This chapter deals with the investigations available to obstetricians to help assess the fetal condition. The techniques will be described under four headings:

1. GESTATIONAL AGE

ULTRASOUND

Routine Use:

Confirmation of ongoing intra-uterine pregnancy.

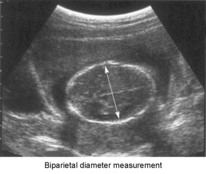

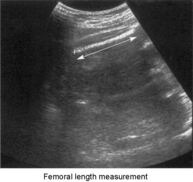

Assessment of gestational age (measurement of crown–rump length, biparietal diameter, femur length).

Identification of multiple pregnancy.

Recognition of major anomalies.

Specific Uses:

Threatened miscarriage (to confirm fetus is alive).

Antepartum haemorrhage (placental localisation).

Fetal growth studies (head–trunk ratio, estimated fetal weight, liquor volume, placental grade).

Assessment of high-risk cases (maternal disease, elevated serum alphafetoprotein, history of anomaly).

Postpartum (retained products).

Adjunct to Interventional Procedures:

Chorion villus sampling

Amniocentesis.

Fetal blood sampling (cordocentesis).

Intra-uterine therapy, e.g. intra-uterine transfusion.

Fetoscopy

Ultrasound in the estimation of gestational age

FETAL ABNORMALITY

2. IDENTIFICATION OF FETAL ABNORMALITY

SCREENING TESTS AND DIAGNOSTIC TESTS

A. Screening at 11 to 14 weeks

B. Screening at 15 to 21 weeks

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Assessment of the Fetus

1. Gestational age.

2. Identification of fetal abnormality.

3. Assessment of fetal growth.

4. Fetal wellbeing/functional maturity.

The traditional method of determining gestational age is from the date of the last menstrual period and clinical examination (see Chapter 5).

These methods may not be reliable:

1. LMP uncertain or forgotten.

2. Calculation depends on a ‘normal’ 28 day cycle.

3. The widespread use of hormonal contraception, oral and parenteral, makes ovulation unpredictable.

4. Uterine size may be difficult to determine, particularly in the patient who is obese or tense.

Ultrasound examination, pioneered by Donald in Glasgow in the late 1950s and early 1960s, has become the cornerstone of fetal assessment. Increased resolution and portability have led to the widespread use of ultrasound equipment from the earliest stages of pregnancy through to care during labour. Further, ultrasound is the only reliable technique which can be used in early pregnancy to identify both fetal viability and multiple pregnancy.

The contribution of ultrasound to obstetric practice is so great that it is useful to summarise the uses to which ultrasound may be applied:

Pelvic masses.

Measurement of the Crown–Rump Length of the fetus is the ideal before twelve weeks gestation.

Thereafter measurement of the fetal biparietal diameter, in conjunction with measurement of fetal long bones such as the femur, provides reasonable accuracy until the third trimester. The accuracy achieved depends on the observation that there is relatively little biological variation in these measurements in the first and second trimesters.

In other cases, termination may not be indicated but knowledge of the presence of the condition permits preparation of the woman, her partner and the paediatric and obstetric teams for treatment following delivery. A number of conditions may be amenable to fetal surgery but this expertise remains largely within a small number of highly specialised centres.

The term ‘prenatal diagnosis’ has become established to describe these diagnostic techniques.

It is important to distinguish between tests which are applied as screening tests and those which are diagnostic.

Screening tests are offered to a population in which there are no specific risk factors that would indicate the need for diagnostic testing. Thus a woman who had previously had a pregnancy complicated by fetal trisomy may elect to opt for diagnostic testing from the outset. The more sensitive and specific a screening test the closer it approximates a diagnostic test.

Screening for congenital abnormality may be undertaken using biochemical assays, ultrasound or both.

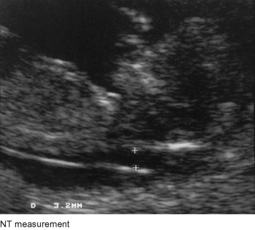

Ultrasound can be used at this stage to identify structural abnormalities. Anencephaly and anterior abdominal wall defects may be seen but more subtle signs are now used, the foremost of which is measurement of nuchal translucency. In normal first trimester pregnancy a fluid-filled area on the posterior surface of the neck may be seen and measured. An association between increased size of nuchal translucency (NT) and chromosomal and heart abnormalities is now well recognised. At any given maternal age the measurement of NT can be used to modify the underlying age-related risk of a fetal trisomy.

Detailed ultrasound assessment of fetal anatomy is commonly undertaken around 18 to 20 weeks gestation but at this stage ultrasound is not of value in identifying Down’s syndrome since nuchal translucency has disappeared at this stage (in the absence of associated abnormalities such as anterior abdominal wall defects such as exomphalos). Biochemical measurement of maternal serum alphafetoprotein (AFP), HCG and oestriol can be used, in conjunction with maternal age, to calculate a risk for Down’s syndrome, so-called triple testing. Again a high risk indicates the need for amniocentesis to obtain a fetal karyotype.

Measurement of AFP alone can be used as a screening test for a number of defects if detailed anatomy screening by ultrasound is not available. AFP is elevated in a number of conditions and, if elevated, indicates the need for further ultrasound assessment.