chapter 3 Assessing Physical Growth and Nutrition

Measurements and Growth Charts

Recumbent length versus height

Because most babies younger than 10 to 12 months cannot stand alone and most toddlers refuse to stand still, any child younger than 2 years should be measured for length in the recumbent position. In children of this age group, recumbent length and standing height are not the same, the former being significantly greater. Standard growth charts for younger children are based on measurements of recumbent length. Various accurate measuring devices—some cheap, others more expensive—are available for determining recumbent length and height. The essential point is to use a stable, accurate, fixed device if both individual and serial measurements are to mean anything (Figs. 3-1 and 3-2). Accuracy is a must, but never more so than when there is the slightest concern about the child’s growth. To be absolutely sure, check all measurements at least twice, and never accept anyone else’s measurements as reliable.

Head circumference

The technique for measuring head circumference is described in Chapter 7. Be sure to check the measurement at least once to be certain it is accurate.

Large and Small Heads

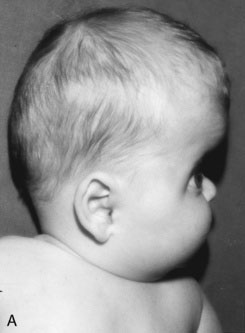

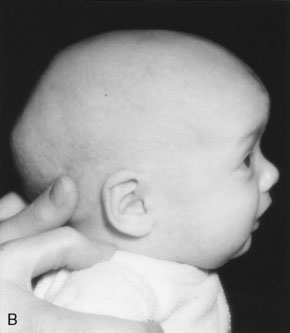

Remember that skull bones grow in a direction perpendicular to the suture lines. The directions in which the skull can and cannot grow after synostosis of a suture are therefore predictable, as is the shape of the resulting cranial distortion. For example, if the sagittal suture fuses prematurely, further lateral growth of the skull is prevented. Anteroposterior growth continues (perpendicular to the coronal sutures), and the skull will become long and narrow (a condition known as dolichocephaly) (Fig. 3-3).

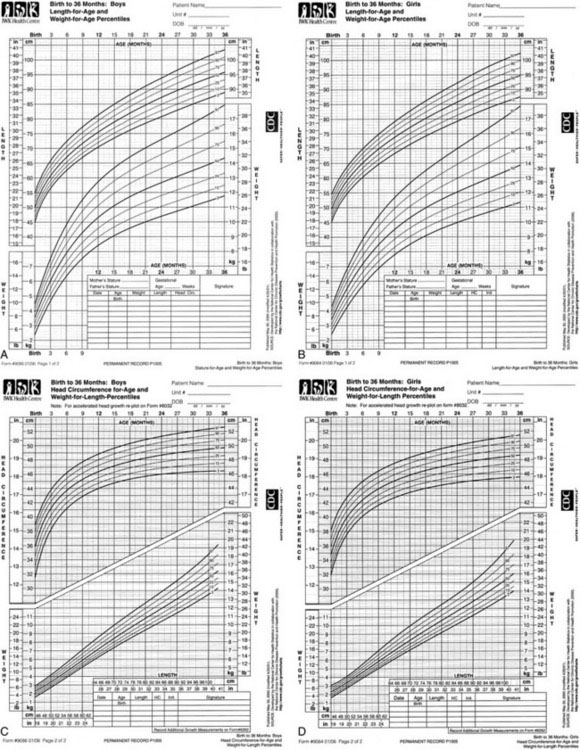

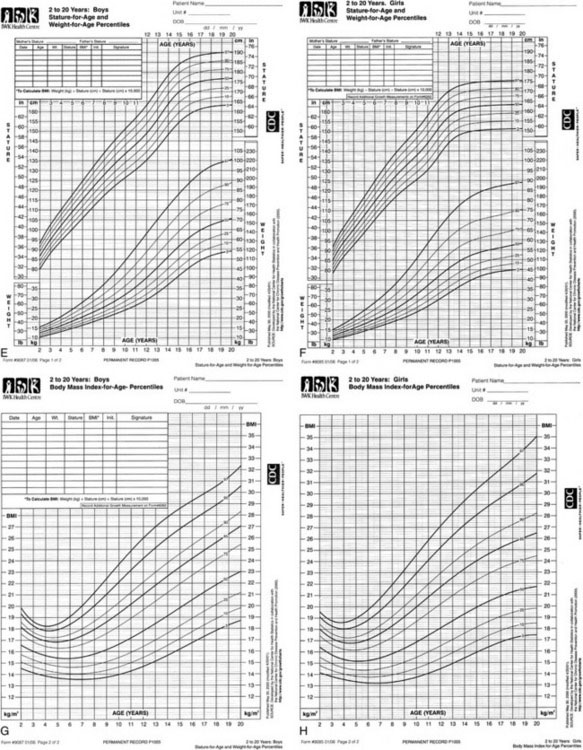

Graphic recording of measurements

The child’s recumbent length or standing height, body weight, and head circumference should be recorded and plotted on appropriate age- and sex-specific growth charts. In North America, the growth charts currently used almost universally are those published in 2000 by the National Center for Health Statistics in collaboration with the National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (Fig. 3-4). These charts permit plotting of length-for-age, weight-for-age, and head circumference–for-age measurements along percentile lines, as well as plotting of body mass index (BMI) on a percentile chart.*

FIGURE 3-4 Growth charts for children from birth to 20 years.

(Developed by the National Center for Health Statistics in collaboration with the National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, 2000; available at http://www.cdc.gov/growthcharts.)

BMI is determined using the following formula:

Mid-parental height

Special growth charts have been developed for children with certain dysmorphic conditions, including Down syndrome, Turner syndrome, and achondroplasia (see Recommended Reading).

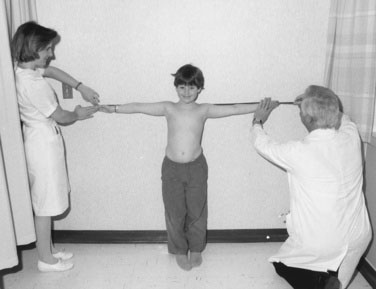

Arm span and its relationships

If a child is old enough to cooperate, you can measure the arm span by having the youngster stand with the back and heels touching the wall and the arms fully extended parallel to the floor, with the palms facing forward. With parental assistance and using a steel tape measure, measure the distance between the third fingers of each hand. The span-height difference and span-to-height ratio then can be determined (Fig. 3-5).

Measuring the upper and lower segments

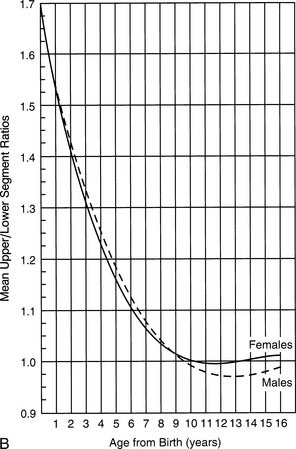

Measuring a child’s upper and lower segments is tricky and is not always supremely accurate. Obtaining these measurements requires identifying the top of the pubic ramus and marking it on the skin with a pen or wax pencil. This procedure sounds easier than it is, especially in a chubby youngster, in whom you must indent the adipose lower abdominal-suprapubic area to locate the top of the pubic bone. After you make the mark and release the pressure, the abdominal wall springs back and the mark does not always stay where you thought it was relative to the pubis. Make sure the youngster does not bend forward to look, because this movement can distort the measurement. Measure the lower segment by dropping a steel tape perpendicularly from the mark to the floor (Fig. 3-6, A). Then determine the length of the upper segment by subtracting the lower segment length from the height. Part B of Figure 3-6 shows the average upper-to-lower segment ratio at different ages. Remember that there are ethnic and familial differences in these ratios, so it is sometimes necessary to measure the parents as well.

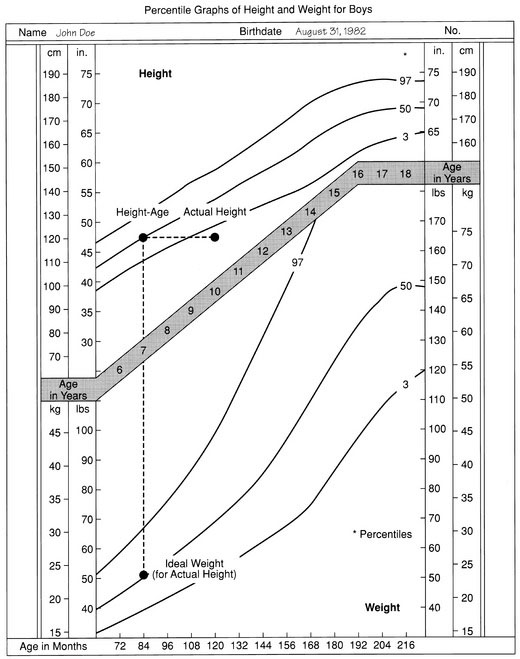

A Language for Communicating Information About Children’s Growth

Several ways of expressing growth measurements are more meaningful and useful. One is to determine the child’s “height-age” or “weight-age” (i.e., the age for which a particular measurement represents the 50th percentile on a standard growth chart) (Fig. 3-7). Figure 3-7 shows that the boy in question, whose chronologic age is 10 years 4 months, has a height-age of 7 years and a weight-age of 5 years 2 months. Stating each measurement in these terms immediately communicates the image of a child who is a little shorter than average but is also underweight or undernourished, even in relation to his reduced height.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree