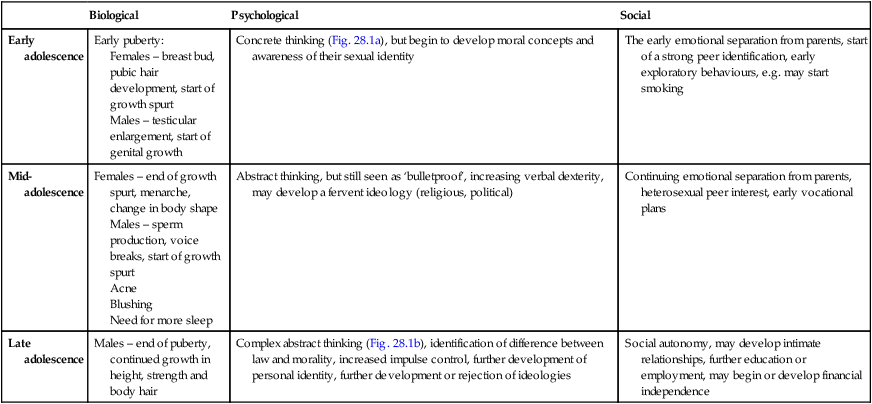

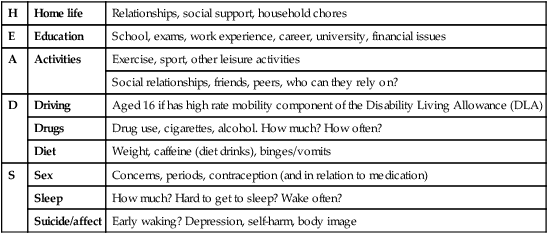

The transition from being a child to an adult involves many biological, psychological and social changes (Table 28.1). Pubertal development is considered in Chapter 11. Difficulties may arise if the pubertal changes are early or delayed. Table 28.1 Developmental changes of adolescence Adapted from Adolescent development. In: Viner R, ed. 2005. ABC of Adolescence. Blackwell, Oxford. Some practical points about communicating and working with adolescents are: • Make the adolescent the central person in the consultation. • Be yourself. When establishing rapport, it may be appropriate to engage the adolescent by talking about their interests, e.g. football, clothes or music, but do not try to be cool, false or patronising; your relationship should be as their doctor, not their friend. • Consider the family dynamics. Is the mother or father answering for the adolescent? Does the adolescent seem to want this or resent being interrupted? • Avoid being judgemental or lecturing. Avoid ‘You ….’ statements and use ‘I ….’ statements in preference, e.g. ‘I am concerned that you ….’. A frank and direct approach works best. Your role should be that of a knowledgeable, trusted adult from whom they can get advice if they so choose. • An authoritarian approach is likely to result in a rebellious stance. Working things out together in a practical way has the best chance of success. • Frame difficult questions so they are less threatening and judgemental, e.g. ‘Lots of teenagers drink alcohol, do any of your friends drink? How much do they drink in a week? Do you drink alcohol – how much do you drink compared to them?’ Likewise, when asking sensitive questions on, e.g. sexual health, always give young people warning and explain the rationale of why such questions need to be asked. • Confidentiality is particularly important to this age group and must be respected. Explain that you will keep everything you are told confidential, unless they or somebody else is at risk of serious harm. Always assess their understanding of confidentiality and correct any misunderstanding. • Bear in mind proxy presentations, e.g. abdominal pain, when the real reason is anxiety about the possibility of pregnancy, or sexually transmitted infection or the result of recreational drug use. • A full adolescent psychosocial history is useful to engage the young person, to assess the level of risk as well as provide information which will aid the formulation of effective interventions. The HEADS acronym may be helpful in this regard (Table 28.2), although questions must always be tailored to stage of development and the right of the young person to not answer should be respected. Table 28.2 HEADS acronym for psychosocial history taking in adolescents • Communicate and explain concepts appropriate to their cognitive development. For young adolescents, use concrete examples (‘here and now’) rather than abstract concepts (‘if … then’) . • History-taking should avoid making the assumption of heterosexuality with questions about romantic and sexual partners asked in a gender neutral way. • If they need to have a physical examination, consider their privacy and personal integrity – Who do they want present? As with any age, young people have the right to a chaperone but it should not be assumed the young person will want this to be their parent. Also, find out if they would prefer a doctor of the same sex, if this is an option. In the UK, young people can give consent if they are sufficiently informed and either over 16 years old or under 16 years and competent to make decisions for themselves. Conflict rarely arises about a treatment, as usually the adolescent, their parents and doctors agree that it is necessary. Handling of disagreement over consent is considered in Chapter 5. • Common acute illnesses: respiratory disorders, skin conditions, musculoskeletal problems including sports injuries and somatic complaints. Acute serious illness has become rare, with mortality predominantly from trauma • Chronic illness and disability: e.g. asthma, epilepsy, diabetes, cerebral palsy, juvenile idiopathic arthritis, sickle cell disease. The prevalence of some of the common chronic disorders in adolescence is shown in Table 28.3. There is also a range of uncommon disorders with serious chronic morbidity such as malignant disease and connective tissue disorders. In addition, children with many congenital disorders which often used to be fatal in childhood now survive into adolescence or adult life, e.g. cystic fibrosis, Duchenne muscular dystrophy, complex congenital heart disease, metabolic disorders, etc. Table 28.3 Prevalence of some chronic illnesses per 1000 adolescents (12–18 years old)

Adolescent medicine

Biological

Psychological

Social

Early adolescence

Early puberty:

Females – breast bud, pubic hair development, start of growth spurt

Males – testicular enlargement, start of genital growth

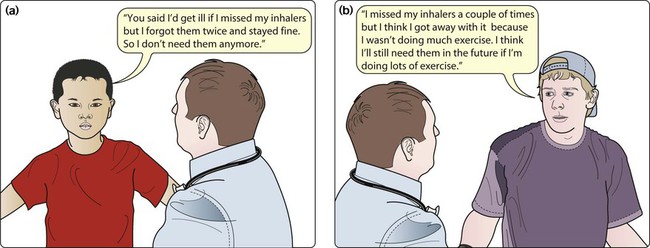

Concrete thinking (Fig. 28.1a), but begin to develop moral concepts and awareness of their sexual identity

The early emotional separation from parents, start of a strong peer identification, early exploratory behaviours, e.g. may start smoking

Mid-adolescence

Females – end of growth spurt, menarche, change in body shape

Males – sperm production, voice breaks, start of growth spurt

Acne

Blushing

Need for more sleep

Abstract thinking, but still seen as ‘bulletproof’, increasing verbal dexterity, may develop a fervent ideology (religious, political)

Continuing emotional separation from parents, heterosexual peer interest, early vocational plans

Late adolescence

Males – end of puberty, continued growth in height, strength and body hair

Complex abstract thinking (Fig. 28.1b), identification of difference between law and morality, increased impulse control, further development of personal identity, further development or rejection of ideologies

Social autonomy, may develop intimate relationships, further education or employment, may begin or develop financial independence

Communicating with adolescents

H

Home life

Relationships, social support, household chores

E

Education

School, exams, work experience, career, university, financial issues

A

Activities

Exercise, sport, other leisure activities

Social relationships, friends, peers, who can they rely on?

D

Driving

Aged 16 if has high rate mobility component of the Disability Living Allowance (DLA)

Drugs

Drug use, cigarettes, alcohol. How much? How often?

Diet

Weight, caffeine (diet drinks), binges/vomits

S

Sex

Concerns, periods, contraception (and in relation to medication)

Sleep

How much? Hard to get to sleep? Wake often?

Suicide/affect

Early waking? Depression, self-harm, body image

Consent and confidentiality

Consent

Range of health problems

Disease

Prevalence per 1000 adolescents

Musculoskeletal conditions

41

Skin conditions

32

Significant mental health problems

120

Diabetes

Type 1

2

Type 2

1–2

Respiratory conditions

150

Asthma

100

Cystic fibrosis

0.1

Epilepsy

4

Hearing problems

18

Cerebral palsy

1.5 ![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Adolescent medicine