Introduction

Asthma is the most common and potentially serious respiratory illness encountered during pregnancy. Inflammation of the bronchial mucosa is currently thought to play a dominant role in the pathogenesis of increased bronchial airway obstruction and hyper-responsiveness. In the definition of asthma provided by the National Asthma Education Program, the three key components are: reversible airway obstruction, airway inflammation, and increased airway responsiveness to a variety of stimuli.

Asthma is not only the most common respiratory illness seen in pregnant women but also one of the most common medical illnesses encountered during pregnancy. The most recent estimates from national health surveys give an asthma prevalence of 3.7–8.4% in pregnant women and women of childbearing age in the United States. During the last decade a 29% higher worldwide prevalence has been seen, as well as a threefold increase in emergency room visits and hospital admissions. Also, a 31% higher mortality has been reported which, unfortunately, includes many young people. The increased prevalence involves urban more commonly than rural populations, with industrial pollution being quoted as a major factor. However, there are unexplained marked geographic variations possibly related to differences in genetic susceptibility.

Genetic predisposition plays a role as well, although no clear genetic pattern has yet been described. There is great interest in the population of the small island of Tristan da Cunha in the southern Atlantic Ocean. These people are thousands of miles from the stress and pollution of urban life but half of the population suffers from asthma. Two of the original settlers had asthma, and the gene or genes responsible for asthma susceptibility were passed down through the inbred generations. Scientists working on the human genome have collected samples from most of the island’s residents for clues to the genetic basis of asthma.

Effect of asthma on reproduction and pregnancy

Fertility

There is no evidence that fertility rates of women with asthma, eczema or hay fever are lower than those of women in the general population.

Menstrual cycle

The severity of asthma may show variations during the menstrual cycle, with premenstrual worsening being more common. It is speculated that estrogen and progesterone may modulate the smooth muscle adrenergic response to catecholamines.

Pregnancy

Pregnancy has not been observed to have a consistent effect on asthma, either worsening or improvement. This has led to the belief that the variability of its course during gestation may be related to the natural history of the disease rather than to the influence of pregnancy. Subsequent responses, however, tend to be similar to what happened during the first pregnancy. No particular trimester has been associated with worsening or improvement.

Nevertheless, some of the changes, either worsening or improvement, may actually be related to what some women do with their medications, without necessarily informing their doctors, when they realize they are pregnant. Some believe that the medications may be harmful to the fetus and stop taking them and therefore their asthma will get worse. These patients will be included in the group that “gets worse during pregnancy.” Others become more compliant when they realize that most medications are safe and that well-controlled asthma will provide better oxygen delivery to the fetus. These patients will be included in the group that “experienced improvement” during pregnancy.

Potential maternal complications include hyperemesis gravidarum, pre-eclampsia, vaginal hemorrhage, placental abruption, more complicated labors, higher rate of cesarean deliveries and depression. In addition, women with asthma account for up to 60% of pneumonia cases reported during pregnancy.

Possible fetal complications may include increased perinatal mortality, intrauterine growth retardation, preterm birth, low birthweight, and neonatal hypoxia. Studies show that women with severe asthma are at the highest risk, but when asthma is properly controlled there is little or no increased risk to mother or fetus. Patients should be made aware that most women with asthma can be managed effectively.

The diagnosis of asthma during pregnancy is usually not difficult provided that an adequate history and physical examination are performed. Most patients will have been diagnosed prior to pregnancy and will already be on some form of therapy. In a few, the diagnosis may not be obvious and a more detailed evaluation is needed. Pulmonary function studies are valuable and important to confirm the diagnosis. Occasionally, bronchospasm may be caused by a disease process other than asthma, such as acute left ventricular heart failure (“cardiac asthma”), pulmonary embolism, chronic bronchitis, carcinoid tumors, upper airway obstruction (e.g. laryngeal edema) or foreign bodies.

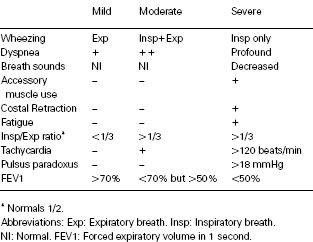

Common triggers of asthma include upper respiratory infections (more frequently viral), β-blockers, aspirin and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents, sulfites and other food preservatives, allergens (pollen, animal dander, etc.), smoking, gastric reflux, certain environmental factors (e.g. occupational asthma), and exercise or hyperventilation from other causes. Asthma is classified as mild, moderate or severe for diagnostic and therapeutic considerations (Tables 22.1, 22.2).

Table 22.1 Types of asthma

| Allergic (one-third of patients) | Idiosyncratic (two-thirds of patients) |

| Positive family history of asthma | Negative family history |

| Past history of allergiesa | No history of allergiesa |

| Elevated serum IgE | Normal serum IgE |

| Positive provocative tests | Negative provocative tests |

| a Rhinitis, urticaria, eczema. | |

Note: inhalation of an allergen leads to bronchospasm; intradermal injection of an allergen causes a wheal.

Table 22.2 Severity of asthma

The goals of therapy are directed toward the maintenance of normal or near normal pulmonary function, control of symptoms, maintenance of normal levels of activity, prevention of exacerbations and avoidance of medication side effects in order to give birth to a healthy baby. This can only be achieved if adequate oxygenation of the fetus is maintained.

Patient education is an extremely important aspect of the treatment of patients with asthma. Pregnant women are usually very receptive, thus providing an excellent opportunity for education in asthma management skills that they can continue to use after delivery.

However, there is a perception among a large segment of the lay population that all medications taken during pregnancy are harmful. Nevertheless, the risk of uncontrolled asthma is far greater, with potential maternal morbidity and hypoxemia in the fetus. Moreover, some women may have minimal clinical symptoms but their pulmonary function is abnormal enough to compromise fetal oxygenation. During an acute asthma attack, maternal oxygenation must be carefully monitored. A decrease in maternal PO2, particularly to below 60 mmHg, may result in marked fetal hypoxia. In addition, maternal hyperventilation and hypocarbia may result in decreased uterine blood flow. Fetal distress may occur even in the absence of maternal hypotension or hypoxia because compensatory mechanisms tend to maintain systemic arterial pressure and oxygenation in vital maternal organs at the expense of uterine blood flow. Fetal monitoring is essential during episodes of acute asthma exacerbation.

Objective measurements of lung function are preferable because the patient’s perception and the clinical signs of asthma severity are frequently inaccurate. Some patients may have minimal symptoms but their pulmonary function can be impaired enough to cause fetal hypoxia. Measuring the peak expiratory flow rate (PEFR) correlates well with the forced air expired in 1 second after a maximal inspiration (FEV1) and can be done with inexpensive, portable peak flow meters. They can be used at home to assess the course of asthma throughout the day, detect signs of early deterioration even before symptoms appear, and evaluate the response to therapy. In the hospital or at the office, a spirometer can be used for diagnosis or to more fully evaluate the severity of asthma.

Diet

Evidence is accumulating about the importance of some dietary factors in pregnant women with asthma and other allergic disorders. In 1998 the United Kingdom government recommended that women with a history of asthma, hay fever or eczema should avoid peanuts or products containing peanuts during pregnancy and breastfeeding because of the belief that allergy to peanuts may develop in utero. However, whether this advice has been beneficial is still uncertain. Adequate maternal intakes of fish (probably due to omega-3 content), apples, vitamin E, zinc and vitamin D have all been reported to be protective against the development of asthma and atopy in the offspring.

Exercise

Pregnant women with asthma should be able to continue their regular activities. Those on adequate treatment should be controlled well enough so that an attack is not provoked by exercise. For other women, exercise-induced asthma may be prevented by the inhalation of a β2-agonist or cromolyn sodium within an hour of beginning exercise. The beneficial effect lasts several hours.

Other factors

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree