40 Advanced Heart Disease

In contrast to adults, severe advanced heart disease is a rare condition in children.1,2 There are two primary etiologies of pediatric heart failure: cardiomyopathy and congenital heart disease (CHD). The overall incidence of CHD is approximately 8 per 1000 live births,1 and the incidence of cardiomyopathy is estimated at 0.58 per 100,000 children.3,4 Yet only a fraction of children diagnosed with either form of pediatric heart disease eventually progresses to advanced heart disease5 necessitating long-term intensive medical management and/or recurrent hospitalization. Those that do are at high risk for developing end-stage heart disease,5,6 a clinical syndrome characterized by marked reduction in quality of life, functional status, nutritional deficiency, and respiratory distress. Similar to adults, however, the high mortality associated with pediatric advanced heart disease stems from its sequelae, including low cardiac output, respiratory failure, malignant arrhythmias, stroke, thromboembolism, multi-organ dysfunction, and infection.5 As such, children with advanced heart disease represent a diverse group ranging from those cared for at home by their parents and still participating in childhood activities to those in hospice care at the end of life. Regardless of the scenario, there is increasing evidence that advanced heart disease impacts not only the physical health of affected children, but also the psychosocial health and quality of life of the child and his or her family across the illness trajectory. Palliative care provides an opportunity to proactively address physical, psychosocial, and spiritual issues in order to maximize the quality of life children with advanced heart disease and their families, as well as prepare families for the complex end-of-life decision making.

Incidence and Epidemiology of Congenital Heart Disease and Pediatric Advanced Heart Disease

The reported prevalence of CHD varies widely, depending on the method of diagnosis and whether the data reflect prenatally detected CHD or live births of children with CHD. In general, the prevalence of CHD is approximately 3 per 1000 for clinically severe defects, 6 per 1000 when including the more moderate defects, and 9 to 20 per 1000 when including smaller septal defects and mild valve stenosis.1,2 CHD is the leading cause of infant deaths owing to congenital anomalies worldwide.1,2 Between 1940 and 2002, approximately 2 million infants were born with CHD in the United States.1 In those same six decades, enormous achievements in medical and surgical care of these infants and children have resulted in improved long-term survival. Despite dramatically improved short- and long-term outcomes, palliated advanced heart disease remains one of the leading causes of non-accidental death in childhood in the United States. During the past 60 years, surgical procedures have been developed to treat most congenital heart defects, including those that were historically uniformly fatal, such as hypoplastic left heart syndrome.7 During the same time period, major advances have been achieved in intensive care management, ventilatory support, mechanical support, intra-operative management, long-term medical management, and diagnostic imaging.7,8 These improvements are forcing reassessment of the outcomes and impact of CHD. For example, prenatal diagnosis has led to earlier detection, more controlled perinatal transition, and earlier surgical repair as well as more educated and prepared parents. The traditional statistics of prevalence and outcomes are, therefore of historic value, but may be less helpful in determining the longer term needs of children with advanced heart disease.

Improved survival rates of children with CHD is reported over the past two decades. A review9 of the multiple-cause mortality files compiled by the National Center for Health Statistics of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention from all death certificates filed in the United States found that from 1979 through 1997, mortality from heart defects for all ages declined 39 percent, from 2.5 to 1.5 per 100,000. In the last two years of the study, heart defects contributed to 5822 deaths per year. Of these deaths, 51% were infants and 7% were children 1 to 4 years old. In this series, age at death increased over the decade for every heart defect, as more palliated infants are surviving into adolescence and adulthood.9 Only a small number of children born with CHD will progress to advanced heart disease (Box 40-1). There are no published data on the numbers of children with CHD who meet criteria for advanced heart disease and prognostic indicators to assist with predicting which patients are likely to progress are limited.

Evolution of Palliative Care in Advanced Heart Disease in Children

Because of the previously described advances and improved longevity, pediatric cardiac teams now provide long-term care for children for whom previously the only treatment decision was the location of their death. Early efforts necessarily focused on survival. Over time, the focus expanded to include managing medical morbidity and maximizing the quality of life of children with CHD, including those with advanced heart disease. The evolution of palliative care in children with advanced heart disease has occurred slowly in part due to the perception of heart disease as treatable with the focus on surgical cures. This is similar to the evolution of care in adult advanced heart disease as well.10,11 It is important to recognize that many interactions between families and the healthcare team revolve around the surgical or interventional procedure to fix the child’s heart. Even in complex situations where palliative surgery is planned, death is rarely an immediate outcome. Aggressive, highly technological options and treatments are available and offered even in the final stages of advanced disease. Ongoing successes encourage caretakers and families to pursue continued therapies. Also, the progression of heart failure in children is largely variable, and the point at which there is no possibility for long-term survival is often unclear. Advanced heart disease is often marked by acute decompensations followed by periods of stability. This unpredictable nature often discourages end of life discussions for children and their families.

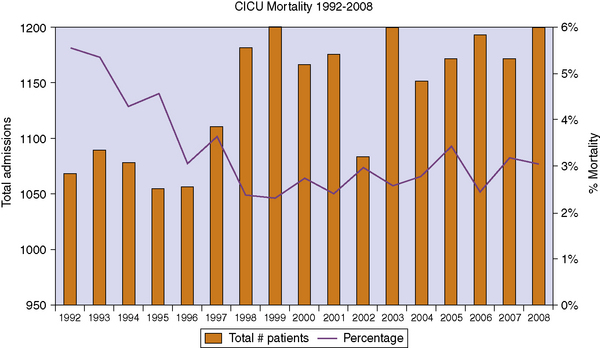

Because of the trajectory of acute decompensation alternating with periods of stability, many children with advanced heart disease die in the hospital, most often in an intensive care setting as advanced therapies are used even at the end of life. Little data are available for children with advanced heart disease. Fig. 40-1 shows the data from one large Cardiac Intensive Care Unit with approximately 1000 admissions per year. Overall, the ICU mortality is between 2% and 4% each year, which is approximately 30 to 40 deaths yearly. This percentage may vary between institutions and internationally. Although end of life discussions are happening with these families, there are limited data as to when and where these discussions are occurring.

Fig. 40-1 Overall mortality in a large pediatric cardiac intensive care unit.

(Data provided by the authors.)

Symptom management for children with advanced heart disease

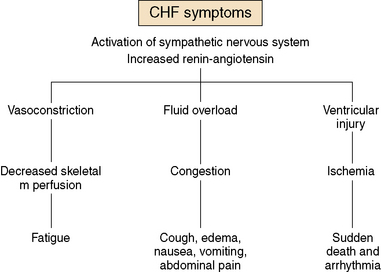

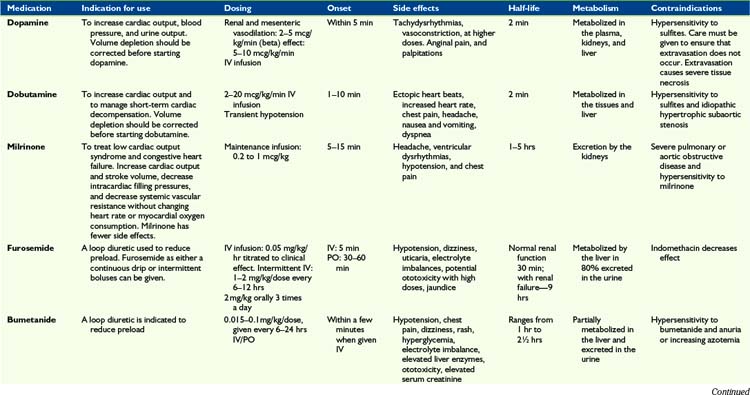

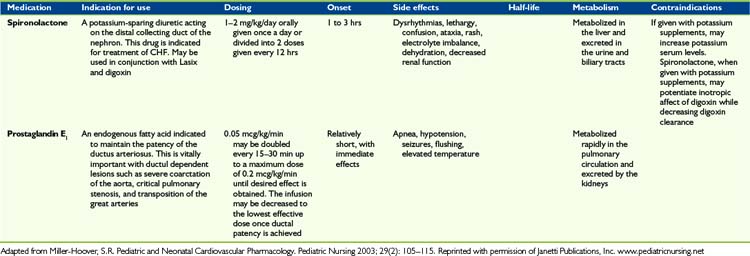

Children with advanced heart disease represent a diverse group with complex cardiac issues that result from either palliated complex CHD or from severe forms of cardiomyopathy or post-transplant care. Symptom management includes a variety of complex medical and psychosocial interventions in order to optimize quality of life. As cardiac function deteriorates, traditional symptoms of heart failure can ensue (Fig. 40-2). Symptom management can be complex and side effects of drugs can worsen symptoms. Some guidelines are offered in Table 40-1.

Fatigue

The activation of both the renin-angiotensin system and the sympathetic nervous system results in vasoconstriction and poor skeletal muscle perfusion. This often leads to overwhelming fatigue, sometimes out of proportion to the cardiac dysfunction. For patients in the early phases of advanced heart disease, fatigue can be particularly difficult to sort out, as it can often be confused with laziness or depression. Modified physical therapy and cardiac rehabilitation programs can be useful to avoid deconditioning and maintaining muscle tone. In addition, modified exercise programs have been shown to be beneficial to outlook and endurance in patients with CHD.12 For the more advanced heart disease patients, systemic vasodilators, such as milrinone, can help lower systemic vascular resistance and result in temporary improvement of fatigue. Many children and young adults describe “something lifting off my chest” after a few hours of a milronone infusion. There is some anecdotal evidence that a short infusion holiday of 3 to 5 days can have an improved effect lasting for several weeks. Some patients may benefit from this therapy either intermittently or as a continuous infusion.

Psychosocial health promotion for children with advanced heart disease

Because the trajectory of advanced heart disease is marked by episodes of acute decompensation alternating with periods of stability, children with advanced heart disease may be community dwelling and attending school, community dwelling, and unable to attend school, hospitalized, or in hospice care. Health promotion is necessarily individualized to each child. However, acknowledging this, awareness of the pervasive impact of CHD on the child and family is critical. Children with CHD may have long-term difficulties with physical growth, gross motor development, exercise capacity, behavioral abnormalities, psychiatric abnormalities, school performance, and quality of life.13 Parents may be dealing with both the uncertainty of their child’s illness and the stress of managing complicated feeding regimens, multiple medications, outpatient visits, and diagnostic procedures. Though evidence is limited, this may result in physical and mental health problems in parents or siblings, attenuated education for mothers, and a negative impact on parent employment.14,15

Psychosocial care for children with advanced heart disease and their families

As with any life-threatening chronic illness, CHD impacts the psychosocial health of affected children and families. The exact nature of the risk is difficult to pinpoint given the complexity of adaptation to chronic illness and inconsistencies in both research methods and findings. However, a body of research is emerging indicating that children with CHD may be at risk for a range of psychosocial issues, including behavioral problems, neurodevelopmental abnormalities, difficulty with social functioning, and psychiatric disorders.13,16 As healthcare team members evaluate children with CHD, each of these areas should be considered in order to identify areas for intervention to maximize the child’s quality of life.

Behavioral Problems

A systematic review of psychological adjustment of children with CHD described parental reports of behavioral difficulties ranging from 5% to 41% and at rates in excess of those occurring in normative samples or control groups.17 Both internalizing and externalizing problems are described in the literature.16–19 Further, school-age children who required surgery for CHD in the newborn period were 3 to 4 times more likely to achieve clinically significant scores for inattention and hyperactivity than normative samples.20 Disease severity was not significantly related to behavior problems in a recent meta-analysis.17 However, there is evidence that older age,17,19 deep hypothermic circulatory arrest, cyanosis, older age at repair, and multiple surgical procedures21 may be risk factors for long-term behavior problems. Despite the technological advances, behavioral outcomes of children repaired recently are not statistically different than those of children repaired in previous eras.22 Family characteristics have been associated with behavioral problems in children with CHD, including maternal worry and distress, maternal mental health, parenting style, and single parent household.17,23 Importantly, in a 2007 study,23 59% of the variance in behavioral outcomes was explained by parenting style, maternal worry, marital status, maternal mental health, and cyanotic status. Behavioral problems may affect many areas of quality of life, including family dynamics, school success, and social interactions, and are a key area for assessment and intervention when identified.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree