19 Atopic Dermatitis

Clinical Presentation

Physical Examination

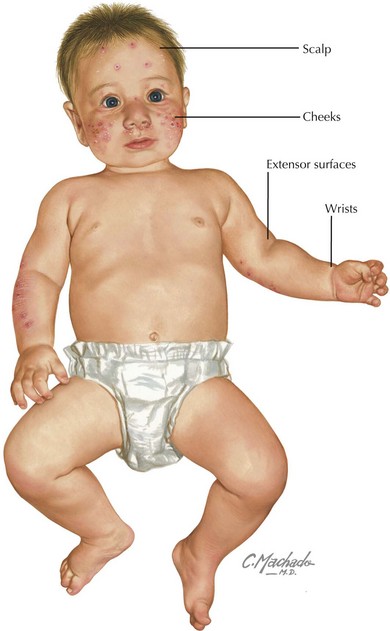

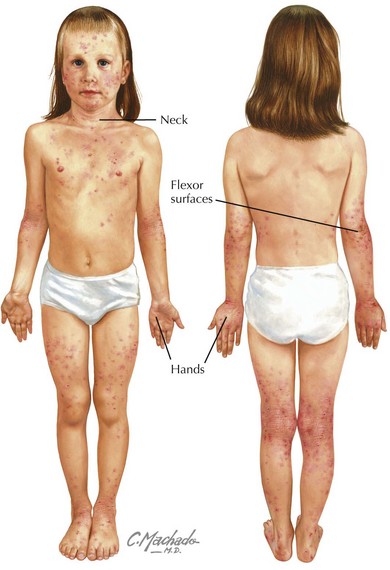

Physical examination of acute AD lesions reveals red papules and plaques that may also feature scaling, oozing, and crusting. In addition to acute lesions, children and adolescents with chronic AD may also have areas of thickened, dark skin (lichenification) at sites of prior acute lesions. The distribution of the rash is characteristic and varies by age. In infants, the cheeks, scalp, wrists, and extensor surfaces of the arms and legs are most affected (Figure 19-1). The diaper area is typically spared. The perioral and perinasal areas are rarely involved, leading to the characteristic “headlight sign” of pallor in these areas. In children and adolescents, the neck, hands, and flexor surfaces of the upper and lower extremities are more commonly affected (Figure 19-2).

Complications

Eczema Herpeticum

Secondary infection with herpes simplex virus (HSV) is a potentially life-threatening complication that may affect children with AD of all ages. Vesicular lesions typically appear in groups superimposed on areas of skin affected by AD between 2 days and 2 weeks after exposure to HSV-1 or HSV-2. The lesions evolve to appear as “punched-out” hemorrhagic lesions with crusting (Figure 19-3). Associated symptoms may include fever, fatigue, and lymphadenopathy. Diagnosis may be made by Tzanck prep, direct fluorescent antibody, polymerase chain reaction, or viral culture from swabs of the affected area.

Evaluation and Management

Laboratory Testing

There are no laboratory studies essential in the diagnosis of AD. If checked for other reasons, a white blood cell count with differential may reveal an eosinophilia; a serum IgE may be elevated. In severe or refractory cases of AD, an evaluation by a pediatric allergist with skin testing (see Figure 18-3) or IgE assays for specific allergens (also known as radioallergosorbent testing [RAST]) may aid in identifying triggers that should be avoided. RAST results should be interpreted with caution because the assays often have high false-positive rates, and in the case of food allergens, subsequent elimination of foods, such as milk or eggs, poses nutritional risks.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree