revealed prevalence rates that varied from 1.6% to 9.4 % (pooled mean, 5.1%).19

As with other neurodevelopmental disorders, ADHD is more common in boys and men, and male : female ratios are 5 : 1 for predominantly hyperactive/impulsive type and 2 : 1 for predominantly inattentive type.20,21 Many experts believe this gender difference exists partially because boys commonly present with the externalizing hyperactive/impulsive symptoms such as aggression and overactivity, whereas girls often present with internalizing inattentive symptoms such as underachievement and daydreaming.20,21 This difference is thought to lead to an earlier referral for boys and a later referral and, possibly, underdiagnosis for girls.

ETIOLOGY

Approximately 20% to 25% of children who have ADHD also have a diagnosis that can be associated with an organic cause. Prenatal exposure to some substances may be dangerous to the developing fetal brain. For example, children born with fetal alcohol syndrome may exhibit the same hyperactivity, inattention, and impulsivity as do children with ADHD22 (see Chapter 11). Exposure to other toxins, including cocaine, nicotine, and lead, or the occurrence of trauma or infection that leads to central nervous system damage may produce the ADHD symptom complex.22 In the other 75% to 80% of affected children, ADHD is thought to have a polygenic basis. Genetic evidence of ADHD has been provided by studies involving adoption, twins, siblings, and parents. In twin studies, the heritability of ADHD has been estimated at 0.75 (75% of the variance in phenotype can be attributed to genetic factors). If a child with ADHD has an identical twin, the twin has a greater than 50% chance of developing ADHD.23 Family studies have also demonstrated that adoptive relatives of children with ADHD are less likely to have the disorder24,25 and that first-degree relatives have a greater risk than do controls.26–28

Neuroimaging studies with magnetic resonance imaging, positron emission tomography, and single photon emission computed tomography have demonstrated differences in brain structure and function between individuals with ADHD and controls in the basal ganglia, cerebellar vermis, and frontal lobes. These areas are thought to regulate attention: The basal ganglia help inhibit automatic responses, the vermis is thought to regulate motivation, and the prefrontal cortex helps filter out distractions.23,29,30 Investigations of the brain’s response to stimulants have implicated the dopaminergic system as a possible contributor to the disorder. Dopamine can inhibit or intensify the activity of other neurons. It is also possible that the norepinephrine receptors may be involved; however, this has yet to be confirmed. Specific gene associations have been identified in a small proportion of individuals with ADHD. These include the dopamine transporter gene (DAT1), the D4 receptor gene (DRD4), and the human thyroid receptor–β gene.31–34 Currently, imaging and genetic analysis are not helpful on a clinical basis because of the wide variation of size and function of the brain in individuals with ADHD and those without ADHD and the small numbers who have identified gene abnormalities.

PROGNOSIS

It was once thought that children outgrew ADHD. It is now known that 70% to 80% of children who have ADHD continue to have difficulty through adolescence and adulthood.35 The manifestation of symptoms usually changes through a child’s lifetime. In general, hyperactive core symptoms decrease over time, whereas inattentive symptoms persist.35 Some children learn to adapt and are able to build on their strengths and minimize their impairment. The majority continues to struggle, with their impairment manifesting in different ways. The true outcome depends on the severity of symptoms, presence or absence of coexisting conditions, social circumstances, intelligence, socioeconomic status, and treatment history.35 Adolescents with ADHD have higher rates of school failure, motor vehicle accidents, substance abuse, and encounters with law officials than do the general population.36 Adults with ADHD may achieve lower socioeconomic status and have more marital problems than do the general population.36

EVALUATION AND DIAGNOSIS

To establish the degree of symptoms and their functional significance, and to rule out alternative causes, information must be gathered from many sources. This includes obtaining a thorough history and physical examination, reviewing ADHD-specific behaviors in multiple settings, and determining the presence of any comorbid conditions. For children, the sources must include, at a minimum, their parents and teachers.1 Teachers observe children for up to 6 hours a day. They see them in comparison with a group of same-age peers and in situations that require the children to pay attention, control their activity level, and resist their impulses. When possible, it is also helpful to obtain information from other observers, such as coaches, scout leaders, and grandparents. Direct observation of a child’s behavior in the classroom can provide some of the most objective information, if it is available, but this is labor intensive and therefore has to be limited to small samples of time.1,4 Observations in the pediatric office are frequently not useful because they may not be well correlated with the child’s behavior in the home, classroom, and community.

ADHD remains a clinical diagnosis based on specific criteria and clinical impression. It is important to use a structured, systematic approach in evaluating children with behavioral problems and not to rely on clinical judgment alone. Table 16-1 is a general overview of the recommended guidelines for diagnosing ADHD.1,3,3a,37 Depending on the situation, many health care providers obtain information from behavioral rating scales before proceeding to an office evaluation. Scales in which DSM-IV criteria are used are helpful1 (e.g., the Vanderbilt Assessment Scales,21 DuPaul and associates’ ADHD Rating Scale-IV38; the Revised Conners Rating Scales39). Broadband scales (e.g., Child Behavior Checklist40 and Behavior Assessment System for Children41) were not found to be as helpful in making an ADHD diagnosis but do help screen for co-occurring conditions.1 Other clinicians are more comfortable gathering information from an office visit to gain a clearer picture of the problems before proceeding to the next step. In evaluation of a child for ADHD, the differential diagnosis and common comorbid diagnoses are quite extensive (Tables 16-2 and 16-3). Keeping these in mind when the history and physical examination are updated is important because many conditions can mimic or coexist with ADHD. The correct diagnosis dictates the proper treatment and prognosis for patients. Young children most commonly have comorbid complications of developmental delays, communication disorders, developmental coordination disorder, reading and writing problems, tic disorder, oppositional defiant disorder, anxiety, or autistic behaviors, whereas older children and adults may have comorbid symptoms related to depression, anxiety, substance abuse disorder, or conduct disorder. One extensive review revealed the following percentages of comorbid diagnoses: 35%, oppositional defiant disorder; 26%, conduct disorder; 18%, depression; 26%, anxiety; and 12%, learning disorders.2

ADHD, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; DSM-IV, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition.4

TABLE 16-2 Differential and/or Comorbid Diagnoses

TABLE 16-3 Comorbid Protocol: Does Child Have Symptoms of Comorbid Conditions?

| Learning disorder or language disorder | If symptoms indicate some effect of behavior problems on learning, consider referral to school study team for Section 504 classroom accommodations |

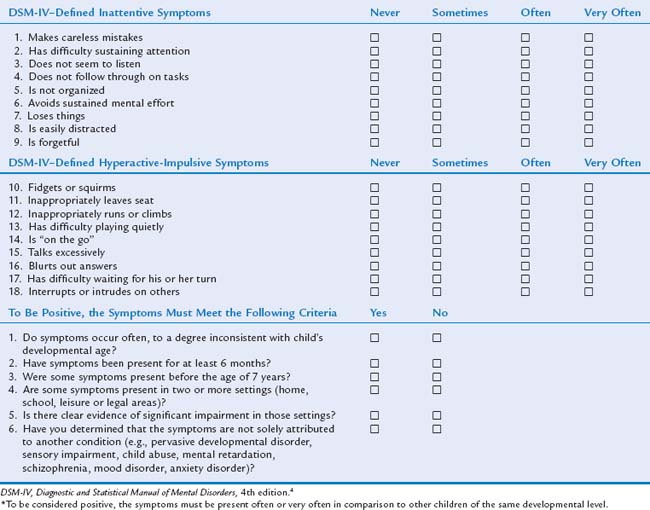

DSM-IV Criteria

The DSM-IV4,4a provides the diagnostic criteria currently used in the United States. It contains a description of 18 core symptoms focusing on the main problems of inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity (Table 16-4). The child must exhibit at least six of nine inattentive behaviors inappropriately often to meet the criteria for ADHD, inattentive subtype; at least six of nine hyperactive/impulsive behaviors inappropriately often to meet the criteria for ADHD, hyperactive/impulsive subtype; and six of nine behaviors in both dimensions to meet the criteria for ADHD, combined subtype. In addition to the presence of the core symptoms:

It is important to remember that attention is inherently an interaction between child and environment. A child’s behavior varies with setting, situation, and stimulus. It is typical for symptoms to be minimal when there is novelty, immediate reinforcement, or increased stimulus salience involved (such as a movie, video game, or doctor visit). Symptoms are often most intense when the situation is less interesting or unstructured and requires concentration, such as listening to instructions, doing homework, or sitting in religious services.36,42

Associated problems can increase the attentional demands of a situation. Cognitive or learning disabilities, family disruption, or dysfunctional classrooms can all increase inattentive behaviors. For these differences, it is important to obtain information from multiple sources. Parent and teacher behavioral rating scales specific for ADHD can effectively provide information required to make a specific diagnosis. Broadband scales are less useful for establishing specific diagnoses but can be useful in screening for comorbid conditions.2 This can also be achieved by verbal interview, if the clinician has the time, and is systematic in the interview process. The interview can sometimes reveal biases of some reporters: for example, teachers who believe that ADHD does not exist or parents who resist accepting diagnoses of learning disorders. Sometimes a child has few symptoms in a very structured special education setting but exhibits impairment in typical settings such as regular education, in the community, and at home.

Common Noncore Symptoms of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder

In addition to the DSM-IV core symptoms, there are a number of symptoms that are frequently seen in ADHD, but do not imply an additional comorbid diagnoses. These include social skills dysfunction, problems with self-esteem, motor coordination, and sleep. Social skills deficits have been documented in preschool, middle childhood, and adolescent children with ADHD.42a,42b In long-term follow-up studies of hyperactive children, investigators have reported reduced numbers of friends, low measures of self-esteem, and an increase in antisocial behavior.43 Results of one study suggested that some of these difficulties may arise from an inappropriately high level of self-esteem or “positive illusory self-concept” on the basis of sociometric analyses of child, peer, and teacher ratings of social competence.44

Sleep disturbances are common in children with ADHD45–47 but may not come to the attention of the clinician until after the presenting behavioral crisis has resolved. There may then be confusion as to whether the sleep disturbance is secondary to the ADHD or is a side effect of stimulant medication. In most placebo-controlled studies of stimulant medication, investigators have reported an increase in sleep problems, although several sleep laboratory studies have not demonstrated worsening of sleep disturbance with stimulant therapy.48,49 Reports of increased rates of inattention in children referred for sleep evaluations and improvement after tonsillectomy and adenoidectomy50–52 underscore the importance of a good sleep history in an initial ADHD evaluation. In one comparison of children with “significant” ADHD symptoms with those with “mild” symptoms, findings suggested that obstructive apnea was uncommon in “significant” ADHD but caused a syndrome of “mild” inattention and distractibility.53

TREATMENT

It is important to understand that ADHD is a chronic illness for which there is no cure. However, even though there is no curative treatment for the condition, ongoing management can minimize the extent of impairment. First, it is important to educate the parents and patients about the condition and its treatment. This education can help to demystify the condition and clarify many misconceptions raised in the popular press or prevalent in the community. Educated families are better able to work as partners with the clinician in establishing and maintaining an effective treatment program. The treatment plan should be carefully tailored for each individual patient (Table 16-5). When a family is invested in the treatment plan, there is an increased chance of adherence to the regimen.3 This investment can be maximized by educating the family about their options and by taking individual needs, family preferences, opinions, and lifestyle into account in designing the regimen. For the most favorable outcomes, it is necessary to develop a multidisciplinary approach involving the child, caregiver, educators, and clinician. Communication between home, school, and clinician is needed for monitoring outcomes and making quick changes when needed. Three treatment strategies have been studied and shown effective in treating ADHD: medication, behavioral modification, and a combination of both.54,55

IDEA, Individuals with Disabilities Education Act of 2004; IEP, Individualized Education Plan.

Family Education

Educating the caregivers and child about ADHD is essential to good treatment outcomes. Education can help the family come to grips with the diagnosis (Table 16-6). Understanding that ADHD is a brain-based problem and not caused by poor parenting or that it is not intentional misbehavior by the child can relieve guilt and help alleviate stress and frustration that have been present for many years. Raising, teaching, or being a child who has difficulty sustaining attention, filtering out stimuli, learning from past mistakes, and regulating activity level can be very challenging. Being able to change the focus on helping the child improve function instead of always pointing out bad behaviors will improve satisfaction with the child’s response to treatment. ADHD runs in families, and many parents of affected children had difficult school experiences themselves. A physician or other medical personnel moderating interaction between home and school can help build trust and cooperation.

TABLE 16-6 Education for Child, Parents/Caregivers, and Teacher