43 Acyanotic Congenital Heart Disease

Shunt Lesions

Atrial Septal Defect

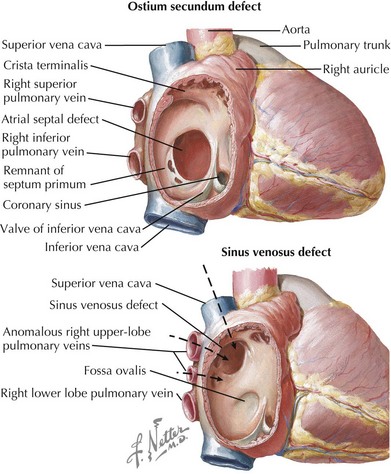

Atrial septal defects (ASDs) constitute 5% to 10% of all congenital heart defects and occur in approximately one in 1500 live births. There are five types of ASDs (Figure 43-1). The most common type is the ostium secundum ASD, which results from a deficiency in septum primum, the thin membrane-like septum that normally closes the foramen ovale. The second most common type is the ostium primum ASD, which is a defect in the canal septum. This septum normally divides the common atrioventricular (AV) canal and in so doing completes the anterior portion of the atrial septum and the posterior portion of the ventricular septum while dividing the common AV valve into the tricuspid and mitral valve. Defects in this septum result in AV canal defects, which are discussed later in this chapter. The third type is the sinus venosus defect, which is not a defect in atrial septum per se but rather a communication between the two atria by way of a “straddling” venous structure, either a pulmonary vein or a vena cava. It is frequently associated with partial anomalous drainage of the right-sided pulmonary veins connected to the superior vena cava (SVC). Coronary sinus ASDs are the fourth type and again are not true defects in the atrial septum but rather the physiologic consequence of a partially or completely unroofed coronary sinus with left atrial to right atrial drainage through the coronary sinus ostium. The fifth type of ASD is that seen with juxtaposition of the atrial appendages. This is extremely rare and results from an absence or misplacement of septum secundum, which normally closes the foramen ovale.

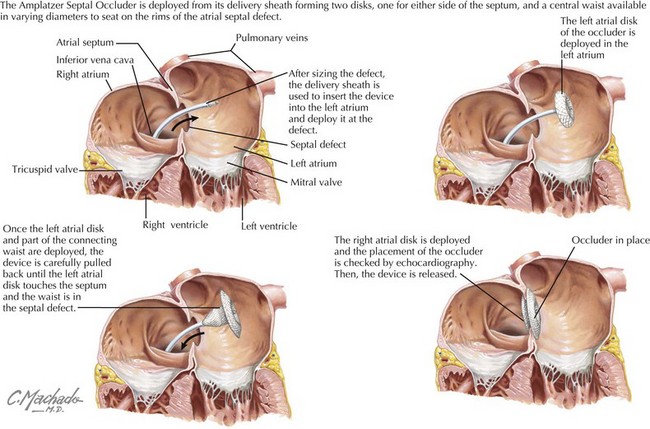

Ostium secundum defects may spontaneously close within the first 4 years of life, but the other types of ASDs usually do not. Options for repair include surgical closure or transcatheter device closure (Figure 43-2). Secundum defects with well-defined margins are the only type amenable to device closure. If left untreated into adulthood, ASDs can lead to pulmonary hypertension; exercise intolerance; atrial arrhythmias; increased risk of paradoxical embolus or stroke; and, late in life, to heart failure. Even when successfully closed in childhood, atrial arrhythmias may still occur decades later.

Ventricular Septal Defect

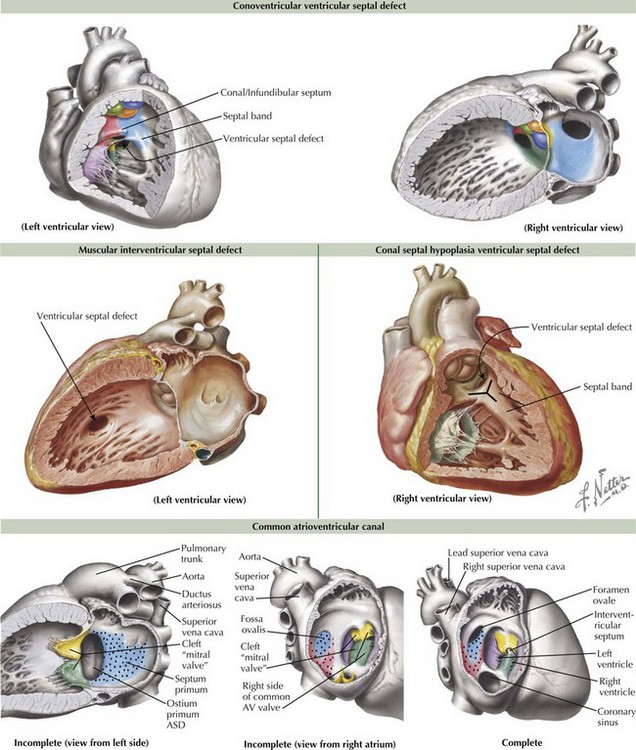

Ventricular septal defects (VSDs) account for about 20% of all congenital heart disease and occur in 2-10 of /1000 live births. The ventricular septum consists of the inlet (canal septum) posteriorly and inferiorly, running the full superoinferior length of the septal leaflet of the tricuspid valve; the infundibular, conal, or outlet septum superiorly, the muscular or trabecular septum; and the small, membranous septum at the junction of the other three (Figure 43-3). There are five types of VSDs that result from defects in or between these various components of the ventricular septum.

The most common type of VSDs are the conoventricular VSDs, which are defects between the conal or infundibular septum and the rest of the ventricular septum (see Figure 43-3). They may include the membranous septum, in which case they are a type of perimembranous VSD. These VSDs can be partially closed by tissue from the tricuspid valve, and many defects become smaller with time. Rarely, aortic regurgitation may occur because of prolapse of the right or noncoronary cusp into the VSD. Canal-type or inlet defects are usually seen in common AV canal defects (described more fully below) and occur from absence of the inlet septum; they extend along the full length of the AV valve. They may also be seen in straddling tricuspid valve and in some cases of transposition or double outlet right ventricle without AV valve abnormality. Malalignment and conal septal hypoplasia defects occur as a result of malalignment or absence of the conal or infundibular septum, respectively. Malalignment defects are seen in patients with tetralogy of Fallot (discussed in Chapter 44) and interrupted aortic arch along with other complex congenital lesions. Conal septal hypoplasia defects (see Figure 43-3) are sometimes referred to as subpulmonary or supracristal VSDs. They occur within the Y-shaped septal band beneath both semilunar valves and may be associated with prolapse of an aortic cusp resulting in aortic regurgitation. The second most common type of VSDs are called muscular VSDs, which are defects located anywhere other than those described above. These defects often spontaneously close if they are small to moderate in size (see Figure 43-3).

Common Atrioventricular Canal

A complete common AV canal consists of the above-mentioned septal deficiency, with the common AV valve suspended within the septal defect such that there is space proximal to the valve between the two atria (ostium primum ASD) and space distal to the valve between the two ventricles (canal-type VSD) (see Figure 43-3). An incomplete (or partial) AV canal has the same septal deficiency but has leaflet tissue dividing the valve orifice into two orifices and adhering to the crest of the ventricular septum such that there is no direct communication between ventricles. Thus, the entire septal defect, being proximal to the AV valve, is called an ostium primum ASD, and the morphology of the left side of the common AV valve is described as a cleft “mitral” because the two components of what should have formed the anterior leaflet of a mitral valve, remain separate or cleft. A transitional AV canal, similar to an incomplete canal, occurs when the AV valve attachments to the ventricular septum result in a restrictive VSD. The AV valve in this case also has two orifices. The primary defect in the canal septum remains the same, but the defects vary by degree of VSD closure by valve tissue.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree