at the top of a tower block, without the privilege of an enclosed garden or play space, has a difficult task.

By the age of 11, one in four children has experienced a serious accident.

By the age of 11, one in four children has experienced a serious accident. RESOURCE

RESOURCEPedestrian accidents are most common in the 5–9 age group when parents are falsely confident about their child’s skills: it is wiser to underestimate, rather than overestimate a child’s abilities. In general, children cannot cross a busy road safely, even at a traffic light, on their own until the age of 8 or 9 years, and cannot ride a bicycle safely on a main road until 13.

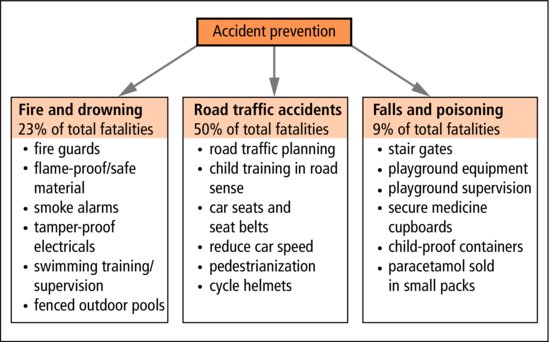

There is great need for better education of children and parents about safety, and for legislation to minimize the opportunities for accidents (Figure 15.1).

15.1.1 Head injury

KEY POINTS

KEY POINTS- Apparently trivial injuries can lead to intracranial bleeding that only becomes clinically apparent after an interval of time.

- Intracranial bleeding may occur without a skull fracture.

- CT head scan is the first-line investigation after significant head injury.

15.1.1.1 Management

- Airways, Breathing and Circulation

- Observe

- Pulse

- Respiratory rate

- Blood pressure

- Level of consciousness

- Pupillary size and reactions

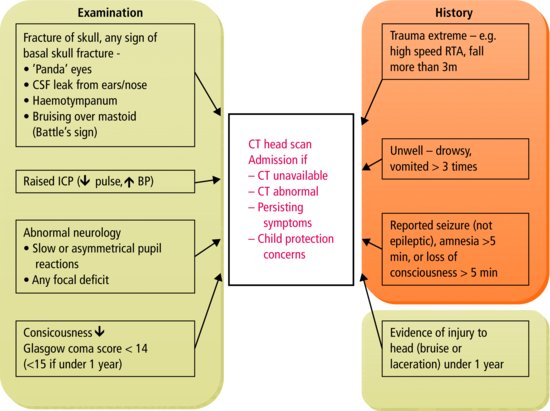

- CT head scan if risk factors for serious intracranial injury (Figure 15.2)

- Consider spinal imaging (X-rays +/− CT depending on suspicion and severity of injury)

- Pulse

- Admit and observe (usually overnight) if:

- Severe injury

- Any neurological symptom or sign including depressed conscious level

- Persisting symptoms:

- Headache

- Vomiting

- Altered behaviour

- Headache

- Severe injury

- Consider non-accidental injury if injuries and history don’t match, or other suggestive features (see Section 15.2).

Figure 15.2 Management of head injury. Use the Acronym ‘FRACTURE’ to remember when to do a CT Scan in a child with head injury.

RESOURCE

RESOURCE15.1.2 Burns and scalds

15.1.2.1 Scalds

- Caused by hot fluids

- Predominantly loss of epidermis

- Blistering

- Peeling.

The skin of young children sometimes suffers full thickness loss from comparatively minor scalds. There is a strong argument for limiting the maximum temperature of hot water in the home to 54 °C (129 °F). Most scalds occur in the kitchen.

15.1.2.2 Burns

- Caused by

- Direct contact with very hot objects

- Clothes catching fire

- Direct contact with very hot objects

- Often full thickness skin loss

- Shock – fluid is lost through the damaged skin surface (Figure 15.3).

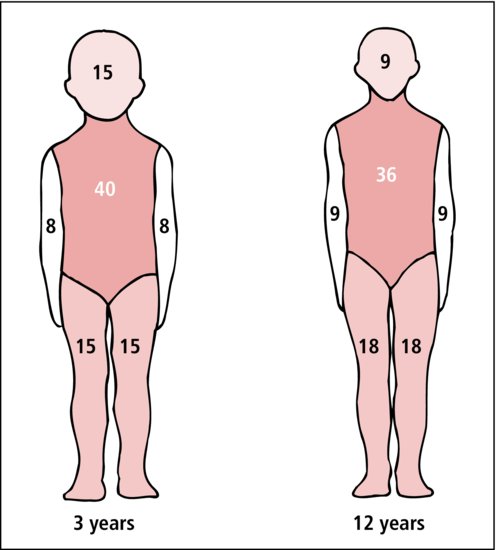

Figure 15.3 Skin surface areas at 3 and 12 years. The figures indicate the percentage of total body surface represented by each part.

If more than 10% of the body surface is involved, intravenous fluid therapy will be required. Burns involving 50% or more of the body surface carry a grave prognosis, although children have survived more extensive burns than this.

PRACTICE POINT

PRACTICE POINT15.1.2.3 Prevention

- Use cordless kettles or those with short coiled flexes (reduces risk of child reaching up and pulling the kettle over).

- Place pans on back of hob, handles turned inwards.

- Take care of children in the kitchen or use door gate to keep children away when cooking.

- Run cold water into bath before hot water.

- Use fireguards, radiator guards.

- Use smoke alarms.

15.1.3 Poisoning

15.1.3.1 Accidental poisoning (see Table 15.1)

Table 15.1 Substances children swallow accidentally

| Tablets and medicines* | Household and horticultural fluids | Berries and seeds |

| Sleeping tablets | Bleach | Laburnum |

| Tranquillizers | Turpentine | Deadly nightshade |

| Antidepressants | Paraffin | Toadstools |

| Iron | Cleaning fluids | |

| Analgesics | Weedkillers |

- Common

- Toddlers aged 2–4 years

- agile enough to find and swallow things

- do not appreciate the dangers

- agile enough to find and swallow things

- Less than 15% of children develop symptoms

- Death is very rare.

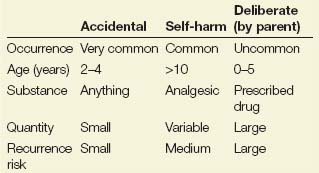

In the UK, things plucked from the hedgerows and ditches hardly ever cause serious illness. Occasionally younger children are given poisons by their parents (Table 15.2).

Table 15.2 Characteristic patterns in different types of poisoning

15.1.3.2 Deliberate poisoning

Older children may ingest drugs to self-harm, or recreationally (see Section 16.4.1), while rarely children may be deliberately poisoned by parents or carers (Table 15.1).

15.1.3.3 Management

TREATMENT

TREATMENT- Identify poison.

- Check with poisons information center.

- Estimate maximum amount/toxicity.

- Minimize absorption (? emesis, lavage, charcoal).

- Promote excretion (fluids/purgatives).

- Combat symptoms.

If a large amount of a potentially dangerous poison has been ingested in the previous 6 h, the stomach should be emptied. Emesis usually follows the administration of 20 mL of ipecacuanha syrup in orange juice, repeated if necessary. Gastric lavage may be needed if emesis does not occur, or if the child is unconscious.

Do not induce emesis if:

- The child is not fully conscious

- Caustics (bleaches, acids)

- (↑ risk of perforation)

- Hydrocarbons (turpentine)

- (↑ risk of pneumonitis).

Other measures:

Discourage absorption

- Dilute the poison

- Milk – usually available

- Absorbent agent

- Activated charcoal absorbs the poison

- Specific antidote (e.g. desferrioxamine chelates iron, thus reducing absorption).

Encourage excretion

- Purgatives

- Forced diuresis in selected cases (rare).

Admit poisoned children to hospital for observation for at least a few hours.

RESOURCE

RESOURCE- Toxbase (www.toxbase.org) – an online resource for the NHS – should be consulted for any poisoning.

- The National Poisons Information Service (www.npis.org) is available for more detailed expert help and advice. (Contact details are in the British National Formulary and the BNF for Children.)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree