13.1 Atopy

General principles

Definition, prevalence and burden of disease

There is a marked variation in the global and regional prevalence of the atopic diseases, with the highest disease burden in industrialized countries and urbanized communities. In these countries, atopic diseases are now the commonest ailments of childhood, and Australian and New Zealand children have the fifth highest global rates of atopic disease (Table 13.1.1). Since the industrial revolution, the prevalence of atopic diseases has been increasing in most communities, for reasons that are not yet apparent. Environmental factors are thought to account for the variable and increasing prevalence of atopic disease. A commonly cited hypothesis, the ‘hygiene hypothesis’, proposes that the lack of early childhood exposure to infections and/or other environmental factors (such as bacterial endotoxin) may predispose to atopic disease in genetically susceptible individuals. Such a hypothesis can be supported by epidemiological and possibly immunological evidence.

Table 13.1.1 Prevalence of atopic disorders among Australian children

| Disorder | 6–7-year-olds (%) | 13–14-year-olds (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Eczema ever | 23 (11) | 16 (10) |

| Asthma ever | 27 (25) | 28 (29) |

| Hayfever ever | 18 (12) | 43 (20) |

Values in parentheses show the percentage that currently have the condition. Data obtained from the International Study of Asthma and Allergy in Childhood questionnaire-based survey of 10 914 children in Melbourne, Sydney, Adelaide and Perth.

Pathogenesis

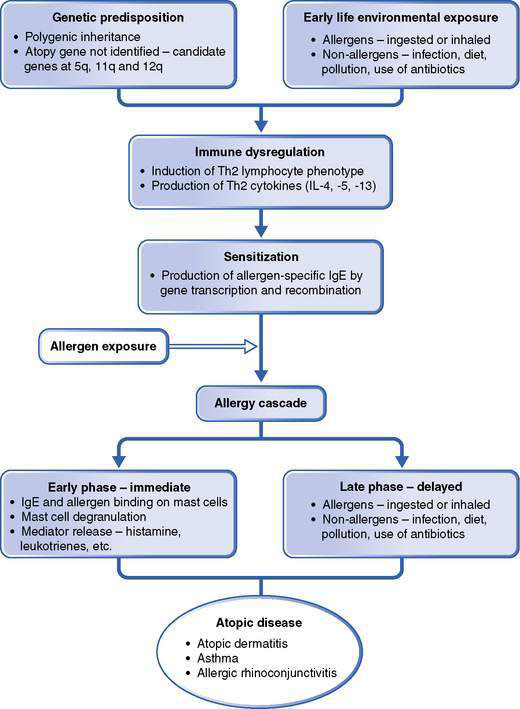

Although atopy is defined by an excessive production of IgE, this is only one of many immunological changes that characterize the allergic diseases, as these are also associated with a complex dysregulation of the humoral and cellular immune systems (Fig. 13.1.1). For this process to occur, both a genetic predisposition and early life environmental exposure are important. During early life, naive T-helper lymphocytes respond in a particular way to environmental allergen exposure as well as a host of other non-allergen immunomodulatory factors (such as endotoxin). T-regulatory cell function and the pattern of cytokine secretion are central to the factors that result in the production of antibodies, including IgE.

Approach to diagnosis, investigation and management

History and examination

The history and examination should cover the following aspects:

• Severity of symptoms and degree of disability

• Environmental history – identification of triggers

Box 13.1.1 Allergens that may trigger symptoms in atopic children

On examination, atopic children may have a typical appearance (Table 13.1.2).

Table 13.1.2 Examination of the atopic child

| System | Clinical findings |

|---|---|

| Growth | Weight |

| Height | |

| Facies | Facial pallor |

| Allergic shiners – infraorbital dark circles due to venous congestion | |

| Dennie–Morgan lines – wrinkles under both eyes | |

| Mouth breathing | |

| Dental malocclusion – from long-standing upper airway obstruction | |

| Sinus tenderness | |

| Skin | Atopic dermatitis |

| White dermatographism – white discoloration of skin after scratching | |

| Xerosis – dry skin | |

| Urticaria and/or angio-oedema | |

| Nose | Horizontal nasal crease |

| Inferior nasal turbinates – pale and swollen | |

| Clear nasal discharge | |

| Respiratory | Chest deformity – Harrison sulcus, increase in anteroposterior diameter |

| Respiratory distress | |

| Wheeze and/or stridor | |

| Eyes | Conjunctivitis |

| Subcapsular cataracts associated with conjunctivitis | |

| Ears | Tympanic membrane dull and retracted |

| Throat | Tonsillar enlargement |

| Postpharyngeal secretions and cobblestoning of mucosa | |

| Cardiovascular | Blood pressure |

Assessment

Once the history and examination are completed, there is seldom difficulty in diagnosing the presenting atopic disease. However, as many children manifest more than one atopic disease, it is important to consider whether any other atopic condition is present. A differential diagnosis should be considered, as uncommon disorders may present similarly to an atopic disease (Table 13.1.3).

Table 13.1.3 Differential diagnosis of atopic disease

| Atopic disease | Differential diagnosis |

|---|---|

| Atopic dermatitis | Seborrheic dermatitis |

| Psoriasis | |

| Wiskott–Aldrich syndrome* | |

| Hyper-IgE syndrome* | |

| Asthma | Infection – viral, bacterial, mycobacterial |

| Congenital anomaly (e.g. vascular ring) | |

| Cystic fibrosis | |

| Immunodeficiency disease | |

| Aspiration syndrome secondary to gastro-oesophageal reflux, incoordinate swallowing or tracheo-oesophageal fistula | |

| Inhaled foreign body | |

| Cardiac failure | |

| Allergic rhinitis | Infective rhinitis |

| Non-allergic rhinitis | |

| Vasomotor rhinitis | |

| Rhinitis medicamentosa | |

| Sinusitis | |

| Adenoidal hyperatrophy | |

| Nasal polyps | |

| Nasal foreign body | |

| Choanal atresia (unilateral, bilateral) |

* These immunodeficiency diseases may have atopic dermatitis as a component.

Investigations

Investigations in the atopic child are limited. Total IgE concentration is raised in the majority of children with atopic disease but there is substantial overlap with values in non-atopic children. Measurement of total IgE levels is seldom indicated. Allergen-specific IgE (ASE) is more useful and can be determined using both in vivo (skin testing) and in vitro (serological) methods (Table 13.1.4). Measurement of ASE may be helpful in identifying a specific allergen trigger. However, interpretation of the skin test or ASE result is critical:

• The presence of specific IgE to an allergen is only one factor in establishing whether the allergen is a clinically significant trigger.

• The result should always be correlated with the history and/or a trial of allergen avoidance with or without subsequent challenge.

• The predictive value of a negative result is higher than the predictive value of a positive result.

• The skin test or ASE result should always be discussed with the parent or caregiver to avoid misinterpretation.

• Failure to discuss often leads to inappropriate avoidance measures such as excluding foods from the diets of children solely on the basis of a positive skin test or ASE result.

Table 13.1.4 Determination of allergen-specific IgE

| Skin testing | Serology | |

|---|---|---|

| Method | Skin puncture test | UniCAP |

| Availability | Limited | Widely |

| Expense | Cheap | Expensive |

| Results | Immediate | Delayed |

| Risk of anaphylaxis | Rare | Nil |

| Interference | Antihistamines | High total IgE |

| Extensive atopic dermatitis | ||

| Dermatographism | ||

| Sensitivity | ++++ | ++ |

| Specific | ++++ | ++ |

Ig, immunoglobulin; UniCAP, radioallergosorbent test.

Management

The aims of management in atopic disease may vary depending on the clinical context.

Management of symptomatic atopic disease

Allergen identification and avoidance

• with ingested allergens identification and avoidance are particularly important when atopic disease is associated with a food allergy, as this is the only means of therapy

• with inhalant allergens, methods have been evaluated to reduce exposure to indoor allergens, most importantly house dust mite (Box 13.1.2). A number of studies in sensitized individuals have demonstrated improvements in atopic dermatitis and allergic rhinitis following house dust mite reduction measures. The benefit of house dust mite avoidance in asthma is much more controversial

• other indoor allergens (cat, cockroach, mould) and outdoor allergens are less easily avoided and alternative forms of therapy may be required.

Symptomatic treatment

When allergen avoidance is difficult, the response is partial or the allergen cannot be identified, symptomatic treatment is indicated. A number of medications are available, including antihistamines, sympathomimetics, mast cell stabilizers, corticosteroids and leukotriene antagonists (Table 13.1.5).

Table 13.1.5 Medications for the symptomatic treatment of allergic disease

| Important mechanisms of action in allergic disease | Examples | |

|---|---|---|

| Antihistamines | ||

| First and second generation | H1-receptor antagonism | Diphenhydramine |

| Promethazine | ||

| Hydroxyzine | ||

| Second generation | Above plus antiallergic effects | Cetirizine |

| Decrease mediator release | Loratadine | |

| Decreased migration and activation of inflammatory cells | Terfenadine | |

| Reduced adhesion molecule expression | ||

| Sympathomimetics | ||

| β-agonists | Bronchial smooth muscle relaxation | Salbutamol |

| Reduce mast cell secretion | Albuterol | |

| Terbutaline | ||

| α- and β-agonists | Bronchial smooth muscle relaxation | Adrenaline (epinephrine) |

| Vasoconstriction – skin and gut | ||

| Inotropic and chronotropic effects | ||

| Reduce mast cell secretions | ||

| Glycogenolysis | ||

| Cromolyn | Mast cell stabilizer | Cromolyn sodium |

| Inhibits chemotaxis of eosinophils | Nedocromil sodium | |

| Inhibits pulmonary neuronal reflexes | ||

| Corticosteroids | Reduce T-cell cytokine production | Hydrocortisone |

| Reduce eosinophil adhesion, chemotaxis | Beclomethasone | |

| Reduce mast cell proliferation | Budesonide | |

| Reduce vascular permeability | Fluticasone/flunisolide | |

| Reverse adrenoreceptor downregulation | Triamcinolone acetonide | |

| Leukotriene antagonists | 5-Lipo-oxygenase enzyme inhibition, or LTD4 receptor antagonist | Montelukast |

LT, leukotriene.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree