Chapter 50 Anemia

What Is Anemia?

Anemia is defined by a hemoglobin and/or hematocrit more than two standard deviations below the mean for age. Anemia is also classified according to red blood cell (RBC) size, as measured by mean corpuscular volume (MCV). Other RBC indices that may also be abnormal in anemia include mean corpuscular hemoglobin (MCH), a measure of the amount of hemoglobin in each RBC, and mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration (MCHC), a measure of the concentration of hemoglobin within each RBC. This chapter provides a general discussion of anemia. Chapter 63 discusses specific anemias.

How Do Hemoglobin and Red Blood Cell Size Change with Age?

The newborn’s hemoglobin varies with gestational age, timing of umbilical cord clamping, and clinical condition at the time of birth. Hemoglobin concentration is high at birth for a healthy term infant. It then decreases during the first 2 months, after which it slowly increases until adult levels are achieved during adolescence. RBCs also change in size with advancing age: At birth, RBCs are large, with MCV of 110 to 120 fl. MCV decreases over the first 6 months of life to 70 to 79 fl and then slowly rises to adult levels (80-95 fl) during late childhood and adolescence. Table 50-1 gives the age-associated ranges for expected hemoglobin and MCV. Values for MCH and MCHC are available in standard references.

Table 50-1 Age-Related Values for Hemoglobin and Mean Corpuscular Volume

| Age | Hemoglobin (g/dl) (± 2 SD) | Mean Corpuscular Volume (fl) (± 2 SD) |

|---|---|---|

| Newborn (full term) | 16.5 (3) | 108 (10) |

| 1 mo | 13.9 (3.2) | 101 (10) |

| 2 mo | 11.2 (1.8) | 95 (11) |

| 6–24 mo | 12.0 (1.5) | 78 (8) |

| 2–6 yr | 12.5 (1.0) | 81 (6) |

| 6–12 yr | 13.5 (2.0) | 86 (9) |

| 12–18 yr male | 14.5 (1.5) | 88 (10) |

| 12–18 yr female | 14.0 (2.0) | 90 (12) |

Adapted from Brunetti M, Cohen J: Hematology. In Robertson J, Shilkofski N: The Harriet Lane Handbook, ed 17, Philadelphia, 2005, Mosby, p 337.

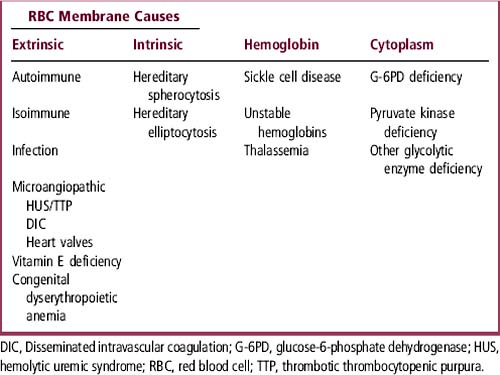

What Causes Anemia?

Anemia can be caused by RBC loss, destruction, or lack of production. The causes of anemia vary, based on the age of the child. Causes of anemia are discussed in the Evaluation section and listed in Tables 50-2 and 50-3.

Table 50-2 Anemia with Decreased Reticulocyte Index (RI < 2)

| Decreased MCV | Normal MCV | Increased MCV |

|---|---|---|

| Iron deficiency | Chronic infection | Vitamin B12 deficiency |

| Thalassemia | Recent blood loss | Folate deficiency |

| Lead (> 50 μg/dl) | Marrow failure | Metabolic disease |

| Copper deficiency | Malignancy | Chemotherapy |

| Chronic infection | Aplastic anemia | EtOH |

| Transient erythroblastopenia | Hypothyroidism | |

| Diamond-Blackfan syndrome | Myelodysplasia | |

| Renal failure (chronic) | Drugs |

EtOH, Ethanol; MCV, mean corpuscular volume.

EVALUATION

How Do I Detect Nutritional Anemia?

A careful assessment of the child’s diet is important in the evaluation of anemia. Iron deficiency is the most common nutritional anemia, so ask about sources of iron in the current diet (see Chapter 63). Also inquire about feeding during infancy: When was the child switched from breast-feeding or infant formula to cow milk, which is both a poor source of iron and a cause of gastrointestinal bleeding in infants younger than 12 months? Does the child drink goat milk, which is deficient in folic acid? Does the child take a strictly vegetarian diet, which is deficient in vitamin B12? Does the child currently take vitamins with or without iron? Does the child eat non-food items (pica), which suggests iron deficiency and increases the risk of lead intoxication?

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree