21 Approach to the Child with Primary Immunodeficiency

Etiology and Pathogenesis

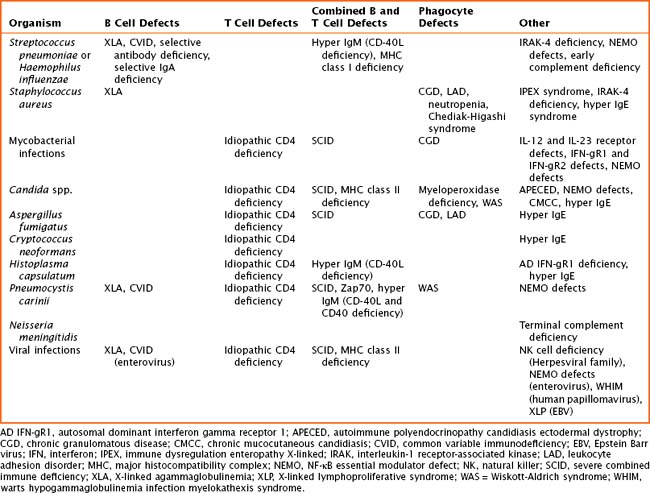

The pathogenesis of primary immune defects is related to the underlying cellular defect, which may be further divided into problems with the innate and adaptive immune system. Immune defects are distinguished by the cellular mechanism involved, including B cells and humoral or antibody defects, T cells and cell-mediated defects, combined B and T cell defects, phagocytic defects, complement defects, and newly described defects in pattern recognition molecules (Toll-like receptors [TLRs] and signaling molecules). The innate immune system is composed of phagocytes (dendritic cells, macrophages, and neutrophils), complement components, natural killer (NK) cells, TLRs, and signaling molecules. These cells are the first line of defense and respond to pathogens in a nonspecific manner. The adaptive immune system includes B cells, T cells, and combined defects. These cells recognize and respond to pathogens in a specific manner, leading to long-lasting immunity. There are also genetic disorders of immune regulation that cross both arms of the immune system. Specific disorders are often associated with particular infectious organisms (Table 21-1).

Disorders of the Innate Immune System

Complement

The complement system shares responsibility in host defense, induction of the adaptive immune system, inflammation, and clearance of apoptotic cells and immune complexes. The clinical manifestations of deficiencies early in the complement cascade are susceptibility to infections with Streptococcus pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenzae and rheumatologic abnormalities, such as systemic lupus erythematosus (see Chapter 29). Neisseria infections are more common with defects in later components of the complement cascade. Hereditary angioedema results from a defect in C1 esterase inhibitor enzyme function.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree