chapter 22 Assessing the Appropriate Role for Children in Health Decisions

The Traditional Role of Parents and Families

Evolving Understanding of Respectful Involvement of Children in Medical Decisions

The pediatrician must assess the following issues:

Assessing the Appropriate Role for Children in Health Decisions

The child’s capacity for communication

Issues

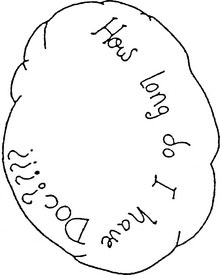

Conveying information to a child about medical interventions is a necessary step in determining the child’s understanding. But how much information is enough? As in communications with parents, you must impart difficult or complex information gradually. If the child’s threshold for understanding has been reached, more information might create anxiety and distress and should be withheld for the moment. Letting the child tell you how much he or she needs to know is an important strategy; it gives the child some sense of control of the situation. Figure 22–1 is the picture that a 12-year-old drew and used to ask a question that was too scary to verbalize.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree